Lys Isma was brought to the U.S. illegally as a 9-month-old baby when her parents moved from Haiti. But she says she never felt undocumented.

“I didn’t have memories about living anywhere else,” Isma said.

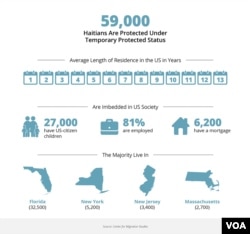

Isma has been receiving protection under the security program known as TPS, or Temporary Protected Status, since she was 15. TPS has allowed Haitians, who were in the U.S., to legally live and work after the 2010 earthquake that devastated the island nation. Almost 60,000 Haitians are TPS holders.

Trump administration ends TPS

But on Monday, the administration of Donald Trump announced that TPS will be ending for Haitians because the U.S. government says Haiti has recovered enough to welcome its citizens back. The government gave Haitian TPS holders until July 2019 to return to Haiti or apply for another kind of legal status.

Isma says she has been “thinking a lot” what would it mean to live in a place she has no memories of.

“I’ve never had to navigate the world as an undocumented adult,” Isma said. “Every time I went to that job interview and they asked for work permit, I’ve had it. Every time I drove, I drove legally with a license. Every time I went past a law enforcement officer, I knew that I had the ability to be here legally present and that’s going to change in a year and a half,” she said.

Isma at 22 is no longer a child, but her story is representative of thousands of children who have Haitian parents in the TPS program. Many, like Isma, were brought to the U.S. from Haiti by their parents. In addition, the Center for Migration Studies estimates that Haitian TPS holders have 27,000 children who were born on U.S. soil.

Toll on children

Stress, fear of losing parents or being forcibly relocated to Haiti while experiencing elevated levels of anxiety can leave long-term impacts, said Lawrence Palinkas, professor of social policy and health at the University of Southern California.

“You will likely see instances of anxiety, depressed aspects, disruption in behavior, and [low] performance in school. There will be a period of stress in terms of the relocation itself. The quality of life Haiti is going to be very different than it has been in the United States,” Palinkas told VOA.

After many years in the U.S., Palinkas said moving away from school, recreation activities, and friends would be a major disruption.

“The separation of those networks and sources of support will undoubtedly be stressful. … That in turn will require a new set of adjustments in addition to an elevated level of stress and strain on the family as they try to cope with both the relocation and residence in Haiti from a very different Haiti than the one which they left,” he said.

When ending TPS, government officials said conditions in Haiti had “significantly improved such that they no longer prevent nationals of Haiti from returning safely.”

But Archange Antoine, executive director of Faith in New Jersey, a faith-based community organization, says the community is nervous and “in total shock” after the announcement.

“You’re talking about a country that’s been through back-to-back natural disasters over the last five to six years, and has been devastated with flooding as well as hurricanes. And a government that is still trying to mobilize and deal with people — still from the earthquake,” Antoine said.

“Right now, we are not taking consideration the real reason of why they were given protection. And we’re making political decisions that are hurting families, and it’s just terrible,” he added.

US born children

For Haitian parents who may be thinking of taking their U.S. citizen children back to Haiti when TPS ends in 18 months, the State Department offers some advice.

A State Department official said in an email to VOA that American embassies and consulates overseas “stand ready to provide appropriate consular services for U.S. citizens.”

The official, speaking on background, said they encourage parents to apply for a passport for their U.S.-born children, before leaving the United States, to document citizenship and identity.

“U.S. citizen children in Haiti will need to have sufficient documentation to meet local authorities’ requirements for access to education and social services. A child’s Haitian citizenship should be documented in order to facilitate such integration,” the official wrote.

State said to refer to the government of Haiti for “more details on what is required to enter school and access health care and other services.”

But Isma, a student who works in a biology genetics lab at her university in Florida, says her community is willing to fight to keep its children in the U.S.

“In my community, we are not the kind of people to break up our families and leave our children behind. … And I know that that is going to be very hard. … [but] they are going to fight to stay here for their kids. And they are not going to have their families separated,” Isma said.