Russian President Vladimir Putin signed legislation this week increasing fines and penalties against so-called "foreign agents" working in mass media — part of a broader spate of Russian laws that have targeted foreign media, NGOs, and other perceived enemies at home.

The latest measure strengthens a controversial law signed earlier this month that expanded the foreign agent label beyond media outlets to individuals — making journalists, bloggers and online news consumers potential new targets.

The laws have been criticized by human rights groups as a government weapon to restrict free speech, but are lauded by Kremlin loyalists as essential to protecting Russian sovereignty in the face of what they argue is routine foreign interference.

The foreign agent media law now requires those who work for suspect media outlets to label any published materials as "made by a foreign agent," and personally submit to regular audits and inspections of their work and finances.

Less clear, until now, were the penalties for violations.

Under the new terms approved by Putin, a series of graduated fines takes hold against media companies and their employees.

Initial violations would now mean up to $800 in fines for individuals; $1,600 for management and officials; and up to $16,000 in fines for media companies.

Repeat offenders over the course of a year face even stiffer penalties, including $1,600 in fines or up to 15 days in prison for individuals; $3,200 for management; and $80,000 docked from media companies pending compliance.

With Putin's signature, the law goes into effect Feb. 1, 2020.

The new restrictions appear aimed primarily at journalists and individuals working for media organizations officially designated as foreign agents by Russia's Justice Ministry and Foreign Ministry.

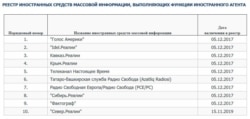

In practice, the law appears to target employees of a small handful of U.S. government-funded media, including Voice of America (VOA), Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) and jointly produced projects such as Current Time TV, which was added to the foreign agents registry in 2017.

At the time, Russian officials said the move was merely a response to the inclusion of the Kremlin's RT America Network on a U.S. foreign agent registry earlier that same year.

Yet critics of the new laws say their concerns go beyond targeting of U.S. media.

Observers note that the law's vague wording puts average Russian citizens who share suspect content online and receive any income from foreign sources at risk of being snared.

The law will "become a strong tool to silence opposition voices," wrote Human Rights Watch in an article expressing concern over the measure in advance of its passage. "Bloggers have an important role in informing public opinion in Russia, and this is an attempt to control this inconvenient source of information."

In recent months, the Russian government has levied a spate of spiraling fines against NGOs and opposition activists under the foreign agent designation.

While some organizations have collapsed from the financial pressure, others have successfully turned to crowdsourcing to pay off fines and continue work.