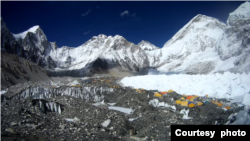

Mount Everest base camp, a sprawling tent village that is home away from home during climbing season for hundreds of aspiring summiteers and support staff, may soon be on the move.

Nepalese officials say they are considering the move to a lower elevation because the Khumbu glacier on which the camp sits is being melted away by climate change, which is undermining its foundation and slowly releasing decades worth of frozen trash and human waste.

But some of the Sherpa climbing guides who make Everest ascents possible are not happy with the idea, arguing that the government should first consider less drastic measures such as limiting the ballooning number of climbing permits, which at around $11,000 apiece have become an important source of revenue for the country.

“I see glaciers vanishing on daily basis. Uncontrollable number of visitors is a problem and it doesn’t make any sense to shift the base camp down,” said Dawa Chhiri Sherpa, 57, who began his career as a cook for a trekking company 35 years ago.

“Consult experts and relevant stakeholders is what should be government doing and not rushing to any decision,” agreed 62-year-old Kay Sherpa, who was born in Scotland and has been living in Nepal since 2009.

He added that the government should try to reduce the influx of helicopters ferrying climbers and other visitors to landing pads at either end of the approximately 22-hectare site to minimize the damage to the ecologically fragile area.

Nepal’s Department of Tourism recommended earlier this summer that a seven-person research group be formed with National Mountaineering Association chairman Nima Nuru Sherpa as its chair. The committee’s mission would be to investigate the present base camp location and potential relocation options.

Taranath Adhikari, director general of the tourism department, said in an interview with the British Broadcasting Corp. that the idea was to move the camp entirely off the fast-receding glacier to a level some 330 meters lower on the mountain.

“It is basically about adapting to the changes we are seeing at the Base Camp, and it has become essential for the sustainability of the mountaineering business itself,” he told the BBC.

The Khumbu glacier has lost the equivalent of 2,000 years of ice in just 30 years, according to research by the 2019 National Geographic and Rolex Perpetual Planet Everest Expedition.

That problem is compounded by the sheer number of visitors to the camp, where more than 1,500 individuals stay for a minimum of two months during the climbing season. Wealthier mountaineers are able to enjoy relatively luxurious accommodations including hot showers, Wi-Fi and catered meals, while acclimatizing to the 5,364-meter altitude.

The proposed move makes sense to Shilshila Acharya, who has played a leading role in efforts to clean up the huge amount of trash that has built up around the base camp since Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay Sherpa first reached the summit in 1953.

“Once the waste is accumulated there, mountain cleanup is very risky and expensive work,” said Acharya, the director of Avni Ventures Pvt Ltd., which is an official recycling partner of Mountain Clean Up Campaign 2021 and 22. Moving the camp would at least temporarily facilitate the clean-up and have safety benefits, she told VOA.

Based on current estimates that the government is spending $1.5 to $2 million a year on the clean-up, “it will take another 50 to 100 years to clean up the existing waste from all mountains,” she said. “So it is going to be costly in the long run if something is not done about it.”

Shafkat Masoodi, a veteran hiker from Kashmir who visited the base camp in 2018, argued that the government must act quickly to move the camp and limit the number of climbing permits issued each season.

“It will prove disastrous in the near future” if they don’t act, he said. “Just imagine the number of climbers per season supported by almost double the number of Sherpas and porters spending at least six months in a year in these glaciers. The garbage and human waste dumped by these is just turning the Khumbu glacier into a polluted river down the mountains.”

But Anja Bagale, operations director at Hotel Himalaya in Kathmandu, pointed out that the current base camp location was selected by experienced Sherpa guides because it is the safest and most practical place from which to launch a final three- to five-day assault on the summit. He argued that the solution is to limit the traffic to the site, not to move it.

Ramesh Bhushal, the Nepal editor of Third Pole and an environment journalist based in Kathmandu, also questioned whether the underlying problems troubling the base camp would be resolved by moving it.

“I don’t see any valid point to shift Everest base camp as it won’t solve any problem as stated and possibly increase problems in [the] future,” he said. “But it is also okay to mull about how to deal with problems that have forced the government to reach into that thought of changing the base camp.”