For sheer drama and poignancy, real life stories sometimes outshine fiction. Consider the case of piano virtuoso Leon Fleisher. In 1966, at the height of a phenomenal international career, a medical condition called "focal dystonia" cost him the use of his right hand.

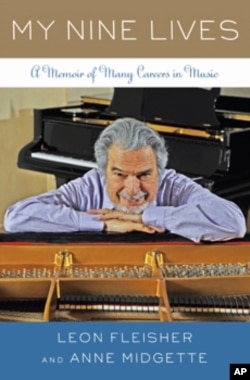

Fleisher retired from performing, going on to teach many of today's great pianists. But as his new memoir "My Nine Lives" and his CD, "Journeys" make clear, Fleisher has made a remarkable comeback, returning - with two hands - to full creative form.

Prodigy

Born in 1928 in San Francisco, Leon Fleisher was first introduced to the piano at the age of four. Although he was soon recognized as a prodigy, he says his first sense of the true depths of music came when his parents gave him a recording of Brahms' Piano Concerto #1 in D Minor.

"It is absolutely hair-raising how Brahms shakes his fist at the heavens and this Olympian, this imperious music would rise over this timpani which is thundering in the background," says Fleisher. "It's stormy music. It's unbelievable."

At the age of nine, Fleisher became a protégé of the legendary piano virtuoso and composer Artur Schnabel Schnabel traced his own pianistic lineage through his teachers back to Beethoven. Fleisher recalls that Schnabel's classes were filled with inspiring and memorable moments. He remembers Schnabel's coaching him about Beethoven's complex Piano Sonata #3 Opus 109.

"It's a gorgeous work full of pastoral harmonies. But suddenly, the key changes, and a sort of poignant nothingness intervenes," says Fleisher. "Schnabel said at that moment 'It has to feel like a deathly stare.' That's a picture. That's only remained with me for about what, 70 years?"

Tempered glory

Those 70 years have brought tragedy as well as glory. After a New York Philharmonic Orchestra debut in 1944 at the age of 16, Fleisher went on to a dazzling career on the world stage. In 1966, Fleisher was at the height of his powers - world famous and busy on a project to record every major work for piano and orchestra with the great conductor George Szell.

He noticed a creeping numbness in two fingers of his right hand. Soon, the problem, called "focal dystonia," worsened until Fleisher was forced to retire from performance, triggering an epic personal crisis.

"I suffered abnormally," Fleisher recalls. "I was a clean shaven young youth and I grew a beard and ponytail and took off on a putt-putting Vespa scooter, because I didn't have the guts to go roaring around Baltimore on a BMW or a Harley-Davidson."

Shared joy

But he wasn't idle during the decades that followed, instead becoming a master of the works written for the left hand. Fleisher also became world-renowned as a teacher and has mentored many of today's great pianists. He believes a teacher's purpose is not merely to transmit technical advice but also to teach how to learn so that a student can make his or her own wise aesthetic choices.

Fleisher also became a distinguished conductor - a role that's far different from the solitary work of playing the piano.

"When you work with an orchestra you are working with 75 to 100 people, professional people, who are very possibly as advanced on their instrument as you were on yours, and that have sometimes a rather skeptical approach," he says. "And if you can talk an orchestra into first of all understanding what your vision of the music is, if you can persuade them to join you on the quest of realization of this vision, and they come along willingly and make every effort to realize this vision, that becomes a state of ecstasy. That becomes a kind of joy shared that is beyond words."

Despite his successes, Fleisher never stopped searching for a cure for his hand. Finally, in the late 1990's, a combination of Botox injections and a radical massage therapy called Rolfing offered some relief. His 2004 comeback album "Two Hands," was a triumph, as was his 2006 "The Journey."

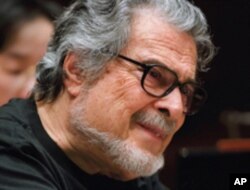

Prodigy. Concert pianist. Master teacher. Conductor. All these lives are recounted in Fleisher's just-published memoir "My Nine Lives," which he co-wrote with Anne Midgette. Now 82, Leon Fleisher hopes that his hand will continue to improve. Whatever happens, he says, he is still awed by the mysteries of music.

"You can't see music as it passes through the air. You can't grasp it and hold on to it. You can't smell it. You can't taste it. But it has a most powerful effect on most people. And that's a wondrous thing to contemplate."