French far-right presidential front-runner Marine Le Pen offered a preview this week of what France’s foreign policy might look like if she is elected. She canceled a meeting with a top cleric in Lebanon over demands she wear a headscarf, and rejected the European Union, NATO and global trade deals in a keynote speech in Paris that favored an independent, France-first course.

“French policy will be decided in Paris,” she said Thursday, addressing a packed audience in a conference hall near the Champs Elysees. “No ally, no treaty, no alliance will decide policy in its place.”

Le Pen is running ahead in the polls despite being dogged by allegations of misusing EU funds. While many surveys find her winning the first round of voting in April, she is widely predicted to lose the May runoff vote. Yet in an election season marked by unpredictability and upsets, analysts are cautious about placing their bets, and mainstream EU leaders are tracking the popularity of Le Pen and other European nationalists with alarm.

‘A respect of culture and peoples’

In her speech, the 48-year-old National Front party head lambasted past EU and U.S. foreign policy for errors in the Middle East and toward Russia, and outlined a new French relationship with Africa free of meddling “but not indifferent.”

“I don’t want to promote a French or Western system,” she said. “I don’t want to promote a universal system, but to the contrary, I want to promote a respect of culture and peoples.”

While Le Pen has been largely shunned by many in the EU, she got red-carpet treatment in Lebanon earlier this week, where she meet with the country’s Christian President Michel Aoun and Sunni Prime Minister Saad Hariri, who warned her against confounding Islam with terrorism.

But she pointedly canceled a meeting with Lebanon’s grand mufti after refusing to wear a headscarf for the event, although his office said she had been told beforehand it was required.

While Le Pen’s tough stance on radical Islam, immigration and dual citizenship might put off many Arab countries, she might find common ground in the fight against terror, said Manuel Lafont Rapnouil, Paris office head of the European Council on Foreign Relations.

In a 2015 visit to Cairo, for example, she praised President Abdel Fattah el-Sissi for his fight against extremism, and “got a kind of official treatment by Egyptian authorities,” Lafont Rapnouil noted.

Champion of ‘oppressed people’

Le Pen’s discourse Thursday, touching on the Middle East, Africa and the United States, offered a stark counterpoint to her National Front’s more abrasive grassroots image as an anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim, populist party. She described France as a champion of “oppressed people, which speaks out for the voiceless and carries something powerful and great.”

She took no questions and continued calmly after a bare-chested Femen protester sought to interrupt her remarks before being carried, still shouting, out of the room.

Yet much of Le Pen's discourse was thin on specifics. She called for environmental security without defining it, and did not address key issues like whether France would stick to the Iran nuclear agreement under her leadership or to a two-state solution in the Middle East peace process.

“If you don’t pay attention to the details and just listen to the rhetoric, it sounds very French, very classical legalism,” Lafont Rapnouil said of Le Pen's traditional discourse. “If you pay a bit more attention, it’s a clear departure from the kind of mainstream foreign policy followed by France since the Cold War.”

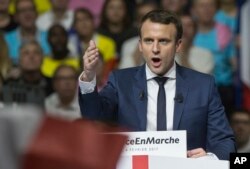

Like Le Pen, other presidential candidates are trying to bolster their international profile. Former economy minister Emmanuel Macron, who is running as an independent, met with British Prime Minister Theresa May during a visit to London this week, where he delivered a pro-EU message.

Former front-runner Francois Fillon, now battling a fake-jobs scandal, briefly met with German Chancellor Angela Merkel late last year in Brussels, according to reports.

EU bashing

Both candidates support remaining in the EU. Le Pen, by contrast, is sharply against the bloc, vowing to renegotiate France’s membership if elected and hold a ‘Frexit’ referendum if that fails. Adding to European concerns, far-right Dutch candidate Geert Wilders, another EU basher, is similarly coasting in the polls ahead of March elections in the Netherlands.

“The European Union is not the solution, it’s the problem,” Le Pen said Thursday.

“It will be a very difficult and cold relationship” with other European leaders if Le Pen becomes president, said analyst Philippe Moreau Defarges of the Paris-based French Institute for International Relations. "Of course, Mrs. Merkel or Theresa May will receive Mrs. Le Pen as head of state, but it will be a big European crisis, an earthquake, if she’s elected.”

Le Pen had kinder words for U.S. President Donald Trump whose November victory she praised early on and described as a harbinger of her own.

After sharply criticizing the Obama White House, she predicted the Trump administration represented “almost a change of software that will not only be positive for the world, but positive for the United States.”

Like Trump, Le Pen has embraced nationalist, law-and-order policies and a crackdown on immigration. She is also skeptical of multilateral institutions and trade agreements. But experts caution not to draw easy parallels.

Unlike the U.S. president, Le Pen has been in politics for years, holding both local office and a seat in the European parliament.

“I think she’s more prepared and classical in terms of institutions than Trump so far seems to be,” Lafont Rapnouil says.

Not business as usual

Still, he predicts a Le Pen presidency would be tumultuous, and realizing her promises like getting France out of the Schengen passport-free travel zone or the European Union would be challenging.

“On another level, most of her proposals would raise legal questions,” he added, that would likely end up in French and European courts. “This would not be business as usual, for sure.”

On defense, Le Pen reiterated her distaste for NATO, instead calling for a policy based on French national interests, and demanding a spending hike to two percent of GDP, increased to 3 percent by the end of her five-year term.

On the Middle East, she called for rapprochement with the Syrian government and Russia in the fight against Islamist terrorism, saying Moscow had been badly treated both by Europe and by previous U.S. administrations.