There is more evidence of a large subsurface ocean on Saturn’s moon, Enceladus, according to data gathered by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft.

In a paper published in this week’s edition of Nature, researchers say the intensity of the jets of water ice and organic particles that shoot out from the moon depends on the moon’s proximity to Saturn.

"The jets of Enceladus apparently work like adjustable garden hose nozzles," said Matt Hedman, the paper's lead author and a Cassini team scientist based at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. "The nozzles are almost closed when Enceladus is closer to Saturn and are most open when the moon is farthest away. We think this has to do with how Saturn squeezes and releases the moon with its gravity."

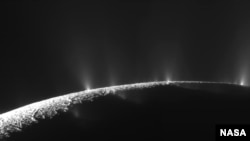

Enceladus’ jets were first seen in 2005 by Cassini. The jets emanate from narrow fissures on the moon’s surface the scientists call “tiger stripes.”

"The way the jets react so responsively to changing stresses on Enceladus suggests they have their origins in a large body of liquid water," said Christophe Sotin, a co-author and Cassini team member at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "Liquid water was key to the development of life on Earth, so these discoveries whet the appetite to know whether life exists everywhere water is present."

The changes in the intensity of the jets were observed using Cassini’s visual and infrared mapping spectrometer. NASA collected more than 200 images of the Enceladus plumes from 2005 to 2012. The data revealed the plumes were dimmest when the moon was closest to Saturn and gradually brightened as the moon moved further away.

Adding the brightness data to previous models of how Saturn squeezes Enceladus, the scientists deduced the stronger gravitational squeeze near the planet reduces the opening of the tiger stripes as well as the amount of material spraying out. They think the relaxing of Saturn's gravity farther away from planet allows the tiger stripes to be more open and for the spray to escape in larger quantities.

In a paper published in this week’s edition of Nature, researchers say the intensity of the jets of water ice and organic particles that shoot out from the moon depends on the moon’s proximity to Saturn.

"The jets of Enceladus apparently work like adjustable garden hose nozzles," said Matt Hedman, the paper's lead author and a Cassini team scientist based at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. "The nozzles are almost closed when Enceladus is closer to Saturn and are most open when the moon is farthest away. We think this has to do with how Saturn squeezes and releases the moon with its gravity."

Enceladus’ jets were first seen in 2005 by Cassini. The jets emanate from narrow fissures on the moon’s surface the scientists call “tiger stripes.”

"The way the jets react so responsively to changing stresses on Enceladus suggests they have their origins in a large body of liquid water," said Christophe Sotin, a co-author and Cassini team member at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "Liquid water was key to the development of life on Earth, so these discoveries whet the appetite to know whether life exists everywhere water is present."

The changes in the intensity of the jets were observed using Cassini’s visual and infrared mapping spectrometer. NASA collected more than 200 images of the Enceladus plumes from 2005 to 2012. The data revealed the plumes were dimmest when the moon was closest to Saturn and gradually brightened as the moon moved further away.

Adding the brightness data to previous models of how Saturn squeezes Enceladus, the scientists deduced the stronger gravitational squeeze near the planet reduces the opening of the tiger stripes as well as the amount of material spraying out. They think the relaxing of Saturn's gravity farther away from planet allows the tiger stripes to be more open and for the spray to escape in larger quantities.