Rights activists and refugees have expressed concerns over the United Nations food agency's decision to cut food aid for the second time in three months for more than 1 million Rohingya from Myanmar who are currently living in shanty colonies in Bangladesh.

Because of a fund shortage, the World Food Program on June 1 cut its monthly food rations for the Rohingya refugees from $10 per person to $8. This amounts to less than nine cents per meal, according to the WFP in a news release late last month.

The cut follows a previous one in March, when, citing a fund crunch, the WFP reduced the monthly food aid from $12 to $10 per person.

'Many will starve now'

The World Food Program said it was experiencing a $56 million shortfall, resulting in the latest cut in rations.

Dom Scalpelli, WFP resident representative and country director in Bangladesh, said in the statement that the United Nations food agency was appealing for "urgent support" to be able to "restore rations to the full amount as soon as possible."

"Anything less than U.S. $12 has dire consequences not only on nutrition for women and children but also protection, safety and security for everyone in the camps," Scalpelli said in the statement.

Abdul Kalam, a Rohingya living at Balukhali camp in Cox's Bazar, said that the latest cut is a "terrible blow" to the refugee community in Bangladesh.

"Trying to manage their families — many will starve now," he said.

"We are extremely concerned that WFP has been forced to cut food aid for the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh," Gwyn Lewis, the U.N. resident coordinator in Bangladesh, said last week (June 1). "The nutrition and health consequences will be devastating, particularly for women and children and the most vulnerable in the community. We urgently appeal for international support."

Rice, lentils, oil

To escape persecution and violence in Myanmar, minority Rohingya Muslims have for decades fled to neighboring Bangladesh.

Not being allowed to engage in any livelihood-related activities outside the camp by Bangladesh authorities, the Rohingya refugees are completely dependent on food aid provided by the WFP.

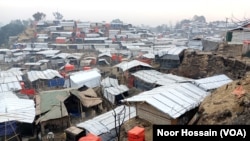

Living in bamboo and tarpaulin shanty colonies in Cox's Bazar, Rohingya refugees say that the monthly food aid of $12 per person that they used to get before March was already very limited when they were forced to survive only on staples such as rice, lentils and oil, and that most suffer from malnutrition.

"We are not provided with any clothing assistance from any organization. Like many others, I sometimes resorted to selling a portion of our food rations to buy clothing and also fish or beef, for my family. After the food ration has been cut by one-third, we are going to face a terrible level of hardship from this month," Rohingya refugee Kalam, 42, who lives in Kutupalong camp in Cox's Bazar with his family, told VOA.

"The devastating blow of this cut leaves me with no choice but to contemplate the unimaginable — accepting a repatriation offer, despite the fact that our fundamental rights remain unrecognized and unfulfilled by the Myanmar authorities, he said. "The thought of witnessing my children suffer the pangs of hunger proves unbearable, prompting me to consider a return to my war-torn homeland."

The WFP food ration has been reduced twice in the past three months, even though many refugees hoped it would be increased.

Abu Jafar, another Rohingya refugee from Balukhali camp said, "Prices of many food materials have doubled over the past three years. To cope with the growing inflation, we have been praying for a hike in food ration. I cannot figure out how I will manage my family now. There is no way to escape starvation."

'Not just a matter of hunger'

Cox's Bazar-based Rohingya community leader and human rights defender Htway Lwin noted that "the reduction of food assistance for Rohingya refugees is not just a matter of hunger."

"It is a catalyst for a chain of devastating consequences for the refugees, including an increase of their involvement in criminal activities and exploitation by pimps and smugglers," Lwin told VOA.

"Ultimately, we are going to be forced to make unimaginable choices to survive, compromising our dignity and future. This is not the way any human being should be forced to live," Lwin said.

John Quinley, director of the human rights organization Fortify Rights that works among the Rohingya, told VOA that the food ration cuts are having dire consequences for Rohingya, particularly children.

"There are already high levels of malnutrition in the refugee camps in Bangladesh," Quinley noted.

"Bangladesh is restricting refugees' right to work." Quinley said. "The authorities must allow middle-term solutions, including work and livelihood opportunities for refugees. Donor governments must commit funds to Rohingya response, including ASEAN and OIC countries." ASEAN refers to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, and OIC is the Organization of Islamic Cooperation.

Noting that "it's absolutely shocking," Phil Robertson, deputy director of Human Rights Watch's Asia division, said that the international community is "slinking away from their solemn obligations" to help the Rohingya.

"The Rohingya refugees have next to nothing, and now they are being told their food rations will be cut because the donors haven't come up with the money. Bangladesh was promised that if they took the Rohingya in, the global donor community would shoulder the burden, but now it's clear that bargain is breaking down," Robertson told VOA.

All this is leading to an impetus toward tragedy, with both Bangladesh and Myanmar raising pressure on the Rohingya to return to Myanmar's Rakhine state without guarantees of freedom of movement, full citizenship, and protection from harm, he added.

"The Rohingya are increasingly stuck between a rock and a hard place as international donors act to wash off their hands and move on to the next tragedy," he said.