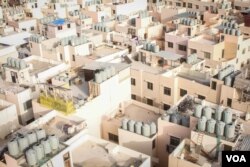

After nearly a decade and more than $200 million in fundraising, landmark efforts to resurrect a Palestinian community destroyed by fighting in northern Lebanon are at a crisis point.

On March 25, as part of a tour of the region, United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon appealed to prospective donors to help complete the reconstruction of the Nahr al-Bared Palestinian camp.

He called for a further $200 million, highlighting the ongoing struggle to restore a once-thriving center for commerce, and rehousing the thousands who remain in limbo amid broken pledges from the international community.

A life from hell

“It is a life from hell,” father of seven Atef Asad Abu Ahmad told VOA. “If I could leave I would, because it’s not humane.”

Ahmad and his family have lived in temporary accommodations within the confines of Nahr al-Bared for the past eight years after fleeing clashes that erupted in the camp in 2007.

The three-month conflict, fought between the Lebanese army and Fatah al-Islam, an al-Qaida inspired group which infiltrated the camp, left Nahr al-Bared in ruins and scattered most of its 30,000 residents.

“People from north Lebanon used to buy goods from here,” recalled Ahmad. “People were comfortable and had work. After the problems, most of our youth are unemployed. Life here has become impossible.”

Over that time, Ahmad has seen new homes rise from the rubble and other people rehoused.

Just like 10,000 others yet to be rehoused, he must wait his turn in desperate conditions.

Meanwhile, the prospect that they will be able return to the place they once lived seems ever more distant.

Inflated costs

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency, or UNRWA, which provides a lifeline to Palestinian refugees, has overseen efforts to rebuild Nahr al-Bared.

When the cleanup operation began, it was hoped that the camp would be rebuilt and 5,000 families rehoused by 2012 at a cost of $277 million.

Things began well. At a conference in 2008, pledges from international donors flooded in, with Western countries and the Gulf states of Saudi Arabia, Qatar, UAE and Kuwait pledging to split the costs.

A vastly complex process, which included clearing more than 12,000 fragments of unexploded ordnance, however, was further complicated by the discovery during the clearance of the ruins of an ancient city, inflating costs to an estimated $345 million.

Since then, $208 million has been raised, with new homes and infrastructure built for 2,200 families.

With Saudi Arabia the only Gulf country to have stuck to its pledge to fund the project, the flood of money coming in has turned to a trickle.

Building sites in the demilitarized camp have grown far quieter in recent months as the displaced look on helplessly.

Acknowledging that with “the region in turmoil,” donors were “hard pressed financially,” said John Whyte, who heads up the rebuilding for UNRWA. He told VOA the need to kickstart funding was “critically urgent.”

It is the biggest project UNRWA has ever undertaken and the first time a Palestinian camp has been rebuilt in Lebanon, he said.

“The project is not just important for this community, but symbolically important to Palestinian refugees across Lebanon and even the wider community.”

Busy with war

With protests on site not uncommon, evidence of frustration at the UNRWA’s perceived inefficiencies and failures is prevalent.

The desperation is further inflamed by the agency being forced to make broader cuts in assistance to the poverty-stricken Palestinian community in Lebanon.

UNRWA, however, is not the only target of frustration. VOA spoke with Palestinians who expressed anger toward Gulf countries they felt have abandoned them.

“They got busy with war and turned their backs on us,” says Ramez al Kateeb.

Kateeb, at least, is relatively content. He recently moved into one of the newly-built homes along with his family.

“We are happy to be back. We have returned to our building; my father and mother live below us and every day get to spend time together.”

The proximity of his relatives is not a coincidence.

The site has been rebuilt with a view to using modern homes to recreate old neighborhoods that themselves reflect the communities that existed in Palestinian areas before their expulsion in 1948 amid the establishment of the state of Israel.

The latest indignity

Whyte insists that a way can, and must, be found to finish rebuilding Nahr al-Bared.

Highlighting visits like that of Ban Ki-moon is crucial in drawing attention to the camp. Whyte said since then, there has been a renewed interest from potential donors in recent weeks.

Others are less optimistic.

Now an elderly lady hobbled by back pain, Eishi Ibraham Ayash spent her childhood in one of the Palestinian villages being rebuilt in Nahr al-Bared.

It was the third time she fled a Palestinian camp in Lebanon amid violence and she too has yet be rehoused - the latest indignity in what she describes as a life “full of hardships.”

“Wherever I have lived, I have not been able to rest,” she told VOA.

“The camp should have been built before. I have little hope for it now.”