The leaders of Eritrea and Ethiopia embraced at Asmara International Airport Sunday, a historic moment in what has long been one of Africa’s most entrenched conflicts.

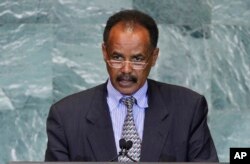

The meeting between Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki and Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed continues a thawing of relations between the two countries.

The summit, in the Eritrean capital, Asmara, is the first time the countries’ heads of government have met since 2000, when Afwerki and former Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi signed the Algiers Agreement, formally ending two years of deadly conflict between the countries.

Cold war

Ethiopia refused to implement the terms of a deal to demarcate the countries’ shared border two years after the Algiers agreement was signed and continued to occupy land awarded to Eritrea by an international court.

That led to a cold war between the East African countries that has lasted nearly 20 years, with particularly damaging effects on Eritrea, a country a fraction the size of Ethiopia.

Afwerki has used the border conflict as a reason for strict rule, compulsory national service and perpetually deferred elections.

But Sheila Keetharuth, the United Nation’s special rapporteur on Eritrea, said these conditions have also led to “arbitrary arrest and incommunicado detention, indefinite military/national service amounting to forced labor, with a range of violations committed in this context, as well as severe restrictions of fundamental freedoms.”

New leader

Eritreans and Ethiopians share language, culture and familial ties. But Eritrea’s 30-year war for independence from Ethiopia, along with the border war, have created deep fissures.

Until recently, the conflict between the countries seemed unsolvable.

That changed in early June, when Ahmed made the surprise announcement that Ethiopia would accept the terms of the Algiers Agreement.

Previous prime ministers have made similar promises, but Ahmed’s overture carried special weight. The 41-year-old assumed office in April at the height of a political crisis after years of unrest in two of Ethiopia’s largest regions. He has since enacted many reforms and promised a new era of unity and accountability.

He is also Ethiopia’s first prime minister from Oromia, a region far removed from the contentious border region and the TPLF political party that controlled Ethiopia since Eritrea, a former province, gained independence in 1993.

In late June, Eritrea sent a high-level delegation to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital, for several days of talks with Ahmed, setting the stage for Sunday’s summit.

Presidential greeting

Afwerki, dressed in an olive-colored suit, embraced Ahmed after he came down the steps from his Ethiopian Airlines jetliner with his entourage and walked across the tarmac.

Red carpet had been laid, and a crowd of onlookers and a brass band flanked the leaders, who later greeted some of those in attendance. Some wore T-shirts adorned with images of the two leaders and told Eri TV, the sole state-owned broadcaster, about the significance of peace between the countries.

Afwerki and Ahmed then rode through Asmara, where cheering crowds warmly greeted them, on their way to begin formal talks.

If the nations do find a path toward peace, the impact could be deep and far reaching.

Ethiopia is landlocked, and access to Eritrea’s ports could transform its economy and strengthen its ability to deliver humanitarian aid. Eritrea’s economy could also benefit, and long-standing human rights concerns could be addressed, observers say.

Keetharuth, who has reached the end of her six-year mandate, told the U.N. that resolving the border conflict would set the stage for peace, but true peace for Eritrea would entail much more.

“The mentality needs to change because up to now it has been a mentality, for both sides, [of] preserving where we are in terms of borders, preserving our gains in terms of territory and preserving other issues.”

Human rights, justice and respect must be achieved for lasting peace, Keetharuth said.