Hong Kong’s booksellers and publishers, long known as champions of freedom of expression in the Chinese territory, are now under greater threat following the new National Security Law enacted in July.

Now, booksellers could run afoul of laws that carry strict punishments for vague offenses such as “separating the country” and “subverting state power.”

Hillway Press, an independent publishing house in Hong Kong, has been mainly publishing online novels and textbooks. After last year's anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill movement, it began publishing books on social issues. The publisher said authorities are looking for an excuse to publicly punish someone as an example to others.

"The printing house has received the information that politicians are looking for publishers of political books to kill the chickens to scare the monkeys,” said a Hillway Press executive who requested anonymity and is referred to as Mr. C.

He said the chilling effect had appeared long before the adoption of the national security law. The company’s latest publication, “To Freedom,” which included articles about the anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill movement, was rejected by six printing houses.

The book’s planning and drafting began in April. When the draft was finished at the end of May, China's Communist Party put the Hong Kong version of the national security law on the National People’s Congress Standing Committee's agenda. A long-term printing house partner of the publishing house suddenly changed its mind and declined to print the book because of the sensitive content. Hillway Press had to have the book printed and bound at different companies so it could be published.

"To Freedom" contains many words that criticize the Communist Party of China. To protect interviewees and business partners, the publishing house deleted the sensitive content. "Liberate" has been changed to “free” and “reconstruct." "Anti-CCP" has been taken out. Paragraphs discussing "Hong Kong independence" have been deleted, and illustrations with the words "Liberate Hong Kong" on the cover have been reduced in transparency.

"I am deeply saddened by this self-castration,” said Mr. C. "Under the new legal framework, the publishing industry's biggest concern is where the red line is.”

The blurry legal definition leads to white terror, which leads to fewer social issues that can be explored and, as a result, fewer books that can be published. Mr. C expects Hong Kong's publishing industry to shrink.

"The most frightening thing about the national security law is that there have been no official and clear instructions as to which words and subject matters can be published and which cannot be mentioned. Under such circumstances, we are actually very worried that we will break the law by accident,” he said.

On the fourth day of the legislation becoming law, the Hong Kong Public Library immediately took at least nine political books off its shelves, including the works of Chen Yun, a scholar, Joshua Wong, an activist, and Tanya Chan, a Legislative Council member.

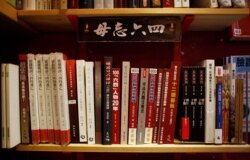

"All along, what best reflected freedom of speech in Hong Kong is our freedom of the press,” said Mr. C. “For a long time, Hong Kong was a place where a hundred flowers bloomed, a hundred schools of thought contended. The books that are banned in Taiwan and mainland China could be bought in Hong Kong. With the national security law, some subjects can no longer be discussed, and some words will not be able to get published.”

Hong Kong Reader Bookstore is an independent bookstore that sells books on humanities and social sciences, with political books accounting for about 30% of the bookstore's sales. Daniel Lee, the store’s director, also said the terrible thing about the national security law was the blurring of the redlines.

"The usual practice in Hong Kong is that as long as the government does not specify what is illegal, we can do it. However, it has always been the practice in the mainland that you do not know that you have broken the law until the moment you are arrested.”

Lee pointed out that there was no clear list of which titles would be officially banned from sale, causing problems for bookstores.

"Maybe until one day when the national security police suddenly show up at the bookstore, we won’t know that a book is forbidden. But we will have already broken the law by accident."

Lee said that when he opened the bookstore, he only wanted to promote Hong Kong's reading culture and never thought that selling books would become a political mission.

"We didn't choose to be on the front line of freedom of speech,” he said. "But in the end, freedom of expression in Hong Kong is endangered, and as bookstores, we have become the reluctant center of this matter.”

Adrianna Zhang contributed to this report.