In a tent museum on the sunny grounds of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, Rosario “Charito” Planas rolled in her wheelchair through room after room of reminders of forced detentions, disappearances and killings during the martial law years in the Philippines.

The two-day exhibit is commemorating the 30th anniversary of the “People Power Movement” that ousted then dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

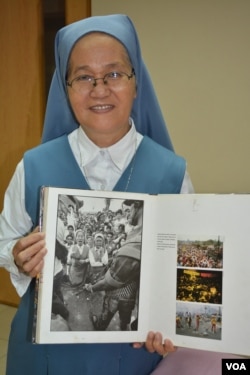

Planas, 85, had a long history of political activism, working with political opponents of Marcos. In the early 1970s, she was detained in solitary confinement and then placed under house arrest for well over a year. In 1979, she fled the Philippines disguised as a nun and received asylum in the United States.

After coming out of the exhibit, Planas implored young people born after the 1986 revolution to visit.

“They should be the torch-bearer. But instead they are the computer-bearer. It’s sad,” she said.

Planas, like a significant number of other adults who lived through the martial law years, lamented the seeming lack of interest in that period.

More concerning for her is that Marcos’ son Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr. is running for vice president in the Philippines’ May elections.

Ramon Casiple, executive director of the Institute for Political and Electoral Reform, said political dynasties “are at the heart” of the country’s political problems three decades after democracy was “restored.”

“Democracy, or the benefits of democracy, has been limited primarily to the elite,” said Casiple. “That’s why the term ‘elite democracy’ can be applied to that. And part of that change actually, or maybe you can call it non-change, is the persistence of the Marcos people, including the family itself.”

Casiple pointed out that a recent poll by a Philippine-based research group shows Marcos Jr. leading the VP race. He expects that among millennials, which make up one third of the country’s more than 54 million voters, Bongbong Marcos will get a large share of the votes.

Many of the millennial generation were not yet born when millions of Filipinos converged for days on Epifaño de los Santos Avenue (or EDSA) fronting Philippine military and police headquarters and demanded the ouster of Marcos. They said Marcos had stolen a hastily called February election in which Corazon Aquino, widow of Benigno Aquino Jr., the slain and widely respected opponent of Marcos, had a significant majority of votes.

“Their thinking about 1986 is mixed. For the most part they don’t care. I mean they did not have those personal experiences of how to live under a martial rule situation,” said Casiple.

He added that some young adults see the dictatorship as a “paradise” and they espouse a return to that style of government. He also said the other view was that of young people “who knew their proper history” whose parents lived through some of the brutal law and order practices of the regime.

Richard Amazona, program officer of the Manila-based Young Public Servants of the Philippines said his group, which is 20,000 strong through ties to other youth organizations, is non-partisan and opposes political dynasties.

“We believe that it’s a hindrance to development and it doesn’t provide any other option for other Filipinos to really select the best candidate for the position,” he said.

Amazona, 23, said even if the group does not endorse any candidate, it is closely watching the Marcos surge in the polls and takes the position that “Filipinos have the capacity to decide… with intelligence” for themselves.

“With the things that had happened 30 years ago through the EDSA Revolution, we can say that it is also our battle cry to really ensure that the same scenario does not happen again with our generation,” he said.

Casiple said there have been some positive strides in the past 30 years with the country making a dent in its poverty rate, from 32 percent to 25 percent, and also achieving a handful of the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals.

But he said apart from the persistence of the same families running government at all levels across the country, the vote-buying and corruption that became prevalent under the Marcos regime continues today.

The EDSA People Power Commission, a body under President Benigno Aquino’s office, put up the temporary “experiential museum.”

Commissioner Emily Abrera said the prevailing sentiment in 1986 was that a change in leadership was all that was needed. She said the Philippines “kicked out the bad guy,” but it also became aware of just how deeply engrained corruption was.

“It will take, two or three excellent regimes, two or three presidents who are outstanding in their personal integrity,” she said. “Because we will need that to clearly see the difference.”