When Americans talk about the “holiday season,” it’s understood that this includes the Christian Christmas, the Jewish Hanukkah, and the secular New Year’s Day.

But 45 years ago, a weeklong celebration joined the parade when the African-American holiday of Kwanzaa was observed for the first time.

Kwanzaa begins the day after Christmas, and celebrates African culture. The word "Kwanzaa" comes from a phrase that means "first fruits" in the Swahili language, and the observance is based in part on the harvest celebrations of ancient Africa.

The seven-day festival was developed in its modern form during the black-nationalist movement of the 1960s by Maulana Karenga, an African-American scholar and activist. At first he called Kwanzaa an “alternative” to Christmas, which, he said, was a white-people’s holiday.

But it soon became a mainstream celebration of family, community, and black Americans’ African roots.

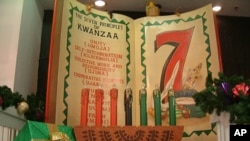

Kwanzaa festivities include stories, poetry, music, feasting and gift-giving. A candle is lit on each of the festival's nights to represent seven traditional values of African culture. Those principles are unity, self-determination, collective work and responsibility, cooperative economics, purpose, creativity, and faith.

Kwanzaa symbols include a decorative mat on which other items are placed. They often include corn, representing the harvest; a candelabra called a “kinara,” holding seven candles; a communal cup; gifts; a poster of the seven principles; and a black, red, and green Pan-African flag.

Kwanzaa begins on Dec. 26, the day after Christmas, and ends on New Year's Day. Many American communities now include it in their recognition of the holidays of the season.