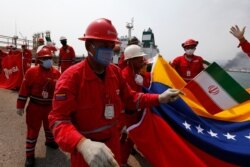

The arrival in Venezuela of five Iranian oil tankers is expected to ease the South American nation’s gasoline crisis, while challenging U.S. sanctions targeting both countries.

The Iranian fuel tankers began arriving in Venezuela last week under the protection of Venezuelan military forces, with the fifth cargo reportedly arriving on Sunday.

Venezuela’s oil sector has been acutely damaged by years of political and economic instability. Iran says the fuel shipment provided to Venezuela is about 1.53 million barrels of gasoline and petrochemical components.

U.S. sanctions imposed on Venezuelan state-owned oil company PDVSA also have crippled Venezuela’s ability to import certain types of fuel from abroad, but the government of President Nicolas Maduro has turned to Iran for refining parts and fuel.

On Saturday, Venezuelan officials announced that the Iranian gasoline has arrived at hundreds of gas station across the country.

“Venezuela has the right to buy in the world whatever it wants to buy,” Maduro said in a recent speech. “Fortunately, Venezuela has more friends than what people can imagine.”

Defying Washington

Iran and Venezuela are under U.S. economic sanctions, which has brought the two countries closer economically and politically.

“Iran and Venezuela have always supported each other in times of difficulty,” Venezuelan foreign minister Jorge Arreaza said in a tweet last week, adding that, “Today we see the fruits of the multipolar world, of our Bolivarian Diplomacy for Peace and South-South Cooperation.”

The South-South cooperation refers to the technical cooperation among developing countries in the Global South, including the sharing of skills and resources.

Some experts believe that the Iranian move to transport oil to Venezuela is a show of defiance against the U.S. by the two allies.

“This move is very significant,” said Alireza Mehrabi, a political analyst in Tehran. “It sends a message that U.S. hegemony is nose-diving, and countries of the South should strengthen their relations and circumvent threats and sanctions imposed by Washington through building strategic ties.”

Other Iranian experts, however, say that this dominant narrative propagated by the Iranian government could send mixed signals.

“This sends a signal that [U.S. President Donald] Trump’s maximum pressure policy on Tehran has been effective so much so that Iran is willing to take grave risks to sell its oil (products) to Venezuela under a very uncertain barter deal,” said Mehdi Mottaharnia, a Tehran-based international affairs analyst.

US pressure

U.S. officials said the United States was applying pressure to deter Iran and Venezuela from carrying out the oil transfer, while also warning foreign governments, seaports, shipping companies and insurers that they could face U.S. sanctions if they assist the tanker fleet.

“We’ve alerted the shipping community around the world, ship owners, ship captains, ship insurers, and we’ve alerted ports along the way between Iran and Venezuela,” Elliott Abrams, U.S. special representative on Venezuela, told Reuters Friday.

Earlier in May, the U.S. issued a global maritime advisory, giving guidance to the shipping industry on how to avoid sanctions related to Iran, North Korea and Syria.

But Iranian President Hassan Rouhani warned last week that any U.S. intervention against Iranian oil tankers bound to Venezuela would be met with retaliation.

“Any pirate-like action by the U.S. Navy against the Iranian fuel shipments to Venezuela would trigger a harsh response,” Rouhani was quoted as saying by pro-Iranian government Nour News Agency.

No desire for conflict

Observers believe that Washington has no desire to start a conflict with Venezuela over a fuel shortage that could be seen “a humanitarian crisis.”

“Under the circumstances, the passing of the tankers can be interpreted as a weakness for the United States,” said José Toro Hardy, a prominent Venezuelan economist and a former director of the country’s PDVSA.

“But I thought for humanitarian reasons, (the Americans) were going to let the tankers pass. I also thought that they could have stopped some of the tankers to guarantee if the only thing they brought was gasoline, because it has also been said that (Iranian tankers) could bring other things,” he told VOA.

“I believe that any action the U.S. takes or has been taking in the form of sanctions, is taken when the U.S. is interested to do so,” Hardy added.

Washington backs Maduro’s rival Juan Guaido and considers him as Venezuela’s legitimate leader following a presidential crisis in January 2019.

Yousof Azizi, a research assistant at the Virginia Tech university, says while this oil transaction between Iran and Venezuela “is not significant and plays no major role in Iran’s sanction-stricken economy,” it could have a political motive behind it.

“Tehran has meticulously evaluated the U.S. political climate in the months leading to the (presidential) election and decided to challenge Washington, reckoning that no response should be expected from Washington despite pressure from ‘Hawks’ within the incumbent administration,” he told VOA.

Azizi noted that the U.S. hasn’t decided to take any immediate action against Iran, “partly due to the fact that the U.S. is aware that escalating tensions would not be beneficial to Trump’s bid for a second term.”

Workforce shortage

The supply reportedly will help Venezuelans authorities expand retail sales of gasoline under a system combining subsidies and international prices.

“Iran has sent additives, in this case alkylate, one of the components necessary to refine gasoline,” said Ivan Freitas, leader of the Unitary Federation for Oil Workers in Venezuela.

“Iran assumes that Venezuela can obtain the other components on its own to restart the refineries. But even if this is the case, the conditions in which these plants find themselves, four in total in the country, are very bad,” he told VOA.

But Freitas noted that Venezuela faces a massive shortage of qualified oil workers capable of operating oil refineries.

Qualified workers have left Venezuela. Only 2 or 3% of qualified (workers) have remained,” he said, adding that if the Venezuelan government “put a plant into service, it would be a lottery to know for how long it will work. There will be no operational stability. In these conditions, the refineries are of high risk.”

Gold payment

Some experts say that given Venezuela’s deteriorating economy and following the departure of Russian oil company Rosneft from the country, Caracas will likely pay Iran in gold for its fuel supply.

“It looks like the only way [Venezuela)] can pay is with gold. Simply because Venezuela’s oil production has declined, and oil represented 97% of Venezuela's foreign exchange earnings,” economist Hardy said.

He added that “there is no foreign exchange income. The other foreign exchange income was through the remittances of the more than 5 million Venezuelans who have left and were sending money to their families, but during the COVID-19 pandemic that has been abruptly interrupted.

“The only alternative that Venezuela could have that interests Iran in economic terms is gold,” Hardy concluded.

Some information in this report came from Reuters.