U.S. President Joe Biden is keeping pace with his predecessor in the frequency of American warships sent to Asia, analysts believe, a way to get a foothold in contested seas and routinize warnings aimed at the region's strongest maritime force, Beijing.

The guided missile destroyer USS John S. McCain arrived February 5 near the Paracel Islands, a South China Sea archipelago controlled by China but claimed as well by Taiwan, and Vietnam. Brunei, Malaysia and the Philippines vie with China over sovereignty in other parts of the 3.5 million-square-kilometer sea that stretches from Hong Kong to Borneo.

Less than three weeks later, a U.S. Navy destroyer passed through the Taiwan Strait, parts of which are contested by China and Taiwan, as what the navy described as a “commitment to a free and open Indo-Pacific” — often a reference to the adjacent South China Sea. Another navy ship repeated the voyage March 11.

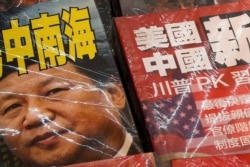

“The Biden administration has inherited most of (U.S. former president Donald) Trump’s political legacy on the South China Sea issue and has not shown much inclination to change it so far,” Beijing’s state-run China Daily news website said on March 18.

Trump’s administration sent navy ships to the South China Sea 10 times in 2019 and another 10 times last year, a U.S. Indo-Pacific Command spokesman said for this report. His administration allowed five in each of the years 2017 and 2018. U.S. officials call the voyages “Freedom of Navigation Operations,” or FONOPs for short.

Administrations before Trump’s would seek approval from the White House and other agencies before sending ships, effectively “politicizing” each move, said Alexander Vuving, a professor at the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies in Hawaii. China would protest each one and follow up with its own military maneuvers in the sea.

“I think the higher frequency of FONOPs also by the Biden Administration reflects the results of a learning process that the United States has undergone in the last several years,” Vuving said. “Lesson number one is don’t make a fuss out of the FONOPs,” he said. “Do not politicize them but normalize them.”

Washington more broadly wants to increase its South China Sea presence, Vuving added, and regular naval operations advance that goal.

Beijing says 90% of the South China Sea falls under its flag and cites historical usage records to support that claim. The six claimants prize the sea for fisheries, undersea fuel reserves and marine shipping lanes.

The United States, China’s former Cold War rival and modern-day superpower rival, makes no claim to the sea. It has stepped in as Beijing takes a military lead in the maritime dispute, threatening a network of pro-U.S. actors such as Taiwan and the Philippines. China particularly alarmed other states before 2017 by landfilling islets to build up military infrastructure.

“FONOPs will become a more institutionalized mechanism, so the U.S. can say that FONOPs is just a regular feature in this part of the world,” said Eduardo Araral, associate professor at the National University of Singapore’s public policy school.

U.S. ships sent to the sea for FONOPs do not make port calls or directly challenge Chinese maritime activity.

Beijing takes a “wait and see” stance now toward the U.S. South China Sea policy, said Huang Chung-ting, assistant research fellow with the Institute for National Defense and Security Research in Taipei. He said it wants to know whether Washington and its allies will differ over how to approach the maritime dispute.

“China under this situation of course will wait and see, then it will attempt to find possible inconsistencies in terms of China policy between the United States and its partners or allies, letting China find a breach,” Huang said.

France, Germany and the United Kingdom, among others, have sent vessels to the South China Sea already this year or made plans to go. Analysts have said they are pushing back against China’s maritime expansion.

Chinese officials say U.S. FONOPs disrupt peace in the sea and violate international law. Just before U.S. and Chinese officials met last week in Anchorage, Alaska, a foreign ministry spokesman from Beijing said China has no “room for compromise on issues concerning its sovereignty, security and core interests.”