Dozens of heavily indebted poor countries around the world were already teetering on the edge of economic catastrophe before the coronavirus pandemic struck early this year. Many were facing staggering foreign debt payments that ate up as much as 40% or more of their governments' annual revenues.

As the world economy slides into an abyss because of COVID-19, those payments could quickly become even more burdensome, making it impossible for many fragile economies to adequately respond to the crisis while meeting their financial obligations.

In the months since the pandemic began, international lenders have taken steps to reduce or postpone debt payments for many poor countries in the near term in order to free up funds for the medical resources that will be needed to fight the virus that so far has infected more than 3 million people and killed nearly 217,000 worldwide.

But debt relief advocates argue that the concessions are insufficient, and in some cases, could leave poor countries in even worse financial condition when the pandemic finally subsides by sharply increasing their debt service in the future and creating further instability.

The situation has given new urgency to calls from activist groups to reduce — or outright cancel — the payments the world's poorest countries owe their creditors.

"This pandemic is an unprecedented shock that requires unprecedented responses," said Tim Jones, head of policy for the Jubilee Debt Campaign, a London-based organization that advocates the cancellation of debt owed by developing countries.

"We are calling for a mechanism to reduce the debts across the board to make the debt sustainable," he said.

Warnings from relief agencies suggest that the consequences of the spreading virus could be particularly dire for countries dealing with war, internal conflict or political instability. A new analysis from the International Rescue Committee found that before the pandemic has run its course, between 500 million and 1 billion people could be infected in dozens of "conflict-affected and fragile countries," resulting in between 1.7 million and 3.2 million deaths.

Deep debt

Something the vast majority of the countries served by the IRC have in common is heavy debt burdens.

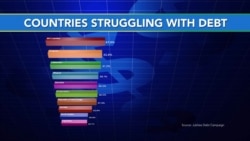

Those countries include Lebanon, which spends about 41% of its revenue on debt service; El Salvador, which spends 38% of its revenues on debt service; and South Sudan, which spends 29%, according to the Jubilee Debt Campaign.

These are not necessarily the most highly indebted poor countries in the world — Sri Lanka pays 48% of its revenue in debt service, and Angola 43%, for example.

But according to the IRC data, Lebanon, El Salvador and South Sudan are among the most at risk of severe coronavirus outbreaks due to complicating factors, including conflict and political instability.

In March, Oxfam America, a global anti-poverty and economic justice organization, began advocating for a $160 billion debt cancellation program to fund preparedness in poor countries around the world.

Achieving any sort of widespread global debt cancellation would require an extraordinary level of coordination between three large sets of creditors: intergovernmental organizations such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund; sovereign nations that have extended credit on a bilateral basis; and private lenders, often represented by large financial institutions or hedge funds.

As a practical matter, it would be simplest for individual governments to cancel bilateral debt, said Georgetown Law Professor Anna Gelpern. It would require policymakers to agree to write off money that taxpayers presumably expected to have repaid.

"That's only as complicated as each of their domestic politics," she said.

China is currently the largest single creditor in the world, with outstanding loans to other countries in excess of 6% of global GDP. A recent study published by the Harvard Business Review found that among the 50 developing countries with the highest levels of debt, about 15% of total obligations were owed to China.

Gelpern, who also serves as a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, said that things get far more complicated when the discussion turns to asking international organizations like the IMF and the World Bank to consider canceling debt. The institutions are capitalized by a large number of countries, including the United States, and would need to persuade their shareholders to agree to the plan.

Agreement would likely entail funding from the member countries to offset at least some of the losses, because organizations like the IMF and World Bank rely on debt payments from borrowers to fund new loans to other countries and would have to severely restrict activities if that income were not replaced.

Persuading private borrowers to cancel debt could be the most difficult proposition of all. In many cases, the obligations are held by institutions — investment funds, for example — that have a legal obligation to act in the interest of their owners. Unilaterally canceling debts could leave the fund managers open to legal action by disaffected investors.

Given the complications, there have been limited steps taken to date to reduce the debt burden on poor countries.

Delaying payments

Responding to a request from the IMF and the World Bank, the G-20 group of the world's largest economies announced on April 15 that they would offer debtor nations the chance to suspend payment on loans for the remainder of the year, which would free up an estimated $12 billion to $14 billion for some 76 of the world's poorest countries.

Following the G-20 announcement, the International Institute of Finance announced that the 450 banks, financial firms and hedge funds that it represents would offer similar relief, totaling about $8 billion.

However, the terms of both the G-20 and IIF plans would require countries to make up the missed payments over a period of four years. That would, at least temporarily, drive their debt service-to-revenue ratios even higher just as they are trying to rebuild in the wake of the pandemic.

IMF grants

The only significant move so far to actually reduce poor countries' debt, rather than just delaying payment, has come from the IMF, which offered 25 countries grants that would cover their debt payments to the fund for the coming six months.

Large-scale debt relief is not completely without precedent. As part of the United Nations' Millennium Development Goals, the Group of Eight major industrialized countries in 2005 proposed that the IMF, the World Bank's International Development Agency and the African Development Fund create a program that would make certain poor countries eligible for 100% cancellation of the agencies' debt claims against them. Over the next several years, 36 countries, mainly in Africa, completed the program and had debt forgiven.

However, less than a decade later, many of those same countries are back near the top of the Jubilee Debt Campaign's list of most indebted countries.