An animal call echoes across the Missouri landscape. It’s the bugle of a male elk, trying to attract a mate - a sound that hasn't been heard in these parts for close to 150 years.

The majestic animals - one of the largest species of deer in the world - haven’t been in the Midwestern state since the mid-1800s, when hunting and habitat loss drove elk in the eastern half of the U.S. to extinction. States from Arkansas to Pennsylvania have since reestablished their elk populations. Missouri is now trying to do the same, athough not everyone is happy about the state’s elk reintroduction plans.

Native wildlife have been successfully re-introduced in other areas - bighorn sheep in Utah, grey wolves in Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, and river otters in New York and Pennsylvania. Missouri’s goal is to bring in 150 elk over the next few years and have the population grow to about 500 animals.

Hopeful news

The small rural town of Eminence sits on the western edge of the elk restoration zone and has already declared itself the "Elk Capital of Missouri." Many of its 600 residents make their living, at least in part, from the tourists who come to canoe down local rivers and hunt deer and turkey. They hope those bugling elk will help give tourism a boost.

"It’s something new, it’s something to see," says resident Billy Dewitt. "It’s something to go out and to enjoy while you’re out in the wilderness."

"We hope it’ll help a little bit in the fall," says Jim Anderson, who owns the Shady Lane Cabins and Motel. "Things die off here after about the middle of October and that’s about when the elk will be doing their thing."

Patty Frazier owns the Hawkins House B&B in Eminence. "I think it’s a great idea. I think it’ll bring more people into the area…Just, put us on the map."

Interlopers?

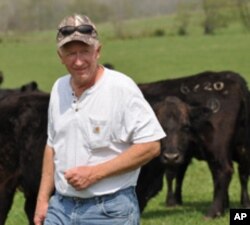

But for some, like cattle rancher Bobby Simpson, elk are dangerous invaders. Simpson’s ranch is about 50 kilometers north of the elk restoration zone. He worries the herd won’t stay put, and that the big animals - which can reach 500 kilos - will cause car accidents, break fences and compete with livestock for forage.

"They’re a lot like cattle in the sense that they graze and they ruminate like cattle," he says. "So their primary diet’s going to be the same thing that our cattle are eating: our good grasses and our good hay fields."

Simpson says he wouldn’t hesitate to shoot an elk to protect his property and livelihood.

"We’re not against elk, and we’re not against wildlife. We just want to protect our way of life, and basically do what we’ve been doing down here for hundreds of years," he says. "And we just don’t need these problems brought onto us unless somebody’s going to be responsible for it. We’re just asking for the state to be responsible for their actions."

According to state officials, they'll be ready to respond to any complaints within 24 hours.

"We’ve developed a protocol to deal with elk that get on properties where they’re not wanted," says Lonnie Hansen, a resource scientist for the Missouri Department of Conservation. "We’d go in with sound cannons or rubber slugs just to basically agitate and push the elk away from the area. Last resorts: trapping and relocating, and possibly shooting but we hope we don’t have to get to that."

The elk released in Missouri will be micro-chipped and fitted with GPS radio collars, so researchers can track their movements and choice of habitats. And in four or five years, once the population gets large enough, the state plans to allow limited hunting outside the restoration zone, to help keep the elk inside its boundaries.

Missouri’s first elk arrived in early May. They’ll have a few months to get used to their new surroundings before the area is opened to the public in July.