WASHINGTON —

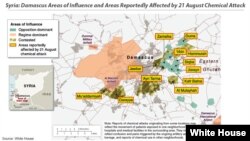

The United States is weighing military action against Syria for its alleged chemical weapons attack on rebel forces and civilians outside Damascus on August 21.

U.S. officials say President Barack Obama is considering limited military action to deter and degrade the Syrian government’s ability to use chemical weapons.

Christopher Hill, former U.S. ambassador to Iraq and special envoy to Kosovo (1996-1999), says the reason given by the Obama administration resembles the one used in 1999 when NATO launched a bombing campaign to degrade the Serbian military forces and stop ethnic cleansing in Kosovo.

But Hill says there is a fundamental difference between the situation in Syria and Kosovo: the Kosovo campaign was part of an overall political plan for the Balkan region.

"With respect to Syria, there is no political process," he said. "There is no way forward, there has been no agreement on what Syria should be in the future, what kind of governance it should have in the future. And so we are in a situation where there’s going to be a use of force, but it is in respect not so much of the Syrian situation, but in respect of the use of banned weapons, weapons that have been banned for 100 years."

Retired United States Marine Corps General Anthony Zinni, who headed "Operation Desert Fox" — a series of air strikes against Iraq in December 1998 — agrees.

"We don’t have a strategy. We are reacting to a single event," he said. "We are trying to isolate it from the overall conflict, and it can’t be.

"You are about to do something that in effect is an act of war," he added. "You are about to take sides. Although the president has tried to make the intellectual argument [that] this is about a non-acceptable violation of international norms and use of chemical weapons, it still means you are attacking one element there.”

Zinni says a U.S. military strike on Syria will not be seen only as an attack on President Bashar al-Assad.

"This will be taken in the region that you are attacking Alawites, Shia, Christians," he said. "The tribal, ethnic and religious sects here are so divided, that once you do something — regardless of intention — you have in effect taken a side."

Zinni and Hill say that in previous wars — whether in Iraq, Afghanistan or Libya — the United States was able to put together an international coalition in advance of planned strikes.

"What has happened that should not have happened is we should have gained international support and commitment to act well before this and not wait to the last minute to try to put it together," said Zinni. "But to try to scramble to put a coalition together at the last minute, to gain international legitimacy: it creates a problem once you have moved assets into position and said that this is the crossing of the red line."

The United States lost a major partner in a potential international coalition strike against Damascus when British parliamentarians on Thursday voted to keep their armed forces from out of any military action against Syria.

U.S. officials say President Barack Obama is considering limited military action to deter and degrade the Syrian government’s ability to use chemical weapons.

Christopher Hill, former U.S. ambassador to Iraq and special envoy to Kosovo (1996-1999), says the reason given by the Obama administration resembles the one used in 1999 when NATO launched a bombing campaign to degrade the Serbian military forces and stop ethnic cleansing in Kosovo.

But Hill says there is a fundamental difference between the situation in Syria and Kosovo: the Kosovo campaign was part of an overall political plan for the Balkan region.

"With respect to Syria, there is no political process," he said. "There is no way forward, there has been no agreement on what Syria should be in the future, what kind of governance it should have in the future. And so we are in a situation where there’s going to be a use of force, but it is in respect not so much of the Syrian situation, but in respect of the use of banned weapons, weapons that have been banned for 100 years."

Retired United States Marine Corps General Anthony Zinni, who headed "Operation Desert Fox" — a series of air strikes against Iraq in December 1998 — agrees.

"We don’t have a strategy. We are reacting to a single event," he said. "We are trying to isolate it from the overall conflict, and it can’t be.

"You are about to do something that in effect is an act of war," he added. "You are about to take sides. Although the president has tried to make the intellectual argument [that] this is about a non-acceptable violation of international norms and use of chemical weapons, it still means you are attacking one element there.”

Zinni says a U.S. military strike on Syria will not be seen only as an attack on President Bashar al-Assad.

"This will be taken in the region that you are attacking Alawites, Shia, Christians," he said. "The tribal, ethnic and religious sects here are so divided, that once you do something — regardless of intention — you have in effect taken a side."

Zinni and Hill say that in previous wars — whether in Iraq, Afghanistan or Libya — the United States was able to put together an international coalition in advance of planned strikes.

"What has happened that should not have happened is we should have gained international support and commitment to act well before this and not wait to the last minute to try to put it together," said Zinni. "But to try to scramble to put a coalition together at the last minute, to gain international legitimacy: it creates a problem once you have moved assets into position and said that this is the crossing of the red line."

The United States lost a major partner in a potential international coalition strike against Damascus when British parliamentarians on Thursday voted to keep their armed forces from out of any military action against Syria.