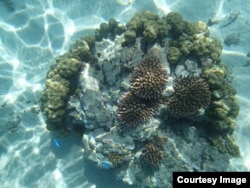

A new study on heat-tolerant corals that may lead to new ways of conserving reefs in a warmer world.

Coral reefs are home to about one-third of everything that lives in the ocean.

Reefs help protect coasts from storm damage and provide food and jobs for some one billion people. But rising ocean temperatures and increasing acidity are killing them at a rapid pace.

As much as 80 percent of the corals in the Caribbean are dead, as are nearly 75 percent of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, the largest reef on the planet.

A research team led by marine biologist Stephen Palumbi of Stanford University, compared a single coral species living in two adjacent ponds in a remote Pacific Island lagoon in Samoa. One pool reached 35 degrees Celsius, a higher temperature than most corals can withstand. The other was a few degrees cooler.

Palumbi's team transplanted corals from the cooler pool to warmer waters to see how they would respond.

“The simple question was, can an individual acquire the ability to live in warmer water?" Palumbi said. "Can it acquire heat tolerance? Or is the ability to live in that water just due to the genes, just innate to the corals that are living there.”

After about a year, the cool pond transplants were tested in a laboratory heat stress tank. The findings, reported in Science, show that although the corals were only about half as heat-tolerant as corals that had been living in the warmer pool all along, they adjusted quickly compared to how the creatures would naturally evolve over time.

“We estimate that it would take about 50 to 100 years for evolution to generate this kind of change, mostly because corals are very long-lived animals and the generation time is quite long," he said. "So evolution works fairly slowly in those cases, whereas the physiology seems to react very quickly to changes in the local environment and then buffer these individual corals against heat stress.”

The coral species native to the warmer part of the reef had a double advantage.

“They had the genes to be able to live there," Palumbi said. "And they also had the physiology to be able to adjust to it. The corals from the cool pool had the physiology too, but they didn’t have the warm water genes."

The study suggests that as the ocean warms, some corals can adapt but not, he fears, at the same pace that the planet is heating up.

“But this ability to respond physiologically and evolutionarily might give them a few extra decades, might give them a little extra time to adjust to climate change," he said. "It gives us a little extra time to fix the problem.”

The study results, Palumbi says, could encourage decision-makers to set conservation priorities to protect reefs with heat-tolerant corals. He adds that as ocean temperatures rise, these more resilient corals could help restore damaged reefs.

Coral reefs are home to about one-third of everything that lives in the ocean.

Reefs help protect coasts from storm damage and provide food and jobs for some one billion people. But rising ocean temperatures and increasing acidity are killing them at a rapid pace.

As much as 80 percent of the corals in the Caribbean are dead, as are nearly 75 percent of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, the largest reef on the planet.

A research team led by marine biologist Stephen Palumbi of Stanford University, compared a single coral species living in two adjacent ponds in a remote Pacific Island lagoon in Samoa. One pool reached 35 degrees Celsius, a higher temperature than most corals can withstand. The other was a few degrees cooler.

Palumbi's team transplanted corals from the cooler pool to warmer waters to see how they would respond.

“The simple question was, can an individual acquire the ability to live in warmer water?" Palumbi said. "Can it acquire heat tolerance? Or is the ability to live in that water just due to the genes, just innate to the corals that are living there.”

After about a year, the cool pond transplants were tested in a laboratory heat stress tank. The findings, reported in Science, show that although the corals were only about half as heat-tolerant as corals that had been living in the warmer pool all along, they adjusted quickly compared to how the creatures would naturally evolve over time.

“We estimate that it would take about 50 to 100 years for evolution to generate this kind of change, mostly because corals are very long-lived animals and the generation time is quite long," he said. "So evolution works fairly slowly in those cases, whereas the physiology seems to react very quickly to changes in the local environment and then buffer these individual corals against heat stress.”

The coral species native to the warmer part of the reef had a double advantage.

“They had the genes to be able to live there," Palumbi said. "And they also had the physiology to be able to adjust to it. The corals from the cool pool had the physiology too, but they didn’t have the warm water genes."

The study suggests that as the ocean warms, some corals can adapt but not, he fears, at the same pace that the planet is heating up.

“But this ability to respond physiologically and evolutionarily might give them a few extra decades, might give them a little extra time to adjust to climate change," he said. "It gives us a little extra time to fix the problem.”

The study results, Palumbi says, could encourage decision-makers to set conservation priorities to protect reefs with heat-tolerant corals. He adds that as ocean temperatures rise, these more resilient corals could help restore damaged reefs.