It is a day associated with new beginnings, but for a growing number of Syrian refugees in Lebanon, marriage has become a trap.

Strapped for cash, unfamiliar with the laws of the land and often restricted in their ability to find someone to conduct the marriage, growing numbers of couples are tying the knot illegitimately.

The implications are profound, with consequences reverberating across generations and the country. Children of such unions risk being left without status and rights.

Rushed into marriage

Having fled her home of Idlib, Syria for Lebanon in 2013, the prospect of marriage arose suddenly for Reja, whose family name has been withheld to protect her identity.

“I love my father very much, so when he said marriage would be good for me I decided not to say no,” the 28-year-old explained.

It happened in a whirlwind. Within a day she had met her future husband (Reja requested his name was withheld) and within two days the pair were marrying.

Yet Reja spotted something was amiss.

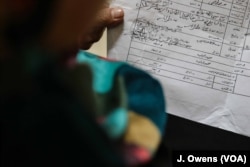

“We could not get a sheikh at the time, so my father oversaw the ceremony and the handwritten contract," she said. “I suspected that it was not legal, but after the marriage my husband would always find an excuse not to deal with it.”

As a woman, Reja felt it inappropriate to pursue the issue herself, but she was right to be suspicious.

Unforeseen consequences

Had Reja and her husband been married in Syria, the marriage would likely have been seen as legitimate, as the laws there are less stringent.

But in Lebanon, a verbal contract and religious ceremony are not enough. The marriage must be conducted with a registered Sheikh and get state approval, a process that can be costly.

Though some Lebanese face the same problem, Syrian refugees are the group most affected, explained Ranin Osman, a lawyer.

“Maybe they do not have the money, that’s one reason. Secondly, they may not be aware they have to do it, and thirdly they may be lied to by an unregistered sheikh,” said Osman, who works with those affected by the practice.

There are as many as 1.5 million Syrian refugees in Lebanon, and though there are no official estimates for how many people might be affected, Osman warns it is “a very big problem”.

The consequences of not registering a marriage can be severe.

After a miserable few years in which she said she was badly mistreated by her husband, the final straw for Reja came when she discovered he was preparing to marry another woman.

Having spoken to The Lebanese Council to Resist Violence Against Woman, one of the few organizations looking into the issue, she registered the marriage so she could get a legally-recognized divorce.

Registering the marriage gave her the legally enforceable means to demand child support from her now ex-husband.

“I will be getting $135 a month for my two children, and that is so important for them.”

Stateless

The future of her children remains far from secure.

At the offices of The Lebanese Council to Resist Violence Against Woman in Tripoli, Saraa Dannawi explained if parents don’t register their marriage they cannot register the child.

Registering children before they are a year old is relatively cheap, but after their first birthday it can becomes prohibitively complex, bureaucratic and expensive.

According Ramy Israkhieh, director of the Tripoli International Centre for Human Rights, the fact many refugees have run out of money is exacerbating the issue.

“I would say there has been a 30 percent increase in people coming to us with this issue in the past two years,” he explained to VOA News.

According to the U.N. refugee agency, only 19 percent of families reported all members had legal residency, down from 21 per cent in 2016.

The children whose births remain unregistered face being deprived of access to basic services such as education and medical care. They are unable to get a Syrian passport or ID, and thus cannot legally return to the country of their parents. They become stateless.

In short, as Dannawi warned, “the child risks losing everything.”

Statelessness presents a problem for the Lebanese state too. More and more of its population is becoming untraceable and statelessness presents a potential barrier to Syrians who wish to repatriate when the war ends.

Reja worries in particular about the upcoming prospect of school, and whether her daughter will be able to attend.

More broadly, she fears her her children will fall between the cracks of society because of their status. “I don’t want them to have issues with the law here,” she explains. “I am scared about their future.