American artist Alexander Calder is best known for his enormous mobiles. His largest, from 1976, hangs in the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. However, another Washington museum, the National Portrait Gallery, is showing a different side of Calder.

Barbara Zabel curated the exhibition, "Calder’s Portraits: A New Language."

"He did so many mobiles, particularly late in life, that certainly the great proportion of his work are mobiles, stabiles," says Barbara Zabel, who curated the exhibition, "Calder’s Portraits: A New Language." "But at the same time he was working on those, he would be doing little portraits, drawings."

In fact, Calder was doing portraits long before he created a mobile.

"The earliest one in the show is 1907 when he was 9 years old," Zabel says. "It is after his parents provided him with his own studio or workshop."

According to Zabel, other self-portraits followed. "He really wanted to become a painter, like his mother, initially. But I think his love of materials led him to sculpture."

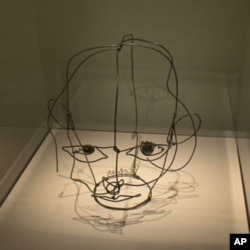

Calder’s three-dimensional portraits were unlike anything people had seen before. One critic described them as drawing in space.

Zabel says they grew out of the miniature circus he created in the 1920s and used in performances.

"The circus involved creating little figures out of wire and so out of this generated an interest in portraiture."

Sometimes, but not always, Calder would do a sketch first.

"Typically he would throw a whole roll of wire over his shoulder, and work with the end of it," says Zabel. "Then if he needed to stop something and go in another direction, he might snip it and start with a new piece."

In the exhibit, Calder’s portraits of celebrities are often placed alongside photographs from the Portrait Gallery’s collection, like those of baseball star Babe Ruth and entertainer Jimmy Durante.

Shadows cast by the sculptures were as important to the artist as the works themselves.

"He wanted to light them all himself. He referred to himself as an illumination engineer," says Zabel. "The portraits hanging from the ceiling also are in slow motion. You see the shadows move."

They were precursors to his famous mobiles. Later, Calder combined the two. A portrait of cartoonist Saul Steinberg seems to be followed by dark clouds.

"I think he felt he (Steinberg) was followed by doom and gloom everywhere he went and Calder tries to bring this out in a very humorous way," says Zabel.

The artist's last wire portrait was of himself, originally thought to be from the 1920s. His portraits are not as numerous as his abstract work, but Zabel says they reveal a side of the artist not frequently seen.

"What fueled his work in portraiture is a genuine attraction to other people."

In Calder’s portraits, we see a man who loved humanity as much as art.