On May 23, Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro announced via Twitter that 1.3 million COVID-19 vaccine doses had arrived from China. He did not say exactly when they landed.

“[A]fter the arrival of 1,300,000 vaccines from China, a new phase in immunization against the Pandemic begins. We will complete care for health workers, education [workers] and patients with diseases that increase their vulnerability,” Maduro wrote.

But how that will happen is far from clear. So far, Venezuela’s vaccination efforts have lacked transparency, and the country has struggled to secure doses for even its most vulnerable population. Mixed messages from the government haven’t helped.

It is unclear exactly how many vaccine doses the government has secured. At the end of 2020, Maduro said the government had “guaranteed more than 10m doses of vaccines for the first quarter of next year,” the Financial Times reported.

Venezuela’s El Nacional newspaper said Maduro announced in late April that 930,000 vaccine doses had arrived. However, a day later, Health Minister Carlos Alvarado said the number was 1.48 million. Alvarado did not specify how many came from China or Russia, Venezuela’s two suppliers, or when they had arrived.

Maduro’s announcement about China vaccines came just days after the president of Venezuela's National Academy of Medicine said that, given the country’s slow rate of COVID-19 vaccination, it could take up to 10 years to inoculate the whole population.

Julio Castro, an infectious disease expert who advises Venezuelan opposition political forces on health issues, tweeted on May 24 that “what [the government calls] the ‘new vaccination phase’ is what should be happening in a week from now until the end of the year (one million weekly vaccinations) to reach the necessary goal.”

According to Our World in Data, as of May 25 only 316,000 COVID-19 vaccination doses had been administered in Venezuela. However, the site noted: “[D]ata for this location shows the number of vaccine doses given to people, not the number of people fully vaccinated. Since some vaccines require more than 1 dose, the number of fully vaccinated people is likely lower.”

Venezuela has a population of about 30 million. The total number of doses administered equals 1.1 doses per 100 people. In comparison, neighboring South American nations like Brazil and Colombia are administering 30 doses per 100 people and 16.6 doses per 100 people, respectively. Brazil has a population of 211 million and Columbia 50 million.

Maduro said earlier in May that Venezuela was aiming to vaccinate 70 percent of its population by August, when single-dose Russian Sputnik Light vaccines are due to arrive. As Reuters noted: "There has been no announcement about whether or not some of those doses have already arrived.”

The National Academy of Medicine asked the U.S. this month to include the nation to its donor list of COVID-19 vaccines, “despite a political freeze between the two countries,” Reuters wrote.

“To control the pandemic in our country, we need to vaccinate around 70% of the adult population, nearly 15 million people, in as little time as possible … The amount of vaccines that have arrived to Venezuela ... represents less than 10% of what Venezuela needs,” the academy wrote in a statement.

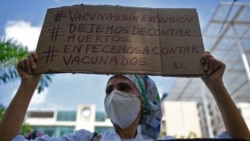

Equity in vaccine distribution has also been an issue. Last month, Venezuelan health care students protested in Caracas "demanding a national vaccination plan and 100% vaccination coverage for doctors and nurses," Reuters reported.

Bloomberg News reported on April 14 that Venezuela’s government was “restricting COVID-19 shots to people with a state loyalty card, effectively excluding many government opponents from getting vaccinated.”

The agency wrote that as Venezuela's elderly population began being vaccinated, recipients were selected “from a registry used by the Nicolas Maduro administration to keep tabs on voter loyalty and grant state subsidies.”

To date, Venezuela has officially reported more than 226,000 COVID-19 cases and more than 2,500 deaths from the disease. But Dr. Enrique Lopez-Loyo, president of the country's Academy of Medicine, told Reuters that independent specialists and international studies say those numbers “should be multiplied by eight or 10 due to the country’s low test rate.”