From the brutal killings of U.S. freelancers James Foley and Steven Sotloff in Syria in 2014 to the deaths in Libya 10 years ago this week of photojournalists Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, the Arab Spring has had a devasting toll on the media community.

It also has had a huge impact on the way news organizations and journalists think about coverage in conflict zones, with tangible changes to how news outlets prepare staff and freelancers.

The deaths of Hetherington and Hondros, who were hit by shrapnel from a mortar blast on April 20, 2011, led to a focus on first aid. Colleagues of Hetherington set up the organization RISC in his memory, to provide battlefield medical training to freelancers.

But it was the horrific actions by the Islamic State militant group in 2014 that had perhaps the biggest impact. Videos, shared widely on social media, showed the militants killing journalists and others taken hostage in Syria.

It was an incident that left editors and news executives scrambling for ways to keep journalists safe in conflict zones.

Decision on Syrian coverage

One of the first steps was the suspension of dispatching journalists to countries such as Syria, which was at the peak of its civil war.

"When the AP made the decision that going into contested areas of Syria had become too dangerous for any staff, it also made a principled decision to not commission or accept work from freelancers," said John Daniszewski, the vice president for standards and editor at large at The Associated Press.

"We felt we should not be encouraging freelancers, even indirectly, to do work that we felt was too dangerous," he told VOA.

Syria is one of several countries that experienced a popular uprising in the early months of 2011. Known as the Arab Spring, a protest movement that started in Tunisia spread quickly to Egypt, Libya, Syria and Yemen.

A decade later, many of these countries are among the world's most dangerous for media, as protests have descended into civil war and rival militias and newly installed authoritarian leaders now target journalists.

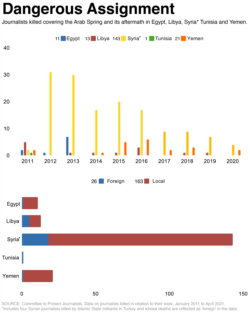

In total, 189 journalists from those five countries were killed either covering the initial protests or reporting on the resulting unrest and conflict that persisted for the past 10 years, according to data by the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Frontline safety

In response to the violence, news organizations and media groups, including the AP and Reuters, formed A Culture of Safety Alliance, or ACOS Alliance.

"What we saw around the Arab Spring, and really the climax of it was the beheadings of Foley and Sotloff, was definitely a change in the media landscape," said Maria Salazar-Ferro, president of ACOS Alliance and director of emergencies at CPJ.

"We're talking about two young freelancers who were in a conflict area without the traditional support a staff journalist would have originally had," Salazar-Ferro said.

The Arab Spring saw an increase in freelancers, some unprepared, going into high-risk situations at a time when newsrooms around the world were shrinking and had fewer resources to send in staff.

For U.S freelancer Anna Therese Day, the Arab Spring kick-started her career as she traveled to Bahrain to cover the 2011 protests.

"It was cheaper [for news outlets] to work with people on the ground, and it presented a lot of opportunity for international and local freelancers to get a foothold in the news," she told VOA. "I was a young reporter and I kind of seized that opportunity."

But, she said, "news organizations were extremely ill-equipped to deal with the rapidly escalating threats that we were facing."

The experience led Day and others to form the Frontline Freelance Register in 2013— to "keep each other safe."

The register is now part of the ACOS Alliance, which works to resolve some of those issues by creating best practices for freelance journalists and the outlets using them.

From the company side, said AP's Daniszewski, who is on the ACOS board, those principles stress treating freelancers as equivalent to staff in terms of risk assessment, training and supervision — and aid if the journalist is captured or harmed on assignment.

"From the freelancers' side, it emphasized that the freelancer had an obligation to obtain protective gear, hostile environment training and some kind of insurance coverage," Daniszewski said.

Day, a 2020 James Foley World Press Freedom awardee, has firsthand experience of the importance of risk assessments. She and three colleagues were arrested in Bahrain in 2016 while covering the fifth anniversary of the uprising.

Authorities separated the journalists and interrogated them, Day said, trying to get names of sources. "It escalated in a pretty scary way, but fortunately the solidarity work and the community immediately activated," she told VOA. "We were actually extremely prepared for what would happen."

Access for all

Of the 189 journalists killed covering the Arab Spring since 2011, 163 were local, CPJ data show. To try to address that, ACOS expanded its program to include local media.

One of its regional partners, the Beirut-based Samir Kassir Foundation, has been instrumental in implementing safety programs.

"We don't necessarily limit the idea of general security to being only in a war zone," said Ayman Mhanna, executive director of the foundation.

"We are living in countries where riot police are acting in a very harsh way, where civil troubles and demonstrations might turn very negatively, and where there is use of tear gas and other aspects related to the security that journalists need to take into account," he told VOA.

For these groups, the ultimate objective is to change the culture among journalists, editors and newsrooms.

"We think that you have to approach it from every angle that you can and make sure that everyone had access to that information, to that change in thinking about safety, so that conversation can continue, whether you're an editor in New York or you're a local journalist who's working in Lebanon or an international photographer who's just flown into Iraq," Salazar-Ferro, of CPJ, said.

The programs appear to be having an impact, with an increase in the use of risk assessments and a "thirst for more information, for better resources," she said.