For 50 years, beginning in 1916, African American photographer James VanDerZee photographed the middle class and elite of Harlem, the historically black section of Manhattan: in their wedding portraits, reading in their parlors, sitting under their Christmas trees.

Many of his silvery studio portraits and occasional street scenes of Manhattan's historically black section are archived at the neighborhood's Studio Museum. Taken together, the images serve as a jumping-off point for its annual high school photography program, “Expanding the Walls.”

“I liked his style, the dreamy contrast feel, how deep the darks are and how light the whites are, and I tried to be inspired by that,” said Gabriella Rosen, one of 16 students annually chosen from dozens of applicants.

Participants receive cameras and a stipend to study under working artists, and they also make frequent studio visits and sometimes lead discussions with visitors to the Studio Museum, which is dedicated to work by artists of African descent.

Rosen’s own red-tinged, noir-ish images — participants' works are included in a final exhibition — explore her fascination with superheroes, she says.

In one photograph, a figure crouches beside a body in a hallway, an image whose ambiguity Rosen calls intentional.

"I wanted to define the line between good and bad in the life of a superhero, so-called, and how in order to be good you have to have something bad happen - or do something bad," she said.

On an opposite wall, a 1929 VanDerZee photograph depicts a different kind of superhero: a regal-looking man with a great mane of white hair sits deep in thought. He’s wearing a suit, and his surroundings are elegant, but his feet are bare.

Gerald Leavell, the program's coordinator, says the “Barefoot Prophet,” as he was known, was a street preacher by the name of Elder Clayhorn Martin.

“He’s a very big man, with a lot of presence. He said that God spoke to him and told him that he should remove his shoes and walk barefoot and preach the Gospel," Leavell said. "And that’s what he did,” even in winter.

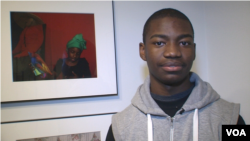

“Before the program, I didn’t think culture and art were important,” said Max Desmarais, who took part in the 2013 program and is now working on a short documentary film.

“It showed me more about the world, more about myself, made me more open-minded,” he added, explaining that VanDerZee “showed how black people, African Americans, were classy. I think there should be more images like that.”

Photographs by another student participant, Jesus Morales, have an otherworldly feeling. “When You Are Engulfed in Foliage” shows a young woman sitting in front of a window, a projection of green fronds on her face.

“I was just dealing with the technicality of a portrait, and also I really like Wes Anderson and Gregory Crewdson, so I wanted to copy them, because I love them so much,” said Morales, who is contemplating a career in photography.

A striking photograph by Christopher Neal shows two youths with their heads covered in blue paper.

“I was going through a time in school where I felt students didn’t have enough of a voice,” he said. “I used this to show the silence of youth, and not being able to communicate ideas to authority or anyone else around you.”

His other photograph is of a young girl in a green head wrap, seemingly testifying or praying beside a headless mannequin in front of a blood red wall.

“That one is about freedom of ideas,” he said.

The student show at The Studio Museum in Harlem will be on display through October 26.