For visitors wondering why a tranquil cemetery outside Madrid suddenly needs around-the-clock police security, the answer is simple: an empty burial space awaits the remains of Gen. Francisco Franco, who is being reunited with his wife 44 years after he died.

Weather permitting, the Spanish dictator’s preserved body will be flown Thursday by helicopter to the Franco family’s private chapel in the Mingorrubio cemetery. It’s a discrete site compared to the Valley of the Fallen, a vainglorious mausoleum and basilica that Franco built and where he was buried in 1975. The complex, which is topped by a 152-meter (500-foot) granite cross that can be seen for miles, still remains a National Heritage site.

If fog or heavy winds impede the takeoff, a hearse will ride in motorcade along the 57-kilometer (35-mile) route between the old and new burial places, accompanied by live video. A private Mass will be held in the crypt, attended by only 22 of the dictator’s relatives and a handful of officials.

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez’s interim center-left government has meticulously planned Franco’s exhumation and reburial to be “simple, respectful and discreet but ensuring that the world sees how the dictator is no longer in a state tomb,” said a top Sánchez aide who wasn’t authorized to be identified by name in media reports.

Sánchez fought a tortuous judicial and public relations battle to fulfill the desire of many in Spain who considered the mausoleum an affront to his victims and to the country’s standing as a modern European state.

“No enemy of democracy deserves a place of reverence or institutional respect,” the Socialist leader said, celebrating a ruling last month that paved the way for digging up the dictator’s tomb.

Sánchez and the Socialists are eager to get the exhumation done before Spain holds a general election on Nov. 10. All those at Thursday’s private Mass will be screened for recording devices in an effort to head off anything that could make the dictator a martyr.

Other controversial political figures, such as Dominican Republic dictator Rafael Trujillo, are also buried at the Mingorrubio graveyard. Franco’s body will lie not far from Luis Carrero Blanco, whom he had anointed as his successor, and Carlos Arias Navarro, who eventually took over as the dictatorship’s last prime minister after Basque separatists blew up Carrero Blanco’s car. On Nov. 20, 1975, Arias Navarro announced Franco’s death with a trembling voice, a televised scene seared into the minds of many Spaniards.

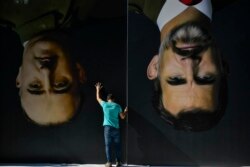

Despite Spain’s democratic progress since then, the Valley of the Fallen is a rarity on European soil, where many traces of past authoritarian regimes have long been erased. Nestled among rocky hills, the cavernous complex both attracts tourists and those nostalgic for Franco’s ultra-Catholic Spanish nationalism.

The dictator now lies surrounded by decrepit graves, most anonymous, of 34,000 people who died during and after the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) that pitched those who backed the democratic Republican government against Franco’s rebellious military Nationalists.

The tomb is seen as an insult by left-wing parties and relatives of his victims. Throughout the country, an estimated 100,000 people remain unidentified and are still buried, often in unmarked mass graves, from the war and the following years of Franco’s regime, despite pressure from relatives’ associations and a Historical Memory Law that in 2007 sought to redress the issue.

Paul Preston, a historian with the London School of Economics, said the move “was long overdue” because such monument “would be unconceivable in Germany.”

“The political consequences of keeping the mausoleum are different in a country where there hasn’t been a process of de-Nazification,” said Preston, an author of a Franco biography.

The autocrat died at 82, outliving most of his European peers, and “oversaw a great brainwashing, or sociological Francoism,” Preston said. “Even with democracy, Spain didn’t go through any ‘de-Francoization’.”

In addition to being the burial site of Franco’s wife, Carmen Polo, the government chose the Mingorrubio cemetery because it’s at the end of a road that passes military and police barracks and is near the palace that Franco once called home. Old hunting grounds surrounding the nearby village still bear the dictator’s mark, and few residents will complain about the return of an old neighbor.

“If they can’t find a place to bury him, I’ll go and dig up the grave of my late husband to lend the Caudillo a space,” said Juanita Pañero as she swept leaves by a house adorned with the Spanish flag. The 91-year-old, whose late husband was a member of Franco’s guard, moved to the Mingorrubio community in the 1960s, as did many others serving at the El Pardo Palace.

Police vehicles guarding the cemetery are the only sign of the impending reburial. Circumspect officers checked visitors’ IDs and zealously followed reporters around the cemetery, while outside the graveyard gun-carrying military cadets doing drills ran past spandex-clad cyclists. Further down, gardeners pruned tree branches.

At the local bar, 68-year-old Ramón Muñoz said most in the community disliked the unwanted attention that Franco’s return is bringing.

“A lot of people here were well treated by the dictatorship. Others have come later, just because the place is just gorgeous,” the retired civil servant said. “We all like how peaceful it is around here.”