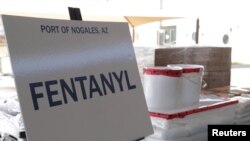

On April 14, the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned two Chinese companies and four Chinese nationals for allegedly supplying Mexican drug cartels with precursor chemicals to produce illicit fentanyl intended for U.S. markets.

In response, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin said on April 17 that the U.S. sanctions had “seriously eroded” bilateral anti-drug cooperation and that the U.S. had itself to blame for the fentanyl abuse crisis, which has killed tens of thousands of Americans annually since 2016:

“Guided by the humanitarian spirit, we have worked with the U.S. to help solve its fentanyl abuse as much as possible,” he said. (It should be noted that the ministry omitted “as much as possible” in its English translation of the news briefing.)

That is misleading.

China, which is the world’s biggest supplier of fentanyl precursor chemicals, links counternarcotics cooperation with the United States with China's broader geostrategic relations.

While Chinese cooperation with the United States on curbing the supply of fentanyl has yielded some successes, Beijing has backed away from bilateral anti-drug cooperation with Washington since 2019. On August 5, 2022, China formally suspended its counternarcotics cooperation with the U.S. after House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan, the democratically self-ruled island that Beijing claims as its own.

Here is some background on the fentanyl crisis in the U.S. and China’s role in it.

Fentanyl, a prescription drug in the U.S., is a potent synthetic opioid used medically as a painkiller and anesthetic.

However, there is also illicitly manufactured fentanyl, which is “often added to other drugs because of its extreme potency, which makes drugs cheaper, more powerful, more addictive, and more dangerous,” according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Illicit fentanyl is sold through illegal drug markets and “often mixed with heroin and/or cocaine as a combination product—with or without the user’s knowledge—to increase its euphoric effects,” says the CDC.

According to the CDC, fentanyl is up to 50 times more potent than heroin.

“Illicit fentanyl is responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of Americans each year,” said Brian Nelson, U.S. Under Secretary of the Treasury for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, fentanyl is now the leading cause of death of Americans aged 18 to 49.

“Between 2019 and 2021, fatal overdoses increased by approximately 94%, with an estimated 196 Americans dying each day from fentanyl,” says the DOJ.

Most recent fentanyl-related overdose cases are linked to illicitly manufactured fentanyl, according to the CDC.

China was “the primary source of U.S.-bound illicit fentanyl, fentanyl-related substances, and production equipment” before 2019, when Chinese traffickers supplied fentanyl and its variants directly to the United States via international mail and express consignment operations, according to the Congressional Research Service.

After years of U.S. diplomacy, Chinese President Xi Jinping agreed to tighten regulations over fentanyl drugs during the December 2018 G-20 summit. China subsequently passed new laws, effective May 1, 2019, putting all fentanyl-related substances under national control.

As a result, “the direct shipment of fentanyl and fentanyl-related substances from China to the United States went down to almost zero,” Kemp Chester, a senior adviser in the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, testified to the U.S. Senate in July 2022.

Mexican transnational criminal organizations—mainly the Sinaloa Cartel and the Jalisco Cartel and their affiliates, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)—have since been predominantly responsible for the production and distribution of U.S.-consumed illicit fentanyl.

However, the fentanyl precursors the cartels use to produce illicit fentanyl are almost entirely sourced from China, with a much smaller amount from India.

“The cartels are buying precursor chemicals in the People’s Republic of China (PRC); transporting the precursor chemicals from the PRC to Mexico; using the precursor chemicals to mass produce fentanyl; pressing the fentanyl into fake prescription pills; and using cars, trucks, and other routes to transport the drugs from Mexico into the United States for distribution,” DEA administrator Anne Milgram testified during a U.S. Senate hearing in February.

Some of the precursor chemicals for producing fentanyl are not internationally controlled and are legal to produce in China and export from the country. Beijing thus claims it cannot stem the export of precursors that aren’t illegal.

However, Vanda Felbab-Brown of the Brookings Institution, a Washington-based think tank, argued that Beijing could track shipments of those precursors much more closely if it chose to, “considering some Chinese companies are clearly marketing their products to the cartels,” U.S. news site Axios reported.

The United States has called on China to adopt “know-your-customer” procedures, such as customer identification and verification, for precursor chemicals shipments, to ensure that they are not sold to likely drug traffickers, and to alert authorities about such buyers.

In September 2022, then Chinese Ambassador to the United States Qin Gang appeared to rule out the “know-your-customer” approach, telling Newsweek magazine that such a protocol “far exceeds U.N. obligations.”

In testimony submitted to the U.S. House of Representatives Subcommittee on National Security, Illicit Finance, and International Financial Institutions on March 23, Brookings’ Felbab-Brown noted that Chinese actors “have come to play an increasing role in laundering money for Mexican cartels.”

The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, citing the DEA, reported in 2021 that U.S. law enforcement had seen “a growing trend of Chinese nationals, in both Mexico and the United States, working with Mexican cartels.”

In November 2018, U.S. authorities arrested Xianbing Gan, a Chinese national based in Chicago, on suspicion of money laundering for a Mexican drug cartel. He was convicted in March 2020. In October 2019, U.S. authorities charged three Chinese nationals with money laundering for Mexican drug traffickers. In September 2020, a U.S. court convicted Chinese national Xueyong Wu for laundering money for a Mexican drug cartel and sentenced him to five years in prison.

U.S. officials have previously highlighted successes in U.S.-China antinarcotics cooperation, including a Chinese court in Hebei sentencing nine defendants in 2019 for trafficking fentanyl to the United States.

However, even prior to China’s formal suspension of bilateral anti-drug cooperation, U.S. authorities noted “significant gaps” in the cooperation, “especially in enforcement and criminal prosecution.”

Felbab-Brown said in her U.S. congressional testimony that “China has become a black hole for visibility into its internal law enforcement actions.”

After the U.S. in May 2020 placed export controls on an institute controlled by China’s Ministry of Public Security (MPS), citing the ministry’s role in human rights violations in Xinjiang, China contended that those export controls “seriously affected” the examination and identification of fentanyl substances performed by the MPS-led National Narcotics Laboratory and “greatly affected China’s goodwill to help the U.S. in fighting drugs.”

According to the Congressional Research Service, China has not reported taking action to control 4-AP, boc-4-AP, and norfentanyl, three fentanyl precursors that the United Nations added to its list of fentanyl-related substances subject to international control in March 2022. In addition, Chinese nationals indicted in the United States on fentanyl trafficking charges remain at large.

The U.S. State Department said in its 2022 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report that China “does not cooperate sufficiently on financial investigations and does not provide adequate responses to requests for information.”