LONDON —

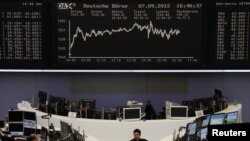

Europe’s central bank made a key announcement Thursday that immediately eased financial pressure on the continent’s troubled economies, lowering interest rates on some of their debts. But the move is controversial, and will not, by itself, solve the continent's economic problems or end speculation about some countries leaving the joint euro currency.

The head of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, announced that the bank will buy bonds issued by Greece, Italy, Spain and other troubled economies. The move is designed to ensure that the interest rates those countries must pay remain reasonable. Private investors were insisting on very high rates in order to buy the bonds, and provide cash for the countries to pay their current bills.

It is a move the bank had refused to make for years, but the chief European economist at London’s Capital Economics, Jennifer McKeown, says it is not enough.

"It’s relatively bold action compared to its previous stance of doing very little," he said. "But I think the fundamental issues for these economies, most notably their lack of competitiveness and the fact that their debt levels are high, are still there.”

The Greek unknown

McKeown’s firm is still predicting that Greece will have to leave the euro this year, and that other countries will likely follow next year.

The underlying economic weakness of the troubled countries is compounded now by years of austerity forced on them by their euro partners as a condition for new loans. McKeown says the strong economies, particularly Germany, are concerned that by easing the pressure, the European Bank’s decision opens the door for the borrowers to violate the austerity agreements.

"There are some real concerns in Germany about the ECB’s actions, over whether the peripheral countries are going to go ahead with their austerity programs," he said.

And there are also concerns about at least two other factors - whether the borrowers can possibly stick to the austerity in the face of long and deep recessions and the resulting public outcry, and whether if they do follow the rules they can turn their economies around in any reasonable timeframe, even ten years.

Hard times ahead

Either way, experts say there is a lot of pain ahead for the troubled countries in the form of recession, falling wages and benefits, and widespread unemployment. And the chief economist at the Center for European Reform, Simon Tilford, says if the stronger countries don’t agree to share that pain, the troubled countries may force them to, by withdrawing from the euro and defaulting on much of their debt.

"This is an argument about money, basically," said Tilford. "Who pays for misallocated capital, profligate borrowers or irresponsible lenders? The only way of addressing this kind of problem is by both sides taking a hit. And so far the full burden of adjustment is being imposed on the debtors. If they continue with this strategy, then ultimately the only way out will be through countries quitting the currency union."

Tilford says the European Central Bank’s decision could be a significant step toward solving the crisis, but only if Germany doesn’t block it, and only if the bond buying program is big enough and lasts long enough. And he says European leaders need to find a way to enable the weak economies to grow, so they can repay their debts and ease the burden on their people.

The head of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, announced that the bank will buy bonds issued by Greece, Italy, Spain and other troubled economies. The move is designed to ensure that the interest rates those countries must pay remain reasonable. Private investors were insisting on very high rates in order to buy the bonds, and provide cash for the countries to pay their current bills.

It is a move the bank had refused to make for years, but the chief European economist at London’s Capital Economics, Jennifer McKeown, says it is not enough.

"It’s relatively bold action compared to its previous stance of doing very little," he said. "But I think the fundamental issues for these economies, most notably their lack of competitiveness and the fact that their debt levels are high, are still there.”

The Greek unknown

McKeown’s firm is still predicting that Greece will have to leave the euro this year, and that other countries will likely follow next year.

The underlying economic weakness of the troubled countries is compounded now by years of austerity forced on them by their euro partners as a condition for new loans. McKeown says the strong economies, particularly Germany, are concerned that by easing the pressure, the European Bank’s decision opens the door for the borrowers to violate the austerity agreements.

"There are some real concerns in Germany about the ECB’s actions, over whether the peripheral countries are going to go ahead with their austerity programs," he said.

And there are also concerns about at least two other factors - whether the borrowers can possibly stick to the austerity in the face of long and deep recessions and the resulting public outcry, and whether if they do follow the rules they can turn their economies around in any reasonable timeframe, even ten years.

Hard times ahead

Either way, experts say there is a lot of pain ahead for the troubled countries in the form of recession, falling wages and benefits, and widespread unemployment. And the chief economist at the Center for European Reform, Simon Tilford, says if the stronger countries don’t agree to share that pain, the troubled countries may force them to, by withdrawing from the euro and defaulting on much of their debt.

"This is an argument about money, basically," said Tilford. "Who pays for misallocated capital, profligate borrowers or irresponsible lenders? The only way of addressing this kind of problem is by both sides taking a hit. And so far the full burden of adjustment is being imposed on the debtors. If they continue with this strategy, then ultimately the only way out will be through countries quitting the currency union."

Tilford says the European Central Bank’s decision could be a significant step toward solving the crisis, but only if Germany doesn’t block it, and only if the bond buying program is big enough and lasts long enough. And he says European leaders need to find a way to enable the weak economies to grow, so they can repay their debts and ease the burden on their people.