A photography exhibit at the National Museum of Women in the Arts highlights the struggles and triumphs of women in the Arab world and Iran. Titled "Rawiya," Arabic for “she who tells a story,” the display encompasses the visions of 12 contemporary women photographers from Iran and the Arab world. Each of its 84 pieces tells a story and provides insight into social and political issues.

The exhibit has traveled to several U.S. museums over the past three years.

Gaza

Tanya Habjouqa spent two months in Gaza in 2009 to create a photo essay on the “Women of Gaza,” who live in the small, Palestinian territory that borders Israel, Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea. Gaza is extremely overcrowded, and people are not free to enter or leave the area due to an Israeli and Egyptian blockade.

Habjouqa documented the everyday life of Palestinian women, whom she said live in “oppressive conditions and struggle to maintain a normal life.” The photographer, a Jordanian-American, who now lives in Israel, told VOA that “the strongest people I met were the women.”

She also said one of her favorite photos is of women enjoying an outing with their family on the beach, sitting next to a yellow car. "The sea gave them a reprieve,” she said.

Habjouqa said it took time to earn the women's trust and get them to open up. She recalls the day she photographed a woman, completely veiled, sitting on a bench outside. The subject nodded to Habjouqa that it was OK to snap a picture of her with a teddy bear.

Yemen

Yemen’s first professional female photographer, Boushra Almutawakel, gained international recognition for using the hijab, the veil that covers a woman’s head, to challenge social trends and public appearance.

In one photo from her 2001 series “The Hijab,” a woman wears an American flag as a veil. Almutawakel said the picture asks whether you can be both a loyal Muslim and loyal American.

Almutawakel said it has stirred up a lot of reaction. Some Americans are offended because the woman’s head is covered by a U.S. flag, and some Muslims don’t like the flag being used as a hijab.

Iran

In Iran, photographer Gohar Dashti, has created photos about social issues by staging them at a government-owned area used by filmmakers who make movies about war. Her 2008 series, “Today’s Life and War,” represents the legacy of war and its effects on contemporary society. One haunting image shows a couple wearing wedding clothes, seated in a burned-out car on a battlefield, looking directly at the camera.

“Though they do not visibly express emotion, the man and woman embody the power of perseverance, determination and survival,” Dashti said.

Another Iranian photographer, Shadi Ghadirian, examines female identity, censorship and gender roles. Because she cannot photograph a woman’s hair or any physical contact between men and women, she uses humor and parody.

In her “Qajar” series, women pose in front of opulent backdrops reminiscent of the 19th century. One picture shows a woman dressed in a vintage Iranian costume wearing modern sunglasses.

The clothes in the portraits are more revealing than what is acceptable for Iranian women to wear in public today.

“I hope that when people see my photographs, they’ll understand the reality of women in Iran, then and now,” Ghadirian explained.

Newsha Tavokolian photographs female singers in Iran who are not allowed by Islamic law to sing solo in public or record their music. In her 2010 series “Listen,” she shows professional singers performing in front of an imaginary audience. Tavokolian also created a mock CD cover of a woman standing in the sea, “like a modern Venus,” she said. The album is titled “Don’t Forget This Is Not You.”

Morocco

Moroccan-born photographer Lalla Essaydi, who lives in New York, created “Bullets Revisited #3,” a three-panel piece of a woman lying down. The subject is covered with henna calligraphy and surrounded by bullet casings.The woman’s beauty and the bullet casings symbolize the violence and restrictions on women.

Egypt

Egyptian artist, Rana El Nemr captures urban images that question space, identity and the sense of belonging. In her 2003 series, “The Metro,” she discreetly photographs women in the Cairo subway's first cars of each train, reserved for women and children. In “Metro #7,” two women glimpsed through the windows convey the anonymity of city life. El Nemr sees them as “vulnerable to cycles of depression, indifference and religious tolerance.”

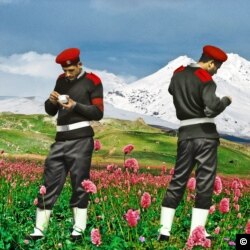

Nermine Hammam, who lives in Cairo, combines reality with fantasy in “Cairo Year One: Upekkha” by examining the Egyptian revolution in 2011 and its aftermath. She juxtaposes images of young, vulnerable soldiers in Tahrir Square with pastoral scenes from postcards, comparing the uprising to a tourist attraction.

“The Break” features two soldiers eating a snack in front of snow-covered mountains, contradicting the images of the protests in Egypt.