During the eight-month fight against him, Moammar Gadhafi remained popular throughout much of Africa's Sahel region, south of Libya.

Gadhafi's favored status in the Sahel came from long-running investments in public and private projects, as well as the feeling that he was someone who stood up for Africa.

During the Libyan crisis, Niger allowed several convoys of former Gadhafi officials, including one of his sons, to cross into the country on humanitarian grounds. Burkina Faso briefly offered to give Gadhafi asylum.

Some lament Gadhafi's demise

In the Burkinabe capital Ouagadougou, businessman Marius Navarro said Africa is poorer without Gadhafi.

Navarro said Gadhafi's death is a huge loss for Africa and there is no doubt the continent will miss how much he did. Navarro said Gadhafi helped all of Africa, not only Libya. And because Africa did not support Gadhafi when he needed it, Navarro said Africa will ultimately come to regret losing him.

Gadhafi was one of the biggest financial contributors to the African Union. Burkinabe student Assita Compaore wondered about the future of the alliance without him.

Compaore said Gadhafi helped develop many African countries and Africans should mourn his death. In Burkina Faso, for example, he helped build a hotel and medical clinics, so Compaore said his death is a loss for the country and for all of Africa.

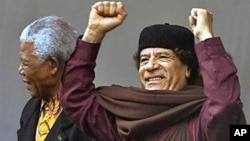

Gadhafi admirers recall Gadhafi's support for South Africa's African National Congress in the 1970s. Gadhafi detractors recall his support for brutish rebellions in Sierra Leone and Liberia in the 1990s.

Downside of Gadhafi's patronage

Burkinabe businessman Adama Badame said the ultimate cost of Gadhafi patronage was too high for Africa.

Badame said Gadhafi sold weapons to Africa that Africans used to kill each other. He said he is happy that the former Libyan leader is dead because he was a terrorist. He gives you food, Badame said, but then he gives you weapons that you use to kill each other. So Badame said better to have not received food from Gadhafi because after the food comes weapons.

Senegalese religious leader Ahmed Khalifa Niasse was a long-time political adviser to Gadhafi. Niasse, whose family is a powerful part of Senegal's Islamic Tijani brotherhood, said Gadhafi's death was a stand against outside aggression.

“I think his death was in a very honorable condition, fighting with his gun the foreigners attacking him from the sky in his country where he was born,” said Niasse.

Nigerian human rights activist Shehu Sani is the author of the book Civilian Dictators of Africa. He said the nature of Gadhafi's death makes him a martyr, whereas a trial would have exposed his brutality.

“No matter the crime he has committed, seeing a former president of a country being shot and dragged on the ground didn't go down well with people from this part of Africa,” said Sani.

Complicating factors of situation

Niasse believes Libya's new government will find it hard to rule because its mandate comes not from the Libyan people, but rather from Gadhafi's European opponents.

“Sarkozy, Cameron, and later on Berlusconi, they asked him to step down. Nothing was started by Libyans. Everything starts somewhere between Paris, Rome, and London. There is no popular revolution in Libya,” said Niasse.

There was a popular revolution in Libya. But NATO's involvement does distinguish it from popular uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt, which were largely unaided by foreign power.

Sani said that raises questions in the minds of Libya's southern neighbors about the priorities of a new government at a time of continuing concern about its treatment of sub-Saharan Africans, including ethnic Tuaregs who were part of Gadhafi's army.

“There is this anger in West Africa and the Sahel that black Africans have been targeted by elements of the rebel council and the new government in Libya,” said Sani.

Despite NATO support, Sani said Libya's neighbors are still Africans, and the security demands of a new government in Tripoli will depend largely on the security of those neighbors.