The Gulf of Mexico oil disaster comes during spring spawning season, an especially bad time for aquatic life making them extraordinarily vulnerable to the toxic effects of the oil itself, says Doug Rader, chief oceans scientist for the Environmental Defense Fund.

"Now the same thing is happening with birdlife migrating to and from the tropics. Those that have completed their migrations in the Gulf region are nesting and are beginning to feed this year's crop of migratory birds."

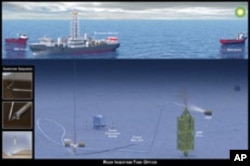

As the oil gushes from the broken well head at the sea floor, Rader says it has the potential to contaminate each layer of the water column that, "directly exposes those animals to toxicity, at the surface including the very sensitive surface zones where not only sea turtles and marine mammals and sea birds can be oiled, but also where the highways for fish larvae exist. And then as it rains back into the abyss over a much wider area carrying toxicants back into the deep sea where ancient corals and other sensitive ecosystems exist."

Limited choices

One response strategy has been to use dispersants or anti-freeze-like chemicals to break the oil up into smaller globules.

Those particles mix more readily with water, and sink. Rader says dispersants are being sprayed from airplanes and - for the first time - pumped directly into the deep ocean unsure of its effects.

It is a choice, he says, between two bad options. While the chemicals may protect birds and other wildlife by dissipating the slick before it reaches shore, their toxicity in the Gulf could harm fish and other marine life.

Judith Dowell, a biologist with Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and an expert on oil spill contamination, says it is important to understand the nature of the oil in order to predict its ecological effects.

"If a lot of it is very light material, it is going to vaporize. If a lot of it is heavy material, it may precipitate to the bottom. In the meantime, you have these medium molecular weight compounds that are dispersing within the water column. Until you can get some very accurate measurements of the depth of the slick and the geographical extent of the slick, it's not easy to do."

Widening threat

The slick threatens sensitive coastal wetlands, areas critical to wildlife.

Barrier islands and wetlands also serve to buffer towns on the coast from hurricanes and storm surges. Doug Rader with the Environmental Defense Fund says the spill may finally force coastal communities to put more adequate plans and safeguards in place to prevent an off shore disaster in the future.

"There are thousands of wells in the Gulf. There are 35,000 miles [56,000 kilometers] of pipeline in the Gulf," says Rader. "It is pretty clear that the status quo in terms of investment to prevent risk and to respond to events wasn't adequate and that some retrofitting of that entire infrastructure is necessary to be able to sustain the current level of production in the Gulf."

Rethinking offshore drilling?

Rader says the time is also ripe to rethink the wisdom of offshore drilling in favor of other energy options in the face of climate change.

"That going forward with a more balanced portfolio of energy sources that begins to address the global problem of warming caused by greenhouse gas emissions and threatening coastal areas like coastal Louisiana by rising seas and intensifying storms has to be a piece of the mix."

To this end, on May 12, Senators John Kerry and Joe Lieberman introduced long-awaited climate and energy legislation.

The bill covers a broad cross-section of the nation's top environmental and energy issues, from expanded nuclear power and carbon capture and sequestration, to giving states veto power over drilling within 120 kilometers off shore if, in the language of the proposed law, "they stand to suffer significant adverse impacts in the event of an accident."