The seas are angry this month.

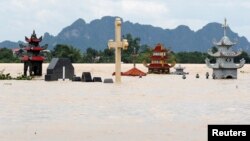

While the remnants of Hurricane Florence soak the Carolinas and Typhoon Mangkhut pounds the Philippines, three more tropical cyclones are spinning in the Western Hemisphere, and one is petering out over Southeast Asia.

Experts say some of this extreme tropical weather is consistent with climate change. But some isn’t. And some is unclear.

It’s unusual to have so many storms happening at once. But not unheard of.

“While it is very busy, this has happened a number of times in the past,” said meteorologist Joel Cline at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Mid-September is the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season. If there are going to be storms in both hemispheres, Cline said, now is the most likely time.

Stronger storms, and a grain of salt

Scientists are not necessarily expecting more hurricanes with climate change, however.

“A lot of studies actually (show) fewer storms overall,” said NOAA climate scientist Tom Knutson.

“But one thing they also tend to simulate is slightly stronger storms” and a larger proportion of Category 4 or 5 hurricanes, Knutson said. Florence made landfall as a Category 1 storm but started the week as a Category 4.

Knutson and other experts caution that any conclusions linking climate and hurricanes need to be taken with a grain of salt.

“Our period of record is too short to be very confident in these sorts of things,” said University of Miami atmospheric scientist Brian McNoldy.

While reliable temperature records go back more than a century in much of the world, comprehensive data on hurricanes only starts with satellites in the 1980s.

Extreme rainfall

Scientists are fairly sure that climate change is making extreme rainfall more common. Global warming has raised ocean temperatures, leading to more water evaporating into the atmosphere, and warmer air holds more water.

Florence is expected to dump up to 101 centimeters (40 inches) of rain in some spots, leading to what the National Weather Service calls life-threatening flooding.

One group of researchers has estimated that half of the rain falling in the hurricane’s wettest areas is because of human-caused climate change.

Knutson agrees in principle but can’t vouch for the magnitude.

“We do not yet claim that we have detected this increase in hurricane rainfall rate,” he said.

He points to earlier studies that blamed climate change for 15 to 20 percent of the devastating rainfall Hurricane Harvey poured on Texas last year.

However, these studies looked at all kinds of rainfall, not just hurricanes, Knutson notes.

“We think that hurricanes are probably behaving like the other types of processes, but we have the best data for extreme precipitation in general,” he explained.

The latest United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report has “medium confidence” in the link between climate change and rainfall extremes.

As Florence trudges across the Carolinas, one recent study suggests that hurricanes are moving slower, giving them more time to do their damage.

But that may be natural variation more than climate change.

“I think we’re still early in the game on that one,” Knutson said.

Rising sea levels

The area where scientists are most confident is sea level rise. Climate change is responsible for three-quarters of the increase in ocean levels, according to the IPCC report.

“Once you have human-caused sea level rise, then all other things being equal, whatever storms you have will create that much higher storm surge,” Knutson said.

That means more erosion and more damage farther on shore.

Whether this hurricane season as a whole will be one for the record books remains to be seen. While the seas are angry at the moment, that may soon change.

An El Niño warming pattern appears to be developing in the Pacific. That tends to squash hurricane activity in the Atlantic.

“It appears that perhaps next week will be much more quiet in both basins,” said NOAA’s Joel Cline. “So it does ebb and flow.”