Located on the 10th floor of an office and commercial building and in a space of just 47 square meters, Boundary Bookstore can be described as low-key. But it’s one of about a dozen independent book shops in Hong Kong that are testing the government’s limits on what can and cannot be read, in a city that is facing increasing political pressure and some would say an erosion of liberties.

Like similar bookshops that have opened in the past five years, it sells books that are becoming hard to find in Hong Kong, especially after the government began ridding public libraries of titles it deems as violating the national security law (NSL).

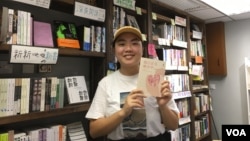

“Customers come here because they know what no longer exists in the libraries,” said Leanne Liu, a store manager.

Enacted by Beijing in 2020, the law penalizes secession, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign forces, with sentences as severe as life imprisonment.

The government credits the NSL with restoring order in the city, which saw months of large scale and sometimes violent protests in 2019 to stop a proposed bill that would’ve extradited suspects to mainland China for trial.

Critics say the law grants the government too much power. Since 2020, it has been removing books considered in violation of the law from libraries. According to local media, hundreds of titles have been taken off library shelves, including books about the anti-extradition protests, the June 4, 1989, crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrators in Beijing and even nonpolitical books written by Hong Kong’s democracy advocates or government critics.

Bookstores such as Boundary are stepping in to offer books that one wouldn’t find in libraries or even big chain bookstores, including one titled “Animal Farm Hong Kong.”

“I worry it’s more difficult for young people to know the truth,” said Liu, lamenting that some school libraries have already removed sensitive books. “It’s very obvious there are fewer sensitive books being sold at major bookstores as well.”

Equally committed to protecting Hong Kong residents’ freedom to read and write what they wish — are the city’s dozen or so independent publishers — which continue to publish works that may be considered sensitive by the government.

Daniel Wong, whose publishing company’s name translates to “A Kind of Culture,” publishes books about the 2019 protests. He was disqualified from exhibiting at the annual Hong Kong Book Fair last year, but that hasn’t stopped him from continuing to publish. The company will soon release a book whose Chinese name means “HongKongers - The Story of Our Exodus,” based on interviews of more than 100 Hong Kong people who have emigrated abroad.

“There’s no need to worry. I see different books coming out; different books can still be sold,” Wong said.

Hong Kong’s chief executive, John Lee, has assured the public that it can still buy books the government doesn’t see fit to be stocked in public libraries.

That has led Wong and others to assert that just because a book is pulled from the libraries doesn’t mean it’s been banned.

“We’re trying to not step on the (red) line. It’s a matter of trial and error because we don’t know where the line is,” he said.

Leslie Ng, chief editor of another publishing house, Bbluesky, said many of the independent publishing houses were opened by young people in the past two years partly because of a desire to maintain Hong Kong’s character after the 2019 anti-extradition protests and passage of the new law.

He agrees that there’s no need to self-censor.

“If Hong Kong’s government wants to take down books from library shelves, we have no say over this, but we are disappointed because Hong Kong has all along been a free place in Chinese society,” Ng said. “Whether we like it or not, we all know this is the reality. What we can do is sell books that are off library shelves.”

Book publishers and sellers have offered a sort of sanctuary for Hong Kong people yearning to read different perspectives at a time when some feel self-censorship has grown more prevalent in mainstream media.

“Since 2019, I’ve been buying more books,” said Faye, an office worker picking up an order from Boundary. “As long as I can buy these books, I will buy them. I’m afraid I won’t be able to buy them one day.”

She declined to reveal her full name, to avoid problems.

Some bookstores have also become popular community gathering places for those who want to connect with others trying to cope with the changes in Hong Kong, according to local media.

Bookshops and publishers are walking a tightrope. They say they don’t know where the red line is because the government doesn’t clearly define what type of content violates the security law.

“Some bookstores are afraid to buy sensitive books. For instance, there was a book by an independent journalist reflecting on her experience covering the anti-extradition bill protests, but no one bought it. It contained the eight-word protest slogan that the government finds objectionable,” Wong said.

He noted that there’s always a risk that after a book is published, the government will find it unacceptable.

As for Boundary and other bookstores like it, they are shying away from selling books written by former newspaper publisher Jimmy Lai and activist Joshua Wong, both of whom are in jail on NSL-related charges. Their books have also been banned from libraries.

So far, Boundary hasn’t been inspected by authorities because of NSL, but another bookstore is paid frequent visits by the fire department and police for supposed possible building code violations, Liu said.

“I don’t know how long we can exist. We will continue to sell books as long as possible,” Liu said.