On October 10, Wang Wen, executive dean of the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at Renmin University of China, published an article in which he defended Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Wang visited Russia in September, including Crimea, where he met with top officials of the Black Sea peninsula’s Russia-imposed government. He boasted on his blog that more than 160 Russian media outlets reported on “the first trip by a Chinese think-tank scholar to Crimea.”

He said the trip had “great academic value in understanding the developments of Russia-Ukraine conflict, deeply grasping the future situation of Russia and other significant issues.”

In his article for Guancha.cn, Wang showered praise on Russian-ruled Crimea for what he described as its “rapid economic growth in eight years.” He also lamented the “rocky future” Crimea faces due to the ongoing war, which Russian President Vladimir Putin launched against Ukraine in February.

He described what happened to Crimea eight years ago as follows:

"After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the issue of who owns the Crimean Peninsula became a long-standing dispute between Ukraine, Russia and the local government of Crimea. Crimea had been constantly calling for full independence or returning to Russia, with the situation around it tightened and loosened until March 16, 2014, when there was a referendum in Crimea and over 96% of the voters favored Crimea’s accession to Russia.

“Russia said it respected and supported the choice of the Crimean people. Two days later, Russian President Vladimir Putin approved Crimea’s accession to the Russian Federation."

That characterization of Russia's invasion and takeover of Crimea is misleading.

Crimea has been part of Ukraine since 1954, when then-Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev transferred the Crimean Oblast from what was then the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, or RSFSR, to what was then the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, or UkrSSR. The presidium of the Supreme Soviet, the Soviet Union’s legislature, formally authorized the transfer. Historians are still debating the motivation behind the transfer.

Prior to that, Crimea had been part of Russia since 1783, when Russian Tsarina Catherine the Great annexed the peninsula from the Ottoman Empire after the invading Russians defeated the Ottoman forces.

Before the tsarist annexation, however, Crimea had existed as the Crimean Khanate, an Ottoman Empire protectorate, for more than three centuries starting in the mid-1400s. According to some historians, the name “Crimea” was from the language of the Crimean Tatars, “a Turkic ethnic group that emerged during the Crimean Khanate,” The Washington Post reported in 2014.

During the time Crimea was ruled by imperial Russia and then the Soviet Union before 2014, the indigenous Crimean Tatars, along with large numbers of Greeks, Armenians and other ethnic groups, were persecuted and expelled from the peninsula by both regimes. Crimea eventually became predominantly Russian, reaching 60% of the Crimean population in 2001, with Ukrainians constituting 24%, after the waves of deportations of the indigenous populations.

According to official Crimean, Soviet and Ukrainian census data, the Crimean Tatars’ share of the peninsula’s population dropped from 34.1% in 1897 to zero in 1959, climbing back up to 12% by 2001.

The Washington Post explained the drastic drop of the Crimean Tatar population to zero in 1959 this way:

“Once the [Soviet] Red Army retook Crimea [from Nazi Germany] in 1944, it forcibly deported the entire population of Crimean Tatars to Central Asia as punishment for collaboration with German forces. Almost half are believed to have died along the way. The Tatars, who had been on the peninsula for centuries, were not allowed to return to Crimea until the end of Soviet Union.”

Crimea formally became part of the Soviet Union in 1921, when it was established as the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. The republic was transformed into the Crimean Oblast in 1945, an administrative region of Soviet Russia, until its transfer to Soviet Ukraine in 1954.

“Crimea was part of Soviet Ukraine for longer than it was part of Soviet Russia,” wrote Orysia Lutsevych, research fellow at Britain’s Chatham House think tank.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, “many apparently expected new President Boris Yeltsin to demand that Crimea be returned to Russia,” The Washington Post noted. But that didn’t happen.

Even though 60% of Crimea’s population was ethnic Russian, 54% of the peninsula’s voters favored remaining part of Ukraine in a December 1991 Ukrainian referendum on independence.

“It was a majority, but the lowest one found in Ukraine. Following a brief tussle with the newly independent Ukrainian government, Crimea agreed to remain part of Ukraine, but with significant autonomy,” wrote The Washington Post.

Crimea became the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (ARC), the newly independent Ukraine’s only self-governing region. The ARC had its own constitution, legislature and prime minister.

It remained that way until Russia’s invasion and annexation of Crimea in 2014, which followed the ouster of Ukraine’s pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych amid a wave of Ukrainian populist protests.

Masked men wearing Russian-style combat uniforms without identifying insignia and carrying Russian weapons moved into Crimea on February 27, a few days after Yanukovych fled to Russia. The locals called them “little green men.”

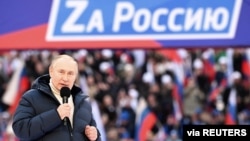

These troops seized control of Crimea. Putin and other Russian officials initially denied they were Russians and called them “self-defense units” organized by Crimean locals. A year later, however, Putin admitted on television the units were actually Russian forces he had ordered into Crimea.

A referendum was staged – under the Russian military occupation – on March 16, 2014, in an internationally condemned attempt to legitimize permanent annexation of Crimea to Russia.

“Crimea's March referendum on leaving Ukraine for Russia ostensibly garnered 97% support, but it occurred in a rush, without international monitors, and under Russian military occupation,” Vox news reported in 2014.

“A draft U.N. investigative report found that critics of secession within Crimea were detained and tortured in the days before the vote; it also found ‘many reports of vote-rigging.’ Had the referendum been held in a transparent and legal manner, it's not clear which way the vote would have gone.”

As Reuters reported in March 2014, Crimean voters could only choose between full or partial takeover by Russia, without an option to remain part of Ukraine.

Chatham House’s Orysia Lutsevych reported that the Kremlin “substantially inflated voter turnout.”

“While it said that 82% of voters had cast their ballots, a member of Russia’s presidential Civil Society and Human Rights Council reported that turnout was likely to have totaled 30–50%. Election fraud such as multiple voting was also reported,” Lutsevych wrote in May 2021.

“Public opinion polling prior to Russia’s aggressive disinformation campaign spoke clearly in favor of Crimea remaining part of Ukraine,” Lutsevych said, citing a May 2013 opinion poll conducted by the Baltic Surveys/Gallup on behalf of the International Republican Institute, a U.S. non-profit organization.

The survey showed that 53% of respondents wanted Crimea to remain part of Ukraine and only 23% said they would rather have Crimea separated from Ukraine and join the Russian Federation.

Backed by 100 members including the United States and European Union, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution on March 27, 2014, condemning the referendum as invalid. China abstained in the voting.

China has toed a fine line when it comes to Russia's annexation of Crimea and support for Ukraine's territorial integrity since the war began. According to an article last month in the Chinese Communist Party paper Global Times:

"Cui Heng, an assistant researcher at the Center for Russian Studies at East China Normal University, told the Global Times on Friday that China has adhered to its principle of stressing countries' sovereignty and territorial integrity, which means we respect the sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of all countries.

" 'Just like China's position on Crimea in 2014, we always adhere to the principle of territorial integrity and sovereignty,' Cui said.

"In response to questions on whether China would recognize the referendum results in Crimea, a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson said at a media briefing on March 17, 2014 that China always respects the sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of all countries."