Hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans living and working legally in the United States for nearly two decades will know on January 8 whether the U.S. government will allow them to remain in the country under Temporary Protected Status, or face possible deportation.

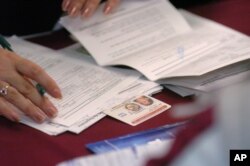

Federal officials grant TPS for citizens of certain countries in cases of extreme hardship - generally natural disasters or war - that make it difficult for immigrants from those nations to safely return. As part of the process, the U.S. government reviews how the situation is changing - and whether it has improved enough to lift the TPS protection. In other words, has the home country recuperated enough that its citizens in the U.S. can go back?

And there is no bigger group among the current TPS countries than El Salvador, with nearly 200,000 beneficiaries and their children.

It is also among the longest-lasting on the list of TPS countries, having received the special status in 2001 after two deadly earthquakes.

WATCH: Nearly 200,000 Salvadorans Anxiously Await Decision on TPS Future

Regular reassessments

The United States has to justify why TPS is extended each time. Most recently, in a July 8, 2016, explanation, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services - the bureau within the Department of Homeland Security that oversees the policy - noted that there “continues to be a substantial, but temporary, disruption of living conditions in El Salvador resulting from a series of earthquakes in 2001.”

That makes the Central American country “unable, temporarily, to handle adequately the return of its nationals,” according to the note in the Federal Register.

The U.S. government cited a slow recovery, due in part to additional natural disasters over the 17 years since the original designation and the deleterious effects on the country’s economy, a resulting housing shortage that has never been rectified; El Salvador’s violent crime rate is also related in part to those economic struggles, according to USCIS. (The agency cited a March 2016 extortion incident in which gangs caused a bottled water shortage.)

El Salvador’s TPS case is unique by sheer volume: 195,000 beneficiaries, who are parents to 192,700 U.S. citizen children. Since TPS does not confer any pathway to citizenship, but does allow people to live and work in the U.S. legally, the longer term cases have created a generation of mixed-status families now facing an uncertain future.

The Salvadorans under TPS are also a part of the U.S. economy. As vice president of business development at Shapiro & Duncan Mechanical Contractors in Rockville, Maryland, Mark Drury has employed Salvadoran workers in a variety of positions, “from the management level down the field level.”

Drury already can’t get the workers he needs. “Right now, we could hire 40 people and not meet the needs we have,” he says. “We have to turn work away every day because there aren’t enough people in the construction industry. To take away more is not a good solution.”

The decision to end TPS

Republican and Democratic administrations have both implemented and ended TPS for some countries. In president Barack Obama’s final months in office, the administration determined that several West African countries placed on the list during the Ebola outbreak had sufficiently recuperated from the pandemic; as a result, thousands of citizens of Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia lost their protection from deportation in May 2017.

In another case, President George W. Bush's administration ended TPS for the Caribbean island of Montserrat in 2005; after eight years, the government determined that since the volcanic eruptions that triggered the status had been ongoing for 20 years, and were likely to continue for decades, the problem "could no longer be considered temporary."

The Trump administration, however, has taken a harder stance on immigration-related issues, including humanitarian policies like TPS. It suspended the program for Nicaraguans, Haitians, and Sudanese and postponed a decision on Hondurans until May. DHS will also have to decide by the end of January about Syria, and later this year about Nepal, Yemen, Somalia, and in 2019, about South Sudan after extending TPS benefits for that country last year.

In the three cases it has already terminated, the Trump administration has given those affected at least 12 months to make arrangements. For some, that will involve trying to obtain immigration status through another pathway; for others, it will mean planning for a return to a country where they haven’t lived for years.

The case of El Salvador

Ending or dramatically reducing TPS has long been favored by groups calling for an overall reduction in foreigners coming to the U.S. Advocates for TPS recipients say Salvadorans - by far the largest group of TPS holders - are so integrated into the U.S. socially and economically that jeopardizing their status here doesn’t make sense.

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, which is active in supporting migrant, immigrant and refugees communities, dispatched a team of clergy and policy staff to El Salvador and Honduras in August to assess conditions for both TPS countries.

“While both El Salvador and Honduras have demonstrated improvements in their existing governmental protection and security efforts,” the delegation noted in a report released in October that “neither nation has the ability at this time to adequately handle the return of its nationals if TPS is not renewed.”

Thursday, almost 400 religious leaders urged Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen in a letter to extend TPS for El Salvador for at least another 18 months “as it currently does not have the infrastructure or institutions to adequately handle the return of its nationals.”

“Terminating TPS for El Salvador would separate families, negatively impact regional security, and have negative economic and humanitarian consequences in El Salvador and the United States. As people of faith, we implore you to think about the moral imperative to love our neighbor, welcome the sojourner, and care for the most vulnerable among us.”

Read this story in Spanish here.