Hundreds of Holocaust survivors joined dignitaries and representatives from more than 50 countries this week to mark the 75th anniversary of the liberation by Soviet troops of the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camps, where an estimated more than a one million Jewish men, women and children were murdered, many of them gassed.

Among the survivors laying wreaths and batting away tears Monday at the former camp in Poland was 90-year-old Renee Salt, who now lives in north London. The frail great grandmother, who was transported to Auschwitz as a young girl, expressed the same feelings of many of her fellow survivors — this anniversary could well be the last.

“It breaks my heart every time I come back here, but as I say I’m still alive, Hitler is dead and that’s my satisfaction,” she told reporters. “I want to come, give respect to the dead and look around. I probably won’t come any more, so I wanted to come this time. I want to do whatever I can and it’ll probably be the last time I come here,” she said.

Most of the remaining survivors are well into their eighties. Jewish groups worry that when these individuals die, it will be harder to refute Holocaust deniers, who claim that the Nazis’ systematic slaughter of six million Jews in the 1940s never took place, or has been exaggerated. The Holocaust was the most devastating and deliberate genocide in human history.

Firsthand testimony of the horrors of the gas chambers and the death camps, of ghettoes and firing squads, has been important in stripping away the false claims of fascist sympathizers and historical revisionists, who seek, say Jewish leaders and rights campaigners, to legitimize anti-Semitic sentiment by cloaking it in the guise of academic research.

The noted literary critic and essayist George Steiner argued once that the atrocities committed by the Nazis were of such a deliberate, calculated and bestial nature that they transcend any words that could be used to characterize them.

“Auschwitz lies outside of speech as it lies outside of reason,” he wrote. Issue of language, testimony and the Holocaust obsessed Steiner, whose father had the foresight to move the family from Austria to France to escape the Nazis. Steiner once told this reporter that he suffered the "guilt of an escapee."

However inadequate words may be to convey the depth of the human suffering, or to grapple with the evil that gave rise to it, not to say them, not to use language to describe the Holocaust, would lead to the erasure of history, a forgetfulness that fails to mourn and risks repetition, say Holocaust scholars and survivors.

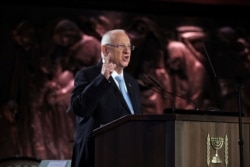

Speaking earlier this week in Jerusalem, Israeli President Reuven Rivlin said, “The Jewish people are a people that remember. We remember not out of a sense of superiority. We remember not so as to dwell in the barbarities of the past or out of a sense of self-righteousness. We remember because we understand that if we don’t remember, history will repeat itself.”

In the fight against anti-Semitism and Nazi nostalgia, the lived experience has been important in proclaiming historical truth and explaining to younger generations what happened in the death camps like Auschwitz, the largest of them all. Salt and other survivors visit schools, universities and parliaments to bear witness and to describe. “

I want people to know what happened,” she said. “I see everything as it happened. I see everything from the day the war started until it finished. I can see everything,” she said.

Various Jewish groups are developing different methods to compensate for the passing of survivors, for the loss of their voices, fearing otherwise not only will the worst genocide in human history disappear into the mists of time, but that with it the taboos against anti-Semitism will weaken even more than many observers fear is already happening.

Dozens of survivors have recorded their memories for the Shoah Foundation at the University of California for use in interactive videos in museums and libraries around the world. Visitors can pose questions and get pre-recorded replies. New social media campaigns fronted by contemporary role models are being designed to try to engage the young.

“For many of my students, these camps are located in a distant place and time,” says Liliane Weissberg, a German and comparative literature professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

“I view it as my task to tell them how present this history is for us today. Auschwitz has marked Germany’s postwar efforts to become a liberal democracy and its current attempts to come to terms with its past; it has defined the history of Israel and the self-understanding of diaspora Jews,” she said.

Remembrance is vital, according to Moshe Kantor, the president of the World Holocaust Forum, because, as the genocide “recedes further into the past, some of its memory is being forgotten.” He worries about the rise in anti-Semitism.

Speaking at commemorations in Jerusalem, he said, “Who could imagine that just 75 years after the Holocaust, Jews would again be afraid to walk the streets of Europe wearing Jewish symbols? Who would have imagined that synagogues would be attacked and cemeteries destroyed and desecrated on a regular basis.”

Recent surveys in Europe suggest that 80% of Jews living in Europe feel unsafe today. Nearly half are considering emigrating and in recent years, 3% have done so annually. “We must educate – about the Holocaust and about the dangers of anti-Semitism, racism and xenophobia, and particularly from an early age,” said Kantor.