Turkey, once considered the model of an open, secular democracy in the Muslim world, now seems to be stuck in reverse. The government is cracking down on dissidents and erasing the line between religion and state in a country that has served as the bridge between East and West.

Founded nearly a century ago, the overwhelmingly Muslim republic incorporated Western thought and philosophy and focused on science. It became an early member of NATO and aimed for European Union membership.

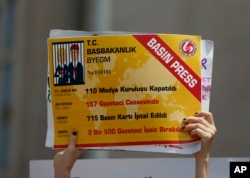

But President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, riding a wave of domestic conservatism, is turning toward increasingly authoritarian rule. The once-vibrant news media have been the target of mass arrests since a failed coup attempt a year ago, with journalists joining opposition legislators in jail on terrorism charges.

Thousands of workers have been culled from the civil service and school system. The education curriculum was revamped to eliminate the theory of evolution from most classrooms. Proposed legislation would allow local religious leaders to register and conduct marriages.

Fears of extremism

Critics inside and outside the country see a steady assault on the secular system, along with marginalization of minorities, which they fear could feed extremism.

“Basically, President Erdoğan is destroying Turkey’s secular education system,” said Soner Cagaptay, Turkey program director at the Washington Institute policy organization. “That is the key reason why Turkey worked as a democratic society, which did not produce violent jihadist radicalization.

“The replacement of secular education with a nonsecular curriculum will inevitably expose Turkey to jihadist recruitment as well as radicalization efforts by groups such as ISIS and al-Qaida, both of which thrive across Turkey’s border in Iraq and Syria.”

The Education Ministry announced July 18 that the new national curriculum dropped the theory of evolution and added the concept of jihad. The ministry said evolution is above the level of students and was not directly relevant. It also said jihad was an element of Islam and had to be taught correctly.

Mustafa Balbay, of the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), questioned the changes.

“We have to look at this issue as a whole,” Balbay said. “If you do that, you will see that new steps by the government will move our students away from science and scientific knowledge. Science is the basis of the modern Turkish republic. An 18-year-old person is old enough to be elected to public office, but you tell him he can’t understand the theory of evolution. It makes no sense.”

But the change mirrors the sentiments of much of Erdogan’s conservative supporters.

“Evolution is monkey theory. I don’t believe in monkey theory. Allah created us,” said Kemal, a cab driver in Erzurum. “In Turkey, we as a society have to become more religious. I support the government’s moves. I am a Muslim. I want our country to produce more religious and more ethical generations.”

Rushed legislation

The proposal to open the marriage system to clerics emerged from the Cabinet Erdoğan installed after a recent referendum. Opposition and women’s rights groups say the changes could open the door to underage marriages and could be used to force Islamic traditions on other religions.

They don’t see the need to rush the legislation through, pointing out there are higher priorities, given that the current civil marriage bureaus aren’t overworked.

“It is not a surprise that the first action undertaken by the Cabinet ... is an initiative that will inflict another blow to secularism,” said Candan Yuceer, deputy chair of parliament’s committee on gender equality and a member of the opposition CHP. “This is not a regulation that emerged out of need, but instead is the government’s arbitrariness.”

Parliament lost much of its clout in the referendum, which despite a clearly split electorate, gave Erdoğan the ability to revamp the judiciary and other government organizations to suit his agenda. More regressive legislation is in the works, and there has been talk of restoring the death penalty, which has drawn protests from Germany and other European nations.

The CHP says it will try to stop the marriage bill in parliament, although opponents are finding themselves off balance in fighting the government’s moves. Last year’s attempted coup has significantly weakened the opposition. The government has shackled most of the media and critics of Erdogan’s more conservative policies find themselves labeled as terrorists.

Reporters Kasim Cindemir in Washington and Yildiz Yazicioglu in Ankara contributed to this report.