New scientific evidence suggests what or how much we eat isn’t the only factor affecting our weight. The microbes living in our intestines matter, too.

The results of this new study raise the possibility that probiotic bacteria may someday be added to diet and exercise to help fight obesity.

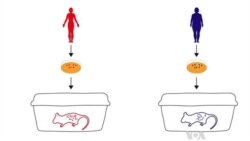

In the study, cited in Science, researchers started with mice raised in sterile environments with no bacteria in their guts and gave them gut microbe samples taken from human twins, both identical and fraternal. The twins’ genes were similar, but one of each pair was obese, the other was not.

Mice that received gut bacteria from the obese twin gained more weight than those inoculated with the thin twin microbes, and their metabolisms showed signs of trouble like those seen in obese humans.

“That was a surprise,” said Ronald Evans, a molecular biologist at the Salk Institute.

Evans was not involved in this research, but wrote a commentary on two related studies published last week in Nature.

The studies showed people with less diverse collections of microbes in their guts are more likely to gain weight, and show the beginning signs of diabetes, than those with more microbial diversity.

“The question [those studies] left on the table is, is the microbiome following the changes in our bodies,” he said, “or is it causing the changes in our bodies?”

He says the latest study takes an important step toward saying the microbes cause the changes.

But things really got interesting when the researchers put the obese-microbe mice and the lean-microbe mice in the same cage.

“Co-housing resulted in the invasion of the lean microbes into the obese cage mate’s gut community, but not vice versa,” said Washington University scientist Jeffrey Gordon, who coordinated the research.

When those lean microbes invaded and took over the guts of the obese-microbe mice, those mice gained less weight than mice that didn’t have a cage mate carrying lean microbes.

But it didn’t happen the other way around: having a fat cage mate didn’t make the lean-microbe mice fat.

But before anyone goes out to find a skinny roommate to help lose weight, consider that the mice swapped microbes through the unsavory habit of eating each other’s droppings.

“The question is, can we do this in people,” said Evans, the Salk Institute researcher, “and can we actually get to the point where we have a culture that would be what you might call a good bacteria, or probiotic pill?”

Gordon and his colleagues have cultured some of the microbes from the lean mice, but the cultures were less effective.

And for now, at least, it’s not possible to take a magic probiotic pill and eat all the hamburgers you want. Mice that ate a high-fat, low-vegetable diet gained weight regardless of what microbes they carried, though lean-microbe mice gained less weight. And this time the lean microbes didn’t take over the guts of obese-microbe mice.

“The answer appears to be diet, diet, diet,” Gordon said.

Better diets improved the diversity of microbes in overweight people’s guts in the two studies in Nature on which Evans commented, and reduced the metabolic symptoms that can lead to disease.

Except, unfortunately, in those people who already had diverse gut microbes. They didn’t get the same benefit from changing diets.

“When we dine, we don’t dine alone,” Evans said. “We are dining with all of our microbial friends that we’re carrying around with us.”

And there’s growing evidence that the 100 trillion or so microbes we carry on us and inside us - what scientists call our microbiome - are doing all sorts of things we never expected, from training our immune systems to regulating our moods.

Good reasons to treat them right, Evans says.

“You want to be nice to your microbiome. It could be our friend.”

The results of this new study raise the possibility that probiotic bacteria may someday be added to diet and exercise to help fight obesity.

In the study, cited in Science, researchers started with mice raised in sterile environments with no bacteria in their guts and gave them gut microbe samples taken from human twins, both identical and fraternal. The twins’ genes were similar, but one of each pair was obese, the other was not.

Mice that received gut bacteria from the obese twin gained more weight than those inoculated with the thin twin microbes, and their metabolisms showed signs of trouble like those seen in obese humans.

“That was a surprise,” said Ronald Evans, a molecular biologist at the Salk Institute.

Evans was not involved in this research, but wrote a commentary on two related studies published last week in Nature.

The studies showed people with less diverse collections of microbes in their guts are more likely to gain weight, and show the beginning signs of diabetes, than those with more microbial diversity.

“The question [those studies] left on the table is, is the microbiome following the changes in our bodies,” he said, “or is it causing the changes in our bodies?”

He says the latest study takes an important step toward saying the microbes cause the changes.

But things really got interesting when the researchers put the obese-microbe mice and the lean-microbe mice in the same cage.

“Co-housing resulted in the invasion of the lean microbes into the obese cage mate’s gut community, but not vice versa,” said Washington University scientist Jeffrey Gordon, who coordinated the research.

When those lean microbes invaded and took over the guts of the obese-microbe mice, those mice gained less weight than mice that didn’t have a cage mate carrying lean microbes.

But it didn’t happen the other way around: having a fat cage mate didn’t make the lean-microbe mice fat.

But before anyone goes out to find a skinny roommate to help lose weight, consider that the mice swapped microbes through the unsavory habit of eating each other’s droppings.

“The question is, can we do this in people,” said Evans, the Salk Institute researcher, “and can we actually get to the point where we have a culture that would be what you might call a good bacteria, or probiotic pill?”

Gordon and his colleagues have cultured some of the microbes from the lean mice, but the cultures were less effective.

And for now, at least, it’s not possible to take a magic probiotic pill and eat all the hamburgers you want. Mice that ate a high-fat, low-vegetable diet gained weight regardless of what microbes they carried, though lean-microbe mice gained less weight. And this time the lean microbes didn’t take over the guts of obese-microbe mice.

“The answer appears to be diet, diet, diet,” Gordon said.

Better diets improved the diversity of microbes in overweight people’s guts in the two studies in Nature on which Evans commented, and reduced the metabolic symptoms that can lead to disease.

Except, unfortunately, in those people who already had diverse gut microbes. They didn’t get the same benefit from changing diets.

“When we dine, we don’t dine alone,” Evans said. “We are dining with all of our microbial friends that we’re carrying around with us.”

And there’s growing evidence that the 100 trillion or so microbes we carry on us and inside us - what scientists call our microbiome - are doing all sorts of things we never expected, from training our immune systems to regulating our moods.

Good reasons to treat them right, Evans says.

“You want to be nice to your microbiome. It could be our friend.”