Fossils including sharks, sea reptiles and squid-like creatures dug up in Idaho reveal a marine ecosystem thriving relatively soon after Earth's worst mass extinction, contradicting the long-held notion life was slow to recover from the calamity.

Scientists on Wednesday described the surprising fossil discovery showing creatures flourishing in the aftermath of the worldwide die-off at the end of the Permian Period about 252 million years ago that erased roughly 90 percent of species.

Even the asteroid-induced mass extinction 66 million years ago that doomed the dinosaurs did not push life to the brink of annihilation like the Permian one.

The fossils of about 30 different species unearthed in Bear Lake County near the Idaho city of Paris showed a quick and dynamic rebound in a marine ecosystem, illustrating the remarkable resiliency of life.

"Our discovery was totally unexpected," said paleontologist Arnaud Brayard of the University of Burgundy-Franche-Comte in France, with a highly diversified and complex assemblage of animals.

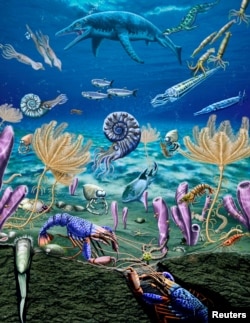

The ecosystem from this pivotal time included predators such as sharks up to about 7 feet long (2 meters), marine reptiles and bony fish, squid-like creatures including some with long conical shells and others with coiled shells, a scavenging crustacean with large eyes and strangely thin claws, starfish relatives, sponges and other animals.

The Permian die-off occurred 251.9 million years ago. The Idaho ecosystem flourished 1.3 million years later, "quite rapid on a geological scale," according to Brayard. The mass extinction's cause is a matter of debate.

But many scientists attribute it to colossal volcanic eruptions in northern Siberia that unleashed large amounts of greenhouse and toxic gases, triggering severe global warming and big fluctuations in oceanic chemistry including acidification and oxygen deficiency.

The Idaho ecosystem, in the earliest stages of the Triassic Period that later produced the first dinosaurs, included some unexpected creatures. There was a type of sponge previously believed to have gone extinct 200 million years earlier, and a squid-like group previously thought not to have originated until 50 million years later.

The researchers found bones from what could be the earliest-known ichthyosaur, a dolphin-like marine reptile group that prospered for 160 million years, or a direct ancestor.

"The Early Triassic is a complex and highly disturbed epoch, but certainly not a devastated one as commonly assumed, and this epoch has not yet yielded up all its secrets," Brayard said.

The research was published in the journal Science Advances.