China is bolstering its lead in resource exploration and any conflicts in the South China Sea, a sea disputed by five other governments, by stepping up deployment of expendable, cost-effective drones, analysts believe.

Last month the People’s Liberation Army exhibited an “electronic-warfare variant” of drones that had done just reconnaissance missions before, part of an effort to control information during any military movement, American research organization Center for Strategic & International Studies said.

In September, a drone network operated by the Chinese Ministry of Natural Resources was sent to survey the contested sea’s waters and remote, uninhabited islets, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment said as reported by domestic media. In 2017 Chinese researchers christened a drone specifically for maritime transport and surveillance.

Drones can easily spy because, if caught, operators can claim they’re being used for resource exploration, experts say. Their cheaper than radars and other intelligence-gathering tools, causing little loss if seized, they add.

“The drone is of course a very ideal sort of spy,” said Alan Chong, associate professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore “Drones are in a sense more expendable than aircraft. If they’re shot down, China would raise a protest, but that’s it.”

Stronger position in South China Sea

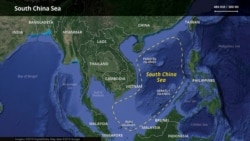

China, hemmed in by other claimant states and monitored by Western powers, isn’t expected to occupy more features in the 3.5-million-square-kilometer sea that’s prized for fisheries and energy reserves.

But drones along with other quasi-military technology will help it find undersea fossil fuels and know quickly if another country is expanding, especially near China’s existing maritime assets, scholars say.

“South China Sea itself is a huge area, (so) that if they want to have a kind of medium range reconnaissance, I think drones are less cost and more efficient,” said Alexander Huang, strategic studies professor at Tamkang University in Taiwan. “In a non-hostile situation, I would say (for) day-to-day operations it’s more cost effective.”

Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam dispute all or part of China’s claims to the sea that stretches from Hong Kong south to Borneo. The U.S. government, sometimes backed by Japan and Australia, passes naval ships into the sea periodically to check China’s activities – to Beijing’s chagrin.

China cites historical records to back up its claims to about 90% of the sea.

Drones: inexpensive and expendable

Drones are traditionally used at sea to check water depths from above the surfaces, take temperature readings and even see how much plankton is in the water, Chong said. Those data help understand marine life and prospects for finding oil or gas.

“If China is using drones, maybe they want to get ahead in knowing what’s the potential of these areas,” said Maria Ela Atienza, political science professor at the University of the Philippines Diliman. “The area is of course very rich in energy resources and other possible economic resources.”

Images captured by drones can be sent instantly to a base station on a tiny sea islet, minimizing losses of information in case they’re captured, Chong said.

China may merge its drones into a plan announced in 2018 to integrate military and civilian activities, Huang said. Military personnel would operate them for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR), he said.

“I don’t know how much scientific implications (a drone program) might carry in such a huge vast area in regards to oceanic research, but it does carry the ISR missions for sure,” he said.

Drone diplomacy

The other claimant states, all militarily weaker than China, fret when China improves its maritime technology.

Vietnam and China got into a standoff earlier this year over energy exploration tracts off the Vietnamese coast, and Filipinos are growing edgier about China’s pressure on their maritime holdings despite friendliness at the state-to-state level.

“People are concerned that China is using technology not only in the South China Sea but spying on the Philippine population in general,” Atienza said. Defense leaders and some legislators are starting to go public with their worries, she added.

China does not disclose details about its drone deployments, but it indicated in June that it sees drones as crucial hardware in the maritime dispute.

The People’s Liberation Army website China.mil then linked a U.S. plan to sell drones in Southeast Asia to containing China. The Pentagon had said that month it would sell 34 ScanEagle drones worth of $47 million to Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam.