During his presidential campaign, Democrat Joe Biden often promised to undo then-President Donald Trump's immigration policies. Now, approaching two months in power, the Biden team confronts an increasing number of migrants trying to get into the U.S. from Mexico.

Some are calling the situation on the southwest U.S. border a “crisis” – including Trump, fellow Republicans and West Virginia Democratic Senator Joe Manchin – while new Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas frames the situation more neutrally as a difficult “challenge.”

Amid the political jockeying, the official numbers used to track immigration can be easily misconstrued or sometimes misrepresented. Biden’s critics want things to look catastrophic; his defenders see less cause for alarm. Hence this fact-check.

We take House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy as an example because, on March 5, he sent a letter to Biden in which he attacked Mayorkas for allegedly inviting illegal immigrants and referred to “drastic increases” in apprehensions by the Border Patrol.

“You confirmed this week that you received a briefing on the situation at the border that, according to press reports, included information indicating upwards of 117,000 unaccompanied alien children (UAC) will be crossing the southern border this year,” McCarthy, a California Republican, wrote to Biden.

McCarthy added that January’s data “shows a nearly 113% increase in UAC [unaccompanied alien children] apprehensions when compared to January 2020. Total apprehensions in January show a 157% increase compared to January 2020.”

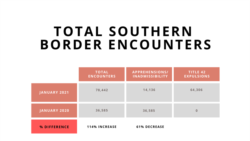

Both of these numbers appear to be exaggerated based on official figures put out by U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, which nonetheless do show an increase in encounters.

Definitions matter

First, it’s important to know just what’s being counted.

Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) uses the umbrella term “encounter” to describe what happens when migrants reach the border. And there are two types of encounter:

“Inadmissibles” includes people who do not have legal status arriving at ports of entry seeking lawful admission or humanitarian protection. Inadmissibles will normally enter U.S. territory while waiting for their case to proceed or pending an expedited removal.

The second category, “apprehensions,” includes people who are not lawfully in the U.S. and who may be temporarily detained and possibly arrested before being deported.

Thanks to the pandemic, however, there is effectively a new type of encounter. Citing health risks, the Trump administration adopted a policy allowing Border Patrol to refuse entry to anyone, including solo children, who might pose a health risk. People in this group are simply sent back to Mexico and never enter the country.

This category of expulsions – referred to as Title 42 – accounts for the bulk of the increase in border encounters over the past 12 months. And it’s a critical piece of left-out context.

In January 2021, out of 78,442 encounters, there were only 14,136 apprehensions/inadmissibles, CBP figures show. That marked a 61.4% decrease in apprehensions/encounters when compared to January 2020 – not a 157% increase, as McCarthy claimed.

Adults made up 65,185 encounters, and 9 out of every 10 were turned away under Title 42. So, while it’s true that more people showed up in January than a year earlier, most were rejected.

Statistics from February 2021, released five days after McCarthy posted his letter, show a 28 percent rise in encounters over January, reaching 100,441 – the highest monthly figure since mid-2019, a time of historic highs. Again, however, nearly 72% of those people were turned back.

Besides the pandemic policy, another oft-overlooked factor colors the border stats – recidivism. That is the rate at which people try to cross more than once and get counted each time.

Between March 20, 2020, and February 4, 2021, the recidivism rate has soared to 38%, according to CBP’s estimates. By comparison, in fiscal year 2019 – October 1, 2018 through September 30, 2019 – the recidivism rate had fallen to 7% after years of decline. (The rate for fiscal year 2020 is unavailable.)

High recidivism means the number of encounters in the past year has included many of the same people, making the increase in encounters appear higher than it truly is.

It is also important to keep trends in mind.

For example, after a big drop in April 2020, encounters began steadily rising in June and have hovered above the 71,000 mark since October. The increase includes those attempting multiple crossings, and also those escaping from the growing struggles in their home countries.

Persistent poverty and persecution continue to be the main driver of migration from many countries in Latin America and elsewhere. But 2020 saw the pandemic and two hurricanes, which displaced more than half a million in Central America.

Kids trying to cross

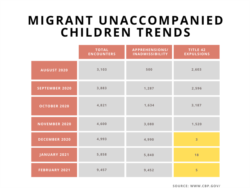

In his letter to Biden, McCarthy correctly said apprehensions of unaccompanied children were up in January. But his numbers don’t jibe with the official CBP figures, which would put the increase at only 90%, not 113%, as McCarthy claimed. (McCarthy’s office did not respond to questions for this fact-check.)

Overall, the CBP says nearly 30,000 unaccompanied minors have showed up at the border since October of 2020. Between January and February alone, apprehensions of unaccompanied minors spiked from 5,858 to 9,457 – a 61.4% increase.

In part, this is explained by a federal judge’s order in November requiring the Trump administration to stop turning back unaccompanied minors under the Title 42 pandemic policy. Although Biden has continued expelling adults under the policy, the administration said in February it would exempt unaccompanied children. As the numbers grow, the Federal Emergency Management Agency has been tasked to help shelter and process the unaccompanied minors.

The Biden administration concedes that it is struggling to deal with the problem.

“We are encountering six- and seven-year-old children, for example, arriving at our border without an adult,” Mayorkas said in a March 16 statement after McCarthy traveled to the Texas border to showcase the issue the prior day. “In more than 80 percent of cases, the child has a family member in the United States. In more than 40 percent of cases, that family member is a parent or legal guardian. These are children being reunited with their families who will care for them.”

Speaking to reporters in El Paso, McCarthy said: “It didn’t have to happen. This crisis is created by the presidential policies of this new administration. There’s no other way to claim it than a Biden border crisis.”

Biden’s decision to continue rejecting adults earned the wrath of immigrant advocates and even 60 fellow Democrats who urged Mayorkas to end the expulsions. The administration has tried to downplay the rising encounters, blaming Trump for leaving a broken system in place.

Stuck in Mexico

Overall, experts and immigrant advocates say most of those trying to approach the border now are people who under Trump policies have been stranded in Mexico for years.

In the summer of 2019, for example, Mexico agreed, under the Trump administration’s “Remain in Mexico” policy (known formally as Migrant Protection Protocols, or MPP), to require asylum seekers to wait in Mexico, instead of in the United States, for U.S. immigration proceedings.

Until January 2021, more than 71,000 people were returned to Mexico under MPP, according to Syracuse University's TRAC Immigration data tracker. Some 25,000 individuals in the program still have active cases.

On his first day in office, Biden directed the CBP to stop placing people into the program, and the administration announced in early February that it would start to gradually process them. To date, 1,500 individuals under MPP have been able to cross into the United States.

–

Editor's Note: Polygraph.info also recently fact-checked border statistics cited by President Joe Biden, a Democrat.