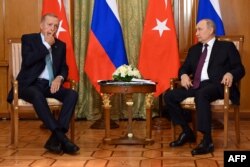

Following talks with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan on September 4, Russian President Vladimir Putin declined to renew Moscow’s participation in a deal that allowed Ukraine to export grain from its Black Sea ports, helping avert global food insecurity.

“Not a single obligation to Russia was fulfilled” under the deal, Putin claimed, accusing Ukraine of using the grain corridor to commit acts of terror.

“And while Russia clearly provided security guarantees for shipping under this deal, the other side used humanitarian corridors for terrorist attacks against Russian civilian and military facilities. This could no longer be tolerated,” Putin said.

That is false.

There is no evidence Ukraine has ever launched strikes from the grain corridor or used the designated humanitarian sea route for any military purpose. Russia’s Black Sea fleet, on the other hand, has systematically fired cruise missiles at civilian targets in Ukraine.

The grain corridor charted a very specific path and cannot be conflated with the entire Black Sea.

The 179-nautical-kilometer long, nearly five-nautical-kilometer wide humanitarian route ran to and from the Ukrainian ports of Chornomorsk, Odesa and Yuzhny/Pivdennyi to the Turkish Straits.

Vessels authorized to move in the corridor were required to remain on the route or in specified holding areas off the Ukrainian and Turkish coastlines.

The Joint Coordination Center (JCC), which was established to facilitate implementation of the grain deal and consisted of senior representatives from Turkey, Russia, Ukraine and the United Nations, monitored shipping in the corridor “using terrestrial and satellite means.”

Russia withdrew from the grain deal in July, with Putin falsely arguing that the agreement “did not justify its humanitarian purpose” and had “lost its meaning.”

Since then, Russia has systematically targeted Ukraine’s food-exporting ports.

Rosemary DiCarlo, United Nations undersecretary-general for political and peacebuilding affairs, condemned Russia for these attacks, saying they risk “far-reaching impacts on global food security, particularly in developing countries.”

Russia had suspended participation in the deal in October 2022, citing security concerns for civilian ships after Ukrainian drone attacks on the Black Sea fleet at Sevastopol, the largest city in Crimea. Russia framed those strikes as terrorist attacks.

Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba noted at that time Russia had used the strikes as a “false pretext” to suspend the deal, noting the strikes occurred 220 kilometers from the grain corridor route.

Shortly before pulling out of the deal in July, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Vershinin also accused Ukraine, without evidence, of using the grain corridor to carry out terrorist attacks.

"It was the Crimean Bridge, twice already; it was Sevastopol, remember last October,” Vershinin said.

But the Kerch Bridge is located hundreds of kilometers to the east of Sevastopol, while the grain corridor lies west of the Kerch Bridge and Sevastopol.

As previously reported by Polygraph.info, Moscow claims that the Kerch Bridge, a key artery for Russia in transferring combat vehicles, artillery, ammunition, fuel and personnel to the battlefield in Ukraine, is a strictly civilian target.

Ukrainian government officials argue that since Moscow uses the bridge as “a logistical route” for the Russian army, it is a legitimate military target for Ukrainian forces.

Ukraine and the United States have also credibly accused Russia of using its Black Sea fleet to strike civilian targets with sea-based Kalibr cruise missiles.

Russia’s Black Sea fleet can also be employed to support Russian ground forces in occupied Ukrainian territory, making it a legitimate military target.

After Russia began bombarding Ukrainian ports, killing civilians and destroying grain, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, accused Moscow of “waging war on the world’s food supply.”

Greenfield said that Russia, by weaponizing food, is “using the Black Sea as blackmail, holding humanity hostage.”

In an analysis published in July, Tom Dannenbaum, an associate professor of international law at Tufts University's Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, argued that if Russia, in order to secure sanctions relief, is intentionally preventing deliveries of food to populations who are not party to the conflict, that should “qualify as using food deprivation as a method of warfare.”

According to the JCC, nearly 33 million tons of grain and other food products were exported under the deal.

Approximately 57% of those shipments went to developing countries.

In July, Abraham Korir Sing'Oei, the principal secretary of foreign affairs in Kenya’s Ministry of Foreign and Diaspora Affairs, tweeted that Moscow’s grain deal pullout “is a stab on the back at global food security prices and disproportionately impacts countries in the Horn of Africa already impacted by drought.”