France’s controversy over the full-body swimsuit known as the burkini has exposed the country’s battle between its secularist society and its Muslim minority — at 7.5 percent of the population, the largest in Europe. Those tensions, some subtle and some not, have grown in the wake of terrorist attacks in a country that once prided itself on its welcoming attitude toward immigrants.

Far from the beaches, St. Etienne du Rouvray, a small community in the Normandy region of northern France, is still reeling from the murder of an elderly Catholic priest by two Islamic State jihadists in July, and there are fears the rapid growth of the Muslim population will result in a backlash led by the right but quietly supported by secularists on the left.

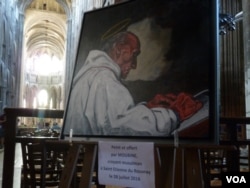

“It is for sure there will be problems,” said Antoinette Moulin, a parishioner at St. Therese Catholic Church, one of the parishes served by the late Father Jacques Hamel, 86, whose throat was slit in front of churchgoers as he celebrated Mass on July 26. “There is the issue of racism,” she said.

Countering discord

Both the Catholic and the Muslim communities have mobilized since Hamel’s death to defuse tensions and keep alive a spirit of goodwill that marked the relationship from the start.

“It is in our best interest to be together,” said Mohamed Karabila, the imam who heads the mosque next door to St. Therese. After Hamel’s killing, he invited Catholics to visit his mosque during Friday prayers. Catholic priests invited Muslims to attend Mass.

“There are those who are working to divide us, to sow hatred in the community. So we have begun to do acts to counter the discord,” Karabila said.

The murder is testing a relationship that began cordially decades ago, when North African immigrants began to arrive in the area to work for the French national railways’ sprawling rail yard and in factories in nearby Rouen.

St. Therese Church first allowed the Muslim newcomers to use its parish hall for prayers, and then donated part of its churchyard for construction of the community’s first mosque.

“There were people who found it a bit bizarre because the land was given to them for one franc at the time. It was symbolic,” said Moulin. “There were people who said, ‘Oh, now we’re going to have that mosque and there will be all these Arabs here.’”

Reinforcing brotherhood

The mosque, built next door in 2000, has thrived. Turnout is so high for Friday prayers that rugs have to be unrolled outside to accommodate the overflow, and neighbors complain about snarled traffic and illegal parking.

In contrast, fewer than half the pews were filled for a recent Sunday Mass at St. Therese, which like many Catholic parishes across France has seen attendance diminish to a few churchgoers, many of them elderly.

The growth of the area’s Muslim population has caused anxiety that has worsened since Hamel’s murder, the truck attack in Nice that killed 86 people in mid-July, and the deadly shootings and bombings in Paris last November.

“We are aware that people can turn to hatred against non-Christians and the risk is very great that people could hate Muslims because those who carried out these attacks claimed to be acting in the name of Islam,” said Father Auguste Moanda, the pastor at St. Therese and an associate of Hamel.

“It is true that the Catholic Church does not have many followers left, but it is at the heart of the country’s Christian tradition. Attacking the priest was symbolic and meant to push people to act against Islam,” he said. “But the intention failed. On the contrary, we sought to reinforce our brotherhood [with the Muslims].”

Anxiety

There is concern that fears over differences could be eroding the goodwill and giving rise to right-wing, anti-immigrant sentiments.

“The anxiety with which we are living with inevitably every day is because we are entering in France a period of preparation for the presidential elections," said Pierre Belhache, a priest in charge of Muslim relations at the Rouen diocese. "The debates are, let’s say, they are not always peaceful. The invective, the topics are very violent and could injure communities.”

The tensions are largely kept quiet. In Rouen, officials of the right-wing Front National declined comment. Since the attacks, the party’s numbers have gone up in the polls.

At the church where Hamel was killed, some are troubled by the silence.

“There is no great anger that I would notice. There is no movement, no uprising. But people will speak at the ballot box, for sure,” said Florence Giuliani, a local resident who stopped to lay flowers at a shrine outside the St. Etienne church where Hamel was killed.

In St. Etienne’s largely immigrant Chateau Blanc neighborhood, Ahmed Loutfy, owner of a halal grocery, worries.

“Here in France, many people think badly of Islam, and those people will vote for the National Front. It is automatic. It is going to happen, and we are afraid,” he said.

Some are looking with concern to the United States, and the possibility of how victory by Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump would influence French voters.

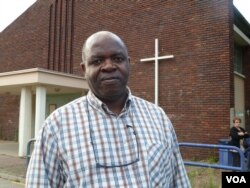

Gabriel Moba, an immigrant from the Democratic Republic of Congo and town councilor in St. Etienne du Rouvray, sees a clear link: “The French people who are angry, when they see the United States has elected someone with extremist views, they will say, ‘Why not do it over here?’”