A wave of U.S. and Chinese military activity in the contested South China Sea is making it challenging for the Philippines, at the heart of the maritime dispute, to stick with the neutral foreign policy it has formulated over the past half-decade, analysts say.

The U.S. Navy’s Ronald Reagan Carrier Strike Group “is operating in the South China Sea,” the Navy said on its website June 14. The group is flying aircraft, conducting maritime strike exercises and training for surface-air unit coordination. It calls this voyage part of the Navy’s “routine presence in the Indo-Pacific.”

U.S. officials have said exercises like these – it carried out 10 last year – support Asian allies, including the Philippines, with which the U.S. has had a Mutual Defense Treaty since 1951.

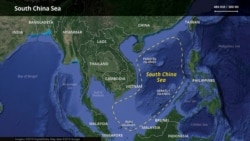

China’s navy, for its part, has increased surveillance on one of its artificial-island military bases in the sea, the U.S. Naval Institute’s USNI News reported June 10. It says a Chinese intelligence-gathering ship and a maritime patrol aircraft, plus one other plane, have appeared at Fiery Cross Reef in the sea’s Spratly Islands, where Manila occupies 10 other features.

The Philippines has fretted for a decade over China’s landfilling of Spratly islets for military use.

In April, Manila sent four of its own navy ships to support coast guard and fishing vessels near an unoccupied Spratly reef where 220 Chinese boats moored in March, domestic media said. A Chinese vessel had sunk a Philippine fishing boat in 2019 and other vessels periodically pressure Filipino fishing operations to leave disputed sea tracts.

“China could slowly expand its maritime presence in the South China Sea using the China Coast Guard, maritime militia and fishing fleet,” said Carl Thayer, Asia-specialized emeritus professor from the University of New South Wales in Australia. China has done this already, he said. “These so-called grey zone operations … were designed to habituate the Philippines to defer to Chinese maritime power because the Philippines was too weak" to fight back, Thayer said.

Brunei, Malaysia, Taiwan and Vietnam also claim parts of the sea, areas that overlap China’s self-proclaimed boundary line. Flare-ups involving the Philippines occur particularly often because of its long coastlines and wide-ranging fishing fleet.

When the U.S. Navy shows up, “it sends reassurances to countries like the Philippines, Singapore, Vietnam, Indonesia about the United States being here in a position where China won’t be allowed to do what it wants to do without any pushback,” said Herman Kraft, a political science professor at University of the Philippines at Diliman.

However, while Manila rejects Beijing’s claims to parts of the South China sea closest to the Philippine archipelago’s west coasts, it hopes to keep receiving Chinese economic help, particularly for infrastructure.

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte has panned U.S. influence over domestic policy, including his deadly anti-drug campaign, while forming an all-new friendship with China since he took office in 2016.

Direct investment from China to the Philippines, a largely impoverished nation trying to fight COVID-19 while boosting infrastructure, came to $140 million last year, 36% more than the amount in 2019, the Chinese Embassy in Manila said.

“Ushering into the new era, President Xi Jinping and President Duterte have met eight times face-to-face, drawing up strategic blueprints for the continuous development of China-Philippine relations,” the embassy said June 9.

Disputes between China and the Philippines in the sea, however, have increased public pressure at home against Duterte’s engagement with Beijing. The Quezon City-based research institution Social Weather Stations found in a survey last July that people’s trust in the United States was "good" but trust was "bad" in China.

China sees friendship with the Philippines as a way to reduce U.S. influence in Asia, scholars have said. China cites old fishing records to back its claim over about 90% of the 3.5 million-square-kilometer waterway that is rich in fisheries and fossil fuel reserves. The United States has no claim.

China’s activity in the Spratly is probably aimed more at resisting the United States than at the Philippines, Kraft said.

“Beijing will surely complain about the USS Ronald Reagan’s sail through the South China Sea, but I suspect that it will be more muted in its disapproval of Manila’s deployments so as not to alienate Filipino voters ahead of next year’s presidential election, much of which could turn on relations with Beijing,” said Sean King, vice president of the Park Strategies political consultancy in New York.

Duterte must leave office next June because of term limits, opening the field to candidates with other foreign policy views.

The Philippines hit another diplomatic crossroads this week when Duterte suspended his decision to cancel a U.S.-Philippine Visiting Forces Agreement. The 1999 pact smooths arms sales and joint exercises. Duterte, once adamant about scrapping it, is looking now for more favorable terms, analysts have said.

“We will have to see what the election renders next year” in the Philippines, said Yun Sun, East Asia Program senior associate at the Stimson Center in Washington. In the United States, she said, “the hope is that Duterte will continue to extend the suspension and the next president will adopt a more rational position on the issue.”