The image has haunted Andrew Brooks for months, but UNICEF’s regional child protection specialist for West Africa described it as if it were yesterday.

An ambulance pulls up to an Ebola treatment unit, and attendants rush a dying woman into an Ebola treatment center. Amid the frenzy, a small, bewildered boy comes into focus.

"Before you even get to find out where the child comes from, the mother dies. The child is left all alone. Suddenly, you have a little boy on your hands," Brooks recalled last week from his base in Dakar, Senegal. He was struck by the situation’s gravity: Decisions made that day could affect the child for the rest of his life.

This particular child happened to be in Monrovia, Liberia, but the scene has played out repeatedly over the past year elsewhere in that country and in Guinea and Sierra Leone. UNICEF, the United Nations Children’s Fund, estimates at least 10,000 youngsters have lost at least one parent or primary caregiver to the current Ebola outbreak that, as of the World Health Organization’s last count, has killed at least 7,588.

The vast majority of children, defined by UNICEF as younger than 18, find homes with relatives or other community members, Brooks and several other regional child welfare experts emphasized.

Testing extended family ties

But a year of battling Ebola — with its devastating sickness, attendant quarantines, disrupted trade and diminished earning power — has strained many households’ ability to absorb more dependents. Add in the very real possibility that a child might carry the dreaded virus, and doors close.

"Families in Africa in a normal situation would take children in two seconds," said Sister Barbara Brillant, a Franciscan Missionary of Mary who leads Liberia’s National Catholic Health Council and its Ebola response. "But right now they’re not. I want to believe the families will take them once the fear has died down or a vaccine is available."

Hundreds of children wind up, at least temporarily, in institutions or group homes where they’re quarantined for up to 21 days while awaiting Ebola testing results or the onset of symptoms. Brooks characterized these settings as "an emergency intervention," noting that workers in the UNICEF-led family tracing and reunification network start trying to identifying kinship or other placements almost immediately.

Other children are less fortunate, winding up begging on the street or exploited for money, labor or sex, the experts acknowledged.

The little boy Brooks saw in Monrovia ultimately had a better outcome, but his case illustrated the challenges involving orphans. Using his mother’s name and the two phone numbers she carried, aid workers eventually were able to track down an aunt who embraced the boy. But first, after he’d tested negative for the virus, he was placed with a welcoming foster mother — an Ebola survivor — who nonetheless couldn’t bring him home. "The community refused to have the boy come," Brooks said.

Countries differ

Circumstances vary not only by child but by country, according to UNICEF representatives.

In Guinea, where the current outbreak began a year ago in the southeastern rain forest, few children apparently have been left homeless. "Existing kinship ties seem to have absorbed children who have lost their parents," Christophe Boulierac, a Geneva-based UNICEF spokesman, told VOA after a recent 10-day tour of the country.

In Sierra Leone and Liberia, where "the epicenter of the disease is in the capitals," more orphans require institutionalized care, Brooks said. He added that years of people flowing to urban centers for employment can weaken familial connections to native communities.

When kinship care is unavailable, aid workers still try to keep youngsters in or near their home communities.

"We don’t want to move them too far," Brooks said. "We really have to recognize and support the resilience of communities who’ve faced hardships. These countries have gone through civil wars, they’ve come through them. They’re not abandoning their children, with the exception of a few."

Care centers as ‘last resort’

Sierra Leone has seven care and observation centers, with 102 young charges among them as of last week, Brooks said. The institutions can hold more, but "we want to ensure that this is understood as a last resort."

Liberia has established an interim care center in Monrovia, with 33 children registered as of last week. Brooks said three more centers are planned in other parts of the country.

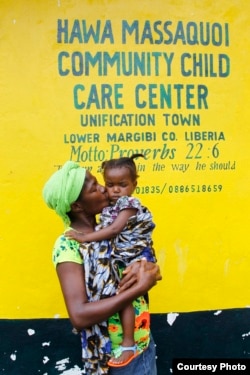

Also in Liberia, the Catholic Church is helping care for "close to 500" orphans, said Brillant, the Franciscan nun. For instance, Consolata Sisters living in Dolo Town – a community about 50 miles east of Monrovia in which more than 100 people died of Ebola – are leading efforts to feed, clothe and otherwise support some 260 orphans living with other residents, she said.

Liberia’s orphans also are receiving support from the Bernardine Franciscan Sisters, a U.S.-based order that just sent a shipping container of food, a spokeswoman said.

"As churches go, most end up taking care of this type of issue, which is what we should be doing," said Brillant, a native of the northeastern U.S. state of Maine who has worked in Liberia for 37 years.

In many centers, including those affiliated with UNICEF, Ebola survivors serve as caregivers, Brooks said.

A survivor has a high level of immunity from infection, he said. Beyond that medical benefit, the survivor understands the isolated or sick child’s plight, he added. "There’s emotional rapport and identification of the experience. There’s also the hope for a child to see someone who’d made it through. It’s an encouragement."

Supporting caregivers

In all three countries, UNICEF, WHO and some other international groups provide incentive packages to assist households taking in youngsters left untethered by Ebola, Brooks said. The aid includes clothes, shoes and time-limited food and cash support for expenses, such as school fees. Follow-up by a social worker aims to help the child adjust to loss and to a new family.

The support system itself is strained and could use help, Brooks added.

"As we invest in targeted support for vulnerable children," he continued, governments, NGO partners and communities should "also invest in the social welfare system. … Let’s strengthen and reinforce our support for children where they are."

Potential for exploitation

While kinship placements usually are desirable, they can carry risk for the children as well as for the households and communities taking them in.

Lucy Steinitz, a protective services adviser for Catholic Relief Services in Sierra Leone, told VOA in an email that aid workers "have heard of many stories where [incentives] were not used to benefit the Ebola-affected child or children. And so children are forced into hard labor, early marriages, or they run away, trading one set of terrible problems for another."

In Bo, Sierra Leone’s second-largest city, children wound up on the street in 10 out of 16 attempted family reunifications, Steinitz said. At the St. George interim care center in Freetown, only two reunifications were completed among 45 children during an eight-week period.

There’s "enormous pressure to trace family members and effect a kinship placement … but it is often very difficult," she said, explaining that relatives face economic pressures and fear the disease’s stigma – or simply may be hard to trace.

UNICEF’s Brooks acknowledged those concerns as "very real."

"It speaks to the need for extremely close follow-up to what we’re doing," he said of child placements. Despite the crisis, "we can’t let kids go to anyone who will have them. We can’t let children become a commodity."