Growing up in a religious family in Pakistan, exiled journalist Taha Siddiqui wasn’t allowed comic books.

“My father was very religious,” Siddiqui told VOA, adding that his father believed that comic books and any drawings of the human body were "not allowed in Islam.”

But now the journalist, who has been living in Paris since 2018, is using that medium to tell his story of surviving an attempted kidnapping and other threats.

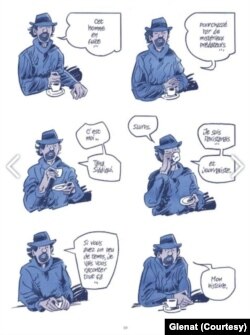

Released in France in March, Dissident Club is a comic book-style autobiography. And Siddiqui sees publishing it as an act of resistance.

"Comic-, graphic-style book writing is very common and popular throughout Europe, including France,” said Siddiqui. “So, my author friends suggested that I should write something in [that] style.”

Comics are a new venture for Siddiqui. When he lived in Pakistan he worked as a reporter with several international media outlets.

It’s work that earned him recognition, including the Albert Londres Prize in 2014 for his reporting on the dangers for health workers supplying polio vaccines in areas vulnerable to extremist groups.

The dramatic end to his journalism career in Pakistan is the start to Dissident Club.

"On January 10, 2018, I was going to Islamabad Airport when unknown armed men tried to kidnap me, but I managed to escape,” he told VOA.

The journalist was pulled from a taxi into a different car. Fortunately he was able to see an unlocked door and escaped the moving vehicle.

He believes he was targeted for his criticism of the Pakistani military, including his reporting for The New York Times exposing secret prisons.

Pakistani government and security agencies have denied allegations that state agencies are involved in enforced disappearances.

Siddiqui filed a first information report — the initial step in filing a police complaint — and was offered police protection.

But he said, "My friends from the media and my family advised me to leave the country, so I finally came to France with my wife and 4½-year-old child.”

The graphic novel also covers issues of extremism in the region, as viewed through Siddiqui’s upbringing, and details the period of 9/11, when Siddiqui returned to Pakistan from Saudi Arabia, and eventually became a journalist.

"This is my own story, but it is also the story of what was happening in the society at that time,” he said.

When he started reporting for foreign media, Siddiqui says that the media wing of the Pakistan Army, known as the ISPR, “started harassing and threatening me.”

A legal complaint was also filed against him under Pakistan’s Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act.

“Asma Jahangir was my lawyer for that case, I have shown in the book how she helped me,” Siddiqui said.

The book also describes how his life in Pakistan gradually became difficult after the 2018 attack and how the circumstances forced him to leave the country.

The ISPR did not respond to VOA’s email request for comment.

Life outside Pakistan

Even in exile Siddiqui says he did not find complete safety.

American authorities contacted the journalist in late 2018 to say that his name was on a "kill list" and that if he ever went to Pakistan, he would be in danger. The French authorities also contacted him with the same information the following January.

"Many people ask me that you left Pakistan, you must have been safe. This is not true. There are many Pakistanis in exile who have had faced such disturbing incidents,” he said. “I still receive threatening phone calls, people coming to my workplace and harassing me. ... My family members are still being harassed in Pakistan.”

Such threats are common for journalists in and outside of Pakistan, according to Reporters Without Borders (RSF), whose annually updated Press Freedom Index ranks Pakistan 157 out of 180 countries, where 1 has the best environment for journalists.

Daniel Bastard, RSF’s Asia-Pacific director, says the effect on media is devastating, with journalists aware that they potentially risk their lives for their work.

“There has been a pattern in recent years, through which Pakistani journalists living abroad have been subject to intimidation and more,” Bastard said. “The most extreme case is that of Arshad Sharif of course, who was killed in Kenya after having to flee his own country.”

Sharif was shot by police in Kenya last year in what Kenyan authorities at the time say was a case of mistaken identity.

Pakistan has set up a commission to investigate Sharif’s death and the country’s information minister has repeatedly called for others to avoid speculation while that commission investigates the facts.

Speaking about the environment for media in the country, Bastard said, “It seems that some state agencies in Pakistan, who are already closely monitoring what journalists can and cannot write or say, are also trying to prevent voices from speaking up about subjects that are taboo in the Pakistan-based media.

“These agencies have absolutely no limitation regarding the respect for the rule of law and the sovereignty of the countries where journalists [move to],” he said.

VOA attempted to reach Marriyum Aurangzeb, the federal minister of information and broadcasting, for comment. One of her staff said that the minister was busy but would answer later. At the time of publication, VOA had not received a response to its text message.

Pakistani authorities have previously said that Islamabad values the role of independent media.

Exiles unite

When Siddiqui needed a title for his book, he found an idea close to his new home.

The book is named after his bar in Paris — the Dissident Club — that he opened for exiles like himself.

Russian, Chinese, Iranian, Ukrainian and Afghan political exiles and refugees, among others, come for intellectual, political and cultural activities.

“Sometimes exile can make you feel a little lonely, so the idea of the bar was to sort of create a space where I would have of course, financial stability, but also meet similar people with similar backgrounds so that I feel like I'm not the only one doing this,” said Siddiqui.

“It's a way to give meaning to my exile,” he added.

The journalist has also founded the website Safe Newsrooms, which focuses on media censorship in South Asia.

This story originated in VOA’s Urdu Service.