Two U.S. advocacy organizations blasted Turkey on Wednesday for stepping up a campaign to crack down on journalists and media outlets suspected of having ties to the plotters of a failed July 15 military coup.

The Committee to Protect Journalists, a media advocacy group in New York, and Freedom House, a research-and-advocacy outfit in Washington, voiced concern about the arrests of more than a dozen Turkish journalists this week and reports late Wednesday that the Turkish government had ordered the closure of dozens of media outlets in the country.

The journalists and media outlets are purported to be associates of Fethullah Gulen, a Muslim cleric living in self-imposed exile in the U.S. who Turkey says masterminded the coup attempt.

“We’re obviously extremely concerned about the developments, particularly against journalists, but this sort of behavior from the government is nothing new,” said Nina Ognianova, Europe and Central Asia program coordinator for CPJ. “For months, the Turkish authorities have gone after journalists who were critical of their policies. It’s escalated now and in the post-coup period.”

State-run and private news outlets in Turkey reported Wednesday that the Turkish government had ordered the closing of 45 newspapers, 23 radio stations, 16 TV channels and three news agencies.

'New dark age'

Nate Schenkkan, Freedom House’s project director for Nations in Transit, a continuing study of democracy in the 29 formerly communist countries in Central Europe and Central Asia, said he was not surprised by the draconian measures and expected more in the next few months.

“We’ve been saying that the crackdown is so serious for so long that it’s hard to find a new way to express it," Schenkkan said in an interview. "It’s a new dark age.”

The reported Turkish government order to shut down media outlets followed the issuance of arrest warrants for 88 journalists this week, including orders for the detention of 47 former executives and senior journalists of Zaman, Turkey’s largest mass circulation newspaper.

Of the 88 journalists wanted, at least 18 have been arrested, according to Ognianova.

Schenkkan added that unofficial lists circulating on pro-government social media sites suggest at least 150 other journalists could be targeted. Many of these may have no ties to Gulen.

Asked about the journalist arrests, State Department spokesman John Kirby reiterated U.S. concern about press freedom in Turkey.

“I think we’d see this as a continuation of ... a troubling trend in Turkey where official bodies, law enforcement and judicial, are being used to discourage legitimate political discourse,” Kirby told reporters. “We’ve been very consistent about that.”

Ongoing detentions

Since the July 15 coup attempt, Turkey has detained more than 13,000 people in the military, judiciary and other institutions. Tens of thousands of other state employees with suspected links to Gulen have been suspended from their jobs in sectors including education, health care, city government and even Turkish Airlines.

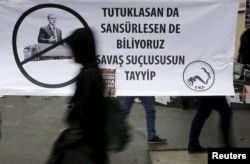

The purges have raised Western concerns that President Recep Tayyip Erdogan may be using the coup attempt to tighten his hold on power.

“I think it’s best understood as a continuation and intensification of a campaign that was already underway,” Schenkkan said of the latest Turkish media assault.

The crackdown on Turkish media dates to December 2013, when pro-Gulen prosecutors launched a massive corruption investigation of the allies of then-Prime Minister Erdogan, triggering a government backlash and journalist arrests.

Since 2013, Freedom House has listed Turkey’s press freedom status as “not free.” Last year, Turkey was given a score of 71 on a scale of 0 to 100, with 100 being the worst.

The score will most likely be lowered further when Freedom House conducts its 2016 global press freedom evaluation.

CPJ branded Turkey the leading jailer of journalists in the world for the second year in a row in 2013. Though Turkey released dozens of journalists the following year under international pressure, it “increased its repressive action against the press,” Ognianova told a House subcommittee hearing on "Turkey’s Democratic Decline” two days before the July 15 coup attempt.

Judicial tools

In reining in the media, Turkish authorities have deployed a ready arsenal of judicial tools, including vaguely worded anti-terror laws and other statutes, to arrest journalists, shut down outlets, co-opt opposition newspapers and impose bans on sensitive reporting topics.

And since last October, the government has effectively taken control of two of the country’s largest media groups — the Koza Ipek Group and Feza Media Group, the owner of Zaman — turning their myriad media organizations into pro-government outlets.

“There has been a systematic persecution that has been going on for months, and that is part of a large crackdown on critical voices in Turkey,” Ognianova said. “Those include journalists who reported on issues such as high-level corruption, the conflict in the southeast between [Kurdish militant group] PKK and security forces, the refugee crisis and the war in Syria."

The media curbs grew so incessant this year that CPJ began publishing a daily summary of press freedom violations in Turkey in March.

Journalists flee

The government’s long arm has cowed media outlets into self-censorship. CPJ has documented that a number of Turkish journalists have simply left the country, while others are trying to flee, Ognianova said without providing details.

CPJ’s Journalist Assistance Program supports journalists forced to go into hiding or relocate to escape threats from local officials and others.

What’s left of an independent media has been co-opted by the government, Schenkkan said.

“Every outlet has been compromised in some way," he said. "Even outlets that might publish occasional criticism still have to find a way to avoid being completely shut down.”

The self-censorship has spilled over into social media, he said. “Lots of people are leaving social media and choosing not to comment.”