A former Islamist guerrilla fighter's plans to enter politics have fanned fears of instability in Algeria, more than two decades after the army halted an expected election victory by his allies and plunged the country into war.

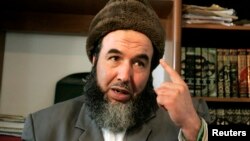

The debate over the new ambitions of Madani Mezrag, who spent the 1990s in the mountains fighting the military before surrendering his rifle in a truce, highlights the uneasy role of Islamist parties in North Africa after the Arab Spring revolts.

Memories of the brutal 1990s war in which 200,000 people died hang heavily over Algeria, whose citizens see turmoil tearing at neighbors Libya, Egypt and Tunisia following the rise of violent Islamist militancy during the Arab Spring.

Mezrag says fears a new Islamist political party will take Algeria back to the bloody years of the civil war are overblown, dismissing any sympathy for jihadist violence and declaring his respect for the state.

"We're not going back to the past. The 1990s are left in history where they belong, but we learned lessons from that time," the bearded firebrand said in an interview at his home in the outskirts of Algiers, wearing a traditional long gown. "We want to turn the page, but not tear the page out."

In Algeria, where the ruling National Liberation Front or FLN party has dominated the political system since independence from France in 1962, the role of political Islam remains a sensitive subject.

Its leadership is going through a delicate time, with aging President Abdelaziz Bouteflika hardly seen since suffering a stroke in 2013, even after winning reelection in 2014 for a fourth term that followed 15 years in power.

A collapse in the global oil price has forced the government to seek ways to make up for lost oil revenues and cut spending, emboldening opposition groups to seek concessions.

Some critics see Mezrag's announcement even helping rally support for the government by evoking the ghosts of the past.

New Crackdown?

Pro-democracy protests that began in Tunisia in 2010 and spread through the Arab world the following year brought long-supressed Islamist parties to power across much of North Africa.

But the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, Justice and Construction Party in Libya and Ennahda in Tunisia have all have been either ousted, defeated or forced by new rounds of protests into compromise with secular rivals.

Mezrag once led the AIS, an armed wing of the Islamic Salvation Front or FIS, the Islamist party that appeared set to win elections in 1992 before the military scrapped the vote, tipping Algeria into a decade of war with armed militants who declared holy jihad on the state.

The conflict soon descended into a brutal war with civilians caught in the middle and the army later accused of abducting thousands of suspects whose families are still searching for them.

In exchange for amnesty in the late 1990s, Mezrag negotiated the surrender of his forces, bringing a partial end to a conflict marked by rural massacres, beheadings and urban bombings known to most Algerians as the "dark years."

He is now proposing to create a political party based on the tenets of FIS, but willing to work within the country's political system instead of against it.

It is early days, and Mezrag's new Islamist movement has not been officially registered. It may not even get that far in a country where most former Islamist fighters are banned from politics under the terms of their national reconciliation.

"We won't permit any person implicated in the national tragedy to create a political party, and we will apply the law with force," Prime Minister Abdelmalek Sellal told parliament this month. "Some benefited from the national reconciliation, but they don't want to live up their obligations."

"Long-term Project"

On his election in 1999, Bouteflika offered an amnesty to rebels who disarmed, provided they were not involved in massacres and bombings in public places.

While AIS came in from the mountains, and worked with the state to convince others to give up arms, more extremist militants kept fighting.

Most former Islamist fighters and FIS members have since been excluded from political life, but they sometimes renew activity, often from overseas exile communities in Europe to dodge the Algerian state.

Mezrag was part of a broad Islamist movement that emerged after an economic crisis forced Algerian authorities to allow limited opposition parties beyond the one-party rule and open up the press in the late 1980s to ease public pressure.

He said new engagement in politics was more about principles than who was in charge.

"It is not just about achieving power," Mezrag said. "It's more about convincing people about your project for society. It's a long-term project."

Those plans have prompted protests among the families of victims of Islamist violence in rural areas most affected during the war. Some victims threatened to march in the capital to resist any Islamist political resurgence.

In a political system observers say is still dominated by FLN elites, opposition parties are often weak and even co-opted or allied silently with government, critics say.

Mezrag himself was invited to the presidential palace as a "national figure" last year to take part in discussions with a top Bouteflika advisor about constitutional reform.

Mohamed Mouloudi, an Algerian expert in political Islam, said Mezrag and other Islamist leaders still believed they represent many Algerians and deserved political recognition.

"Political Islam will not give up its fight to come back politically in Algeria." he said. "When the state is weak like now with oil prices down and security threats over the borders, they do not hesitate to make noise."

Mezrag is coy about the details of his party's political agenda, talking about economic proposals, democracy and saying he respects the state. But he hints at a long term strategy, taking his case to court if needed.

"Sooner or later we will be a political party," he said. "Sooner or later the regime will have no choice but to accept us."