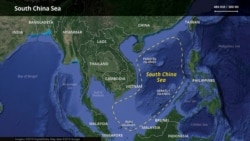

Vietnamese boats fish so far outside their territorial waters that authorities in Malaysia and the Philippines sometimes spot them. Now Vietnamese state agencies are falling in line behind a long-term blueprint that analysts say would increase use of their country’s fishing fleet to assert sovereignty over the South China Sea that is contested by five other governments.

Plans to strengthen fishing by 2030 follow from a resolution passed last year by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Vietnam. The resolution calls for “sustainable development of the maritime economy” and advances toward becoming “a powerful maritime nation”, domestic media outlet VnExpress International reports.

Vietnam’s intentions for the South China Sea surfaced among leaders from 10 Southeast Asian countries this month at an annual summit. Vietnam will chair that bloc, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, in 2020 and have more say-so over its decisions.

Part of the strategy is to develop a “very strong” fishing fleet, said Nguyen Thanh Trung, Center for International Studies director at the University of Social Sciences and Humanities in Ho Chi Minh City. If challenged, officials could say it’s civilian only.

“I would say it’s actually politically smart because, end of day, you are using fishermen to assert your sovereignty to show that ‘I always have a presence there, they are not military personnel, because I don’t think they will wear uniforms at all when they are operating out there,’” said Collin Koh, maritime security research fellow at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore.

Stronger fishing fleet

A law passed 10 years ago got the 2030 process started. It recommended that a self-defense militia escort Vietnamese fishing fleets. Five years later, Vietnam issued a protocol aimed at helping fishermen who build bigger ships as a means of going farther out to sea.

A study by the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore says Vietnamese banks have loaned $176 million to fishermen for upgrades of some 400 ships. More than 10,000 fishermen from one province were given infrared night vision binoculars and firearms.

By 2030, the government will probably establish an agency to carry out the plan and bring in experts to help, Nguyen said. At the moment, he said, officials lack coordination and “specific road maps.” Fuel subsidies for fishing boats are one option, Nguyen said, likewise stronger coast guard protection.

Aquaculture and fishing as well as industry along the 3,500-kilometer Vietnamese coast should see “breakthroughs” by 2030, Vietnam Law & Legal Forum magazine online reported in December 2018. “Fishing activities will be reorganized to reduce onshore fishing, intensify offshore and ocean fishing…and fishing logistics services will be well organized,” the report said.

Cue from China

State-run media reports on the 2030 agenda do not mention a fishing “militia,” but scholars say it will create that outcome. Vietnam’s use of a fishing fleet to protect its maritime claims would follow a lead from China, they say.

“I think that Vietnam’s marine strategy for the most part gets some ideas from what the Chinese government is doing when they are pushing too much power, when they send the fishing vessels south,” Nguyen said.

China’s “maritime militia” has operated since at least 1950, authors Andrew Erickson and Conor Kennedy wrote in a February 2019 study. The People’s Liberation Army showed “early use” of civilian vessels to operate at sea, the paper says.

“Vietnam wants to counter against that in the face of Vietnamese fishermen being chased away from their traditional fishing grounds in the South China Sea,” Nguyen said.

Chinese survey ships and an oil rig also have turned up over the past five years in waters claimed by Vietnam. Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines and Taiwan contest all or parts of the larger 3.5-million-square-kilometer sea that’s rich in fisheries and energy reserves.

Chinese maritime activity angers Vietnam especially because China controls the 130-islet Paracel archipelago that both sides claim. China has consecrated its claims over the past decade by using landfill to build islands. The two countries have sparred since the 1970s over maritime sovereignty.

Risk of arrests

Some Vietnamese fishing boat operators worry the 2030 plan would put them at risk of being rammed at sea by foreign vessels, Nguyen said.

Boats that ply the Sulu Sea controlled by Malaysia and the Philippines also risk arrest, Oh Ei Sun, senior fellow with the Singapore Institute of International Affairs. The Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency has detained a series of Vietnamese boat operators over the past year, including 123 found in May.

Vietnam’s plans to build a fishing militia would show “they really mean business,” Oh said.

“These are Vietnamese fishermen who go all the way to the Sulu Sea and intrude upon the waters of Malaysia and Philippines and so on, so this would be just a formalization and perhaps expansion of what they’ve been doing as well,” he said.