The lower house of Russia's parliament, the State Duma, Thursday overwhelmingly passed legislation that would allow the government to label journalists, bloggers, and social media users as foreign agents.

The bill, which still needs approval from the Federation Council, the upper chamber, and President Vladimir Putin’s signature to become law, expands on existing “foreign agent” measures already targeting select foreign media and Russian NGOs.

The laws have been criticized by human rights groups as highly restrictive but lauded by Kremlin loyalists as essential to protect Russian sovereignty.

Under the new expanded version, restrictions would now apply to journalists and individuals working for media organizations designated as foreign agents by Russia’s Justice Ministry.

The new measure would require those who work for suspect media outlets to label any published materials as “made by a foreign agent” and personally submit to regular audits and inspections of their work and finances.

Employees and contractors with Voice of America, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, and several affiliated partner projects — such as Current Time TV — would appear to be prime targets of the new bill.

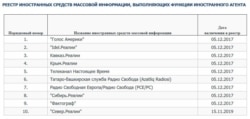

The U.S. government-funded outlets are currently the only media on the Justice Ministry foreign agent media blacklist created in 2017.

Yet, given the vague wording of the measure, the foreign agent label could also be applied to individuals who distribute suspect media content — a move that could have significant implications for Russia’s blogosphere and social media, both of which are largely considered open platforms for political debate.

How Russian authorities would enforce the foreign agent restrictions against individuals is not yet clear.

Political overtones

The bill’s co-author, the chairman of the State Duma's Commission on the Investigation of Foreign Interference in Russia's Internal Affairs, Vasily Piskarev, vigorously defended law as a necessity — citing his commission’s findings that accused several foreign and domestic media outlets of interfering in Russia’s regional fall elections.

That vote was tarnished by the banning of nearly all opposition candidates from participating in the election — prompting a wave of street protests in Moscow through the summer. While foreign and independent media covered the events, Russian state broadcasters largely ignored voters’ frustrations.

“Russian viewers and readers have the right to know of the foreign roots of these media outlets and where they get their money from,” Piskarev said in comments following Thursday’s vote.

“After inclusion on the register, these citizens and media entities can continue their creative activities and continue to publish, provided they fulfill certain conditions,” he added.

Piskarev also insisted Russia was merely introducing measures to mirror those faced by Russian journalists elsewhere — an apparent reference to what Russia says is the harassment of its RT America and the network’s journalists working in the United States.

RT America was forced to register as a foreign agent with the U.S. Justice Department in 2017, a move that prompted similar measures against American government-funded media.

The potential info-chill to come

Rights groups warn the new foreign agents law would cast a much wider chill over Russians’ access to free speech over the airwaves and online.

“The new 'foreign agent' legislation quite simply is intended to silence critical voices and further limit Russian citizens’ right to access information,” said Hugh Williamson, Human Rights Watch's Europe and Central Asia director, in a statement on the organization’s website.

Russia’s daily Kommersant newspaper, a Kremlin-favored publication known for providing light critiques of state policy, noted the vagueness of the law in the face of the Internet sharing culture would mean that nearly “half the country” would risk running afoul of its provisions — including Russians who work in companies with foreign funding or scientists who receive international grants.

Russian foreign agents laws were first introduced in 2012 in an effort to end foreign funding of Russian NGOs, a move that civil society advocates said had echoes of Soviet days when they were likened to potential traitors and spies.

Indeed, Putin argued at the time that foreign-funded NGOs were less interested in developing civil society and more intent on fomenting revolution for their Western donors.

Given the choice to identify themselves as foreign agents or face mounting penalties and court ordered fines, many organizations chose to shutter their doors.

The law’s political overtones have again been apparent of late as authorities have used it as a blunt instrument against perceived enemies at home.

The Justice Ministry last month said it was adding the Anti-Corruption Foundation, an NGO led by opposition leader and Kremlin critic Alexey Navalny, to the foreign agent registry.

The move came after the organization — which has long tortured the Kremlin with a series of anti-corruption investigations into government malfeasance — supported a series of pro-democracy protests over the summer that led to the arrest of over 2,000 demonstrators.

Russia’s officials justified the decision by saying the organization — which exists on crowdfunded donations from Russian citizens — had received two small wire transfers from abroad.

Then, in early November, Russia’s Supreme Court used the law to rule for the dissolution of For Human Rights, an organization with roots in the Soviet dissident movement that was defending the rights of Russians arrested in police sweeps tied to the summer's unrest.

Speaking on the respected Echo of Moscow radio station, the organization's founder, 78-year-old Lev Ponomarev, criticized the proposed additions to the foreign agent laws.

“It is, likely, the latest nail in the coffin for the human rights movement in Russia — since all human rights organizations are financed by foreign foundations,” he said.