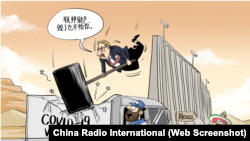

On October 26, China Radio International (CRI), the Chinese state-owned international radio broadcaster, published on its website a cartoon captioned, “I’d rather destroy them than give them to you.”

The cartoon depicts a man in suit and tie – representing a White House official – swinging a hammer to smash a container truck loaded with COVID-19 vaccines. The truck, with “civil society donation group” printed on the side, is poised at the U.S.-Mexico border. A character in a sombrero and poncho appears disappointed.

“Recently, U.S. civil society plans to donate thousands of doses of COVID-19 vaccine to Mexico, but the White House Vaccine Task Force said that COVID-19 vaccines are federal property, [they] do not allow donation, and [they] destroyed those vaccines,” says the description for the cartoon. “The United States Government has done this more than once to prevent civil society from donating excess vaccines to countries in need.”

That portrayal is misleading.

To be sure, the U.S. federal government has stopped state and local health authorities from donating unused and expiring vaccines internationally, but the ban is due to reasonable legal and logistical hurdles. As the shelf life runs out, vaccines are destroyed.

In fact, Mexico is the top recipient of U.S. vaccine donation among Central and South American countries, with nearly 11 million doses delivered as of October 20.

The cartoon follows a Washington Post report on October 22 describing how a small group of health professionals and officials in southern California readied a plan to donate thousands of doses of COVID-19 vaccines nearing expiration date to Mexico only a short drive away. The White House Vaccine Task Force vetoed the plan, and the vaccine doses ended up being tossed out, the Post reported.

President Joe Biden’s administration has explained that the vaccines doses are federal property. “That means the federal government is liable for their use, and donation efforts must be run out of Washington,” according to the Post.

Strict conditions must be met for delivering, storing, and handling the vaccines, especially for mRNA vaccines manufactured by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna.

For the delivery of Pfizer-BioNTech doses, for example, vaccines must arrive “at a temperature between -90C and -60C (-130F and -76F) in a thermal shipping container with dry ice to maintain proper temperatures,” according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Though the CDC allows different types of cold-storage equipment of varying temperature ranges for vaccines storage, each method comes with a different shelf life for the vaccines. There is no standard to ensure that state and local providers can safely gather and transport expiring doses.

“At least right now, there’s not any kind of system or mechanism to provide any quality assurance to this,” Dr. Marcus Plescia, chief medical officer for the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, told the Post.

Several states had attempted in early summer to send surplus vaccines overseas on their own, Plescia told POLITICO in June. But the states eventually concluded that the federal government “was better equipped to work out the complicated donation logistics.”

“The big concern is that they are going to expire,” Plescia told POLITICO. “Some of the doses are just a few weeks away from that.”

“As they get close to expiration date, what are the ethics of trying to ship them off to another country?” Plescia added.

Though the federal government is exploring ways to reabsorb unused vaccines to be donated internationally, federal officials told the Post that because vaccines are dispersed so widely, gathering them could be tricky and costly.

One of the legal challenges comes from the contracts signed with vaccine manufacturers under Biden’s predecessor, Donald Trump, first reported by Vanity Fair in April. The agreements with Pfizer, Moderna, AstraZeneca, and Janssen state: “The Government may not use, or authorize the use of, any products or materials provided under this Project Agreement, unless such use occurs in the United States” or U.S. territories.

That clause was added by the manufacturers to ensure that they retain liability protection should their vaccines cause harm. In the United States, a law called the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act (PREP Act) offers immunity to the manufacturers and provides compensation to the individuals who suffered injuries from the administration of vaccines.

The U.S. government had sidestepped the contractual limitations by “loaning” vaccines to Mexico and Canada, though those countries still had to indemnify the manufacturers.

An Indian online newspaper, ThePrint, reported in July that the indemnity issue became the logjam that held up U.S. vaccine donations to India.

Govind Persad, a professor at the University of Denver Sturm College of Law, urged the U.S. government to do the same with other countries who are willing to make similar agreements and “feel confident they can use soon-expiring vaccines.”

As vaccine shortages still plague many parts of the world, the Biden administration has been criticized for sitting on and wasting millions of surplus doses. Both domestic and international pressure has been mounting on the United States to move its unused doses to countries in need.

“It’s hard to believe that it’s ever better to let doses expire and throw them away rather than put them to use,” Jess Mandel, chief of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of California at San Diego School of Medicine, told the Post.

Some public health officials have said that state and local donation efforts should be allowed if the recipient countries are willing to sign waivers, reported the Post.