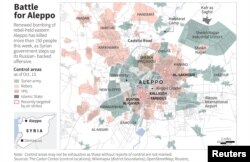

Fierce clashes broke out this weekend in the besieged Syrian city of Aleppo, hours after a three-day cease fire ended with Russian and Syrian government warplanes launching waves of airstrikes and rebel militias targeting western districts held by Assad government troops with Grad rockets newly supplied by Gulf backers.

While international attention focused on the unfolding offensive on Mosul, the Islamic State’s last major urban stronghold in Iraq, big battles are shaping up in northern Syria.

As fighting intensified Sunday in Syria’s onetime commercial capital, just north of Aleppo Turkish-backed rebel militias, some also allied with the United States, launched an assault on the town of Tel Rifat in a bid to retake it from Western-aligned Kurdish fighters who ejected local Arabs when they overran the town last February.

The Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces says it seized Tel Rifat and a clutch of neighboring villages to prevent them from falling into the hands of forces loyal to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, during a blistering Russian-backed offensive. But the Kurdish fighters expelled Arabs and have refused to allow them to return, according to several refugees from Tel Rifat interviewed by VOA last month at a refugee camp in southern Turkey.

The seizure enraged rebel militias, who accused the Kurds of treachery and pledged to retaliate and take back Tel Rifat, historically an Arab town.

Civilian plight

The resumption of fighting in Aleppo and the clash between rebels and Kurds north of the city is worsening the already desperate plight of civilians warn U.N. officials. Relief agencies had hoped to get aid into the besieged rebel-held eastern districts of the city during a three-day unilateral pause in hostilities announced last week by Russia.

On Friday, U.N. officials said no aid got in, and because both warring parties refused to give security guarantees planned medical evacuations were cancelled.

Syrian state media and Russian authorities accused the rebels in the east of preventing civilians from leaving and of using them as “human shields”, an accusation strongly denied by rebel leaders, who say most civilians aren’t leaving because they mistrust the Assad government and fear what will happen to them after they leave.

Some who wanted to flee down a “humanitarian corridor” opened by Assad forces couldn’t do so because of fighting. “Nobody has left through the corridors," Zakaria Malahifji, a commander with a Free Syrian Army militia, says. “Some who wanted to, couldn’t leave because of shelling nearby,” he added.

Up to 300,000 civilians are thought to be in eastern Aleppo. They have little food and woefully inadequate medical care, Syrian and Russian warplanes have repeatedly struck hospitals. No aid has entered Aleppo since July 7 and food rations will run out by the end of October, U.N. chief Ban Ki-moon warned Thursday.

French medical charity Doctors without Borders said Saturday the few medical supplies in eastern Aleppo are running out. “Aleppo’s seven remaining hospitals cannot cope for much longer,” it warned.

A monitoring group, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a British-based clearing house of information gathered by political activists in Syria, said the resumption of airstrikes Saturday came quickly after the cease-fire had ended. The United Nations had asked Moscow and Damascus to extend their pause in hostilities until Monday.

As warplanes struck, rebels retaliated with new arms supplies and launched Grad rocket attacks mainly targeting a military academy and al-Nayrab military airport southeast of Aleppo. But Grad attacks were also reported on civilian areas in the western parts of the city.

As airstrikes intensified overnight, the mother of seven-year-old Bana Alabed, the little girl whose tweets from inside eastern Aleppo that started to go viral earlier this month, tweeted: “Bad night and day. Ceasefire ended, bombing started.”

Both sides had used the pause in hostilities to re-order their forces. A senior Russian military official, Sergei Rudskoi, said Saturday, “We are seeing them [the rebels] massing around Aleppo and preparing for another breakthrough into the city’s western neighborhoods.”

With new supplies of Grad rockets, the rebels are hoping to break the months-long encirclement by government forces of their eastern districts. Abdel Salam Abed, a spokesperson of the al-Zinki militia, said rebel brigades are preparing an offensive to break the siege.

The new phase in the battle for Aleppo “may be the biggest and most significant battle of the Syrian war,” says Robin Yassin-Kassab, the co-author of the book Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War.

If Assad forces backed by Russian airpower are able to overrun the eastern half of the city, it would amount to the biggest reversal of rebel fortunes in the five-year civil war, dealing a devastating symbolic and strategic blow to the rebellion.

But if the rebels can manage to hang on or break the encirclement, it would demonstrate that no amount of Russian firepower can subdue the insurgents, say analysts.